Your brain is your body's castle, protected by a near-impenetrable moat known as the blood-brain barrier.

This fortress of boundary cells attempts to keep toxins and pathogens flowing through the rest of your body, away from the sensitive tissues that make life-and-death decisions.

Unfortunately, what makes the barrier so efficient at blocking meddling materials also tends to block medications: a double-edged sword when it comes to treating diseases such as brain cancer.

For years, scientists have been trying to find a way to push drugs past the blood-brain barrier, and in 2014, they unlocked internal access to the first human brain using sound waves.

Now, a clinical trial using the same technique has opened the door wider than ever to let two powerful chemotherapy medications inside the brain.

After treatment, the concentration of cancer-fighting drugs flowing through the neurological tissue of patients was four to six times greater than what could be achieved normally.

A phase 2 clinical trial is already underway to see how all that medicine might impact the health and survival of patients with recurrent glioblastoma, an aggressive and fast-growing form of brain cancer for which there is no cure.

"This is potentially a huge advance for glioblastoma patients," says neurosurgeon Adam Sonabend from Northwestern University.

The phase 1 clinical trial reported here included 17 patients with recurrent glioblastoma, who underwent surgery to have their tumors removed. Whilst in surgery, an ultrasound device developed by a French biotech company was also implanted into their brains.

Every three weeks over the course of two to four months, each emitter released a low-intensity pulse of ultrasound. At the same time, the awake patient received an intravenous injection of microbubbles. The whole procedure took roughly four minutes.

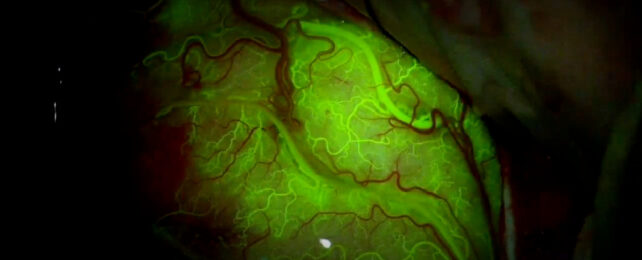

When microbubbles in the bloodstream are struck by a wave of ultrasound they begin to vibrate, allowing them to wiggle through the blood-brain barrier.

After a dose of ultrasound therapy, past animal studies have estimated parts of the blood-brain barrier can stay 'open' for about six hours before they close up.

But this new clinical trial suggests the window of opportunity is even smaller.

The leakiness of the blood-brain barrier is almost completely restored within an hour, Sonabend and colleagues say, which means that medicine needs to be circulating in the bloodstream within that time frame to have any impact.

In the current clinical trial, two different chemotherapy drugs were administered in that critical window: paclitaxel and carboplatin.

Neither drug is typicallly efficient at penetrating the blood-brain barrier, yet both are far more potent therapies than drugs that can cross into the brain and are therefore used to treat brain cancer.

Previous clinical trials have shown that ultrasound therapy is safe and well-tolerated, but this trial is the first to directly show that the procedure results in a significant increase in the concentration of chemotherapy drugs reaching the brain.

With a bigger device, the researchers were able to target a larger part of the blood-brain barrier than previous attempts, though patients reported some transient side effects of the procedure, including headache, limb weakness, and blurred vision, which will need close monitoring in future studies if dosages are dialed up or treatment cycles extended.

"While we have focused on brain cancer (for which there are approximately 30,000 gliomas in the US), this opens the door to investigate novel drug-based treatments for millions of patients who suffer from various brain diseases," says Sonabend.

Gaining access to the brain has long been a medical frontier. Scientists are preparing to storm the castle like never before.

The study was published in the The Lancet Oncology.