There's no denying that something massive lurks at the heart of the Milky Way galaxy, but a new study asks whether a supermassive black hole is the only possible explanation.

All measurements taken of the galactic center to date are consistent with a highly dense object around 4 million times as massive as the Sun. According to the new paper, though, if you squint just a little, all that evidence can also apply to a giant, compact blob of fermionic dark matter, without an event horizon.

We currently don't have the observational precision to tell the difference between these two models. However, a dark matter composition of the galactic nucleus would give astronomers a new tool for interpreting the dark matter structure of the entire galaxy.

"We are not just replacing the black hole with a dark object; we are proposing that the supermassive central object and the galaxy's dark matter halo are two manifestations of the same, continuous substance," explains astrophysicist Carlos Argüelles of the Institute of Astrophysics La Plata in Argentina.

Dark matter is one of the Universe's biggest mysteries. Scientists can calculate the amount of normal matter in the Universe with great precision. However, once that's all tallied up, there's actually dramatically more gravity than it can account for.

Whatever is responsible for all that extra gravity doesn't absorb or emit light; we only know it exists because of its gravitational influence. That's dark matter. And it's responsible for so much gravity that it makes up roughly 84 percent of the Universe's matter budget.

The way scientists confirmed the presence of and measured the mass of a massive object at the heart of the Milky Way also involved gravity – tracing the long, looping trajectories and changing velocities of high-speed stars orbiting the galactic center.

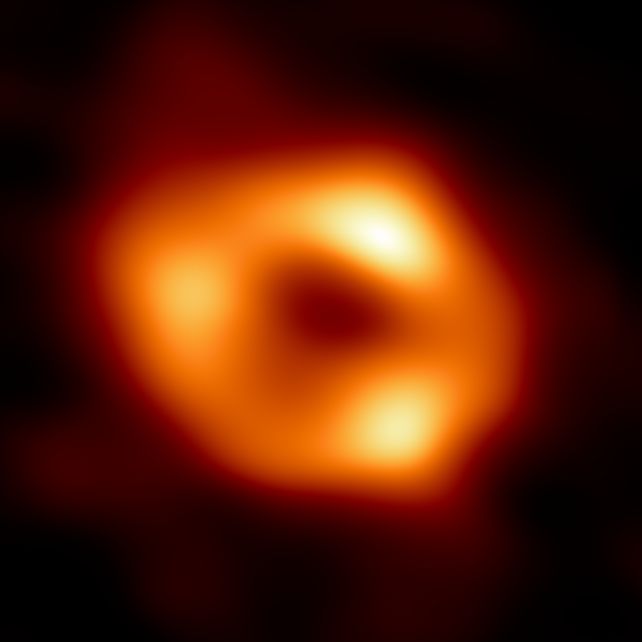

The cleanest explanation for that mass, involving the fewest assumptions, is that it's a supermassive black hole, named Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*). In 2022, an image obtained by the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) collaboration even appeared to show the black hole's 'shadow'.

But it's not the only explanation. For example, previous research showed that an accretion disk blazing around a concentrated blob of dark matter could potentially produce a shadow remarkably similar to the one taken by the EHT.

Led by astrophysicist Valentina Crespi of the Institute of Astrophysics La Plata, an international team wanted to extrapolate this further: could the observed orbits of the stars around Sgr A* also be explained by a dark matter core?

Some models of dark matter are wispy and diffuse, but one candidate allows for dense clumps – fermionic dark matter, particles that obey quantum rules that prevent them from being infinitely squished, similar to the way electrons and neutrons refuse to be mooshed together below a certain density limit.

The theoretical result is an ultradense, gravitationally stable blob similar to a white dwarf or neutron star in principle, but made of dark matter fermions, rather than normal matter particles.

The question then arises, if such an object were sitting in the galactic center, would there be a difference in the way the orbiting stars behave?

There are a number of what we call S stars whose intricate dance around the galactic center traces the gravitational potential of the mass therein. The most important of these tracers is a star called S2, because it has a relatively short 16-year orbit that has been observed and characterized in exquisite detail.

The researchers modeled the behavior of S2, both for a conventional black hole interpretation of Sgr A*, and for their fermionic dark matter blob.

Both models reproduced the star's motion with near-identical accuracy levels. So, this is not telling us that Sgr A* is dark matter; it's telling us that it could be, but we have insufficient data to be able to tell at this point.

However, there's another point in fermionic dark matter's favor. The Gaia spacecraft's map of the Milky Way – the most comprehensive to date – shows that the galaxy's rotation is slowing down at greater distances from the galactic center.

This so-called Keplerian decline is more easily explained by a vast, extended halo of fermionic dark matter enveloping the Milky Way than other dark matter models, the researchers say.

Related: A Star Orbiting a Black Hole Just Confirmed a Prediction Made by General Relativity

"This is the first time a dark matter model has successfully bridged these vastly different scales and various object orbits, including modern rotation curve and central stars data," Argüelles says.

Future observations could help resolve the fascinating question of the true nature of Sgr A*. For example, long-term observations may reveal small characteristics of the stellar orbits that tilt the explanation in one direction or the other. Stars orbiting closer to Sgr A* than S2 may also contain clues.

In addition, future observations with the Event Horizon Telescope may reveal finer details of the light-bending region around Sgr A*. Certain features associated with a black hole's extreme gravity – such as a well-defined photon ring – could be absent or altered if the central object were instead a horizonless dark matter core.

The research has been published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.