As climate change intensifies, South Africa is not only becoming hotter and drier; it's also rising by up to 2 millimeters per year, according to a new study.

Scientists knew this uplift was happening, but the prevailing explanation attributed it to mantle flow within Earth's crust beneath the country.

The new study suggests the uplift is caused by recent droughts and the resulting loss of water, a trend linked to global climate change.

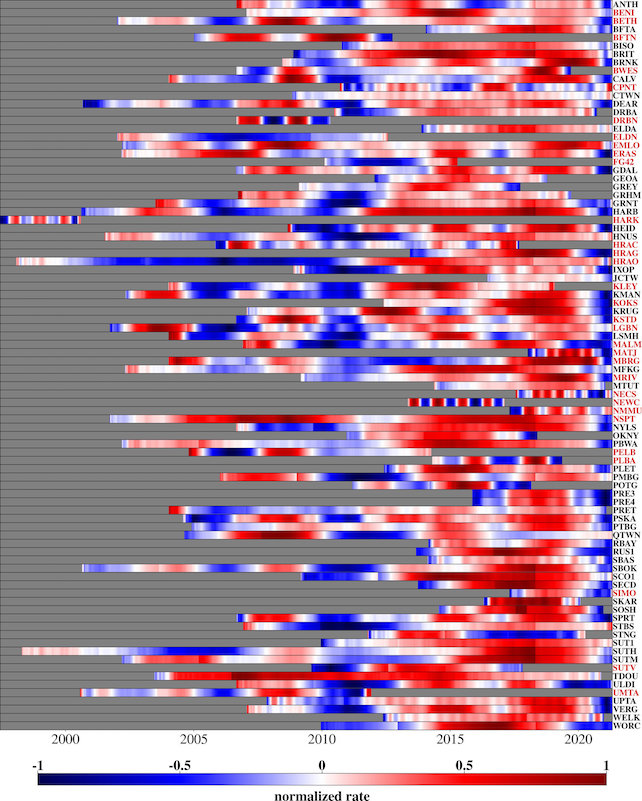

The discovery emerged due to a network of global navigation satellite system (GNSS) stations in South Africa. Mainly used for atmospheric research, this network provides precise data on the height of various sites across the country.

"This data showed an average rise of 6 millimeters between 2012 and 2020," says geodesist Makan Karegar from the University of Bonn.

Experts had ascribed this phenomenon to the Quathlamba hotspot. A localized bulge in Earth's crust could form from the upswelling of material from a suspected mantle plume beneath the region, spurring the recent uplift.

"However, we have now tested another hypothesis," Karegar says. "We believe it is also possible that a loss of groundwater and surface water is responsible for the land uplift."

To explore this possibility, Karegar and his colleagues analyzed the GNSS height data along with precipitation patterns and other hydrological variables across regions of South Africa.

A strong association stood out. Areas where severe droughts have occurred in recent years underwent an especially dramatic uplift of land.

The rise was most pronounced during the 2015–2019 drought, a period when Cape Town faced the looming threat of "day zero" – a day with no water.

The study also looked at data from the GRACE satellite mission, a joint effort by NASA and the German Aerospace Center to measure Earth's gravity field and changes in water distribution.

"These results can be used to calculate, among other things, the change in the total mass of the water storage, including the sum of surface water, soil moisture, and groundwater," says University of Bonn geodesist Christian Mielke. "However, these measurements only have a low spatial resolution of several hundred kilometers."

Despite this low resolution, GRACE satellite data supported the hypothesis: Places with less water mass had higher uplift at nearby GNSS stations.

The team used hydrological models for higher-resolution insight into how droughts can influence the water cycle.

"This data also showed that the land uplift could primarily be explained by drought and the associated loss of water mass," Mielke says.

The researchers suggest that in addition to upward pressure from a mantle plume, the loss of moisture in the crust could also cause it to bulge.

This is another example of the many ways climate change is tweaking the world around us, but it could also offer practical value.

GNSS data, which are cost-effective and simple to collect, could offer a new way to track water scarcity, including critical groundwater resources – widely overexploited by humans for agriculture and other purposes.

Given the dire threat droughts pose in South Africa, as well as many other parts of the world, this finding may provide a valuable window into water availability.

The study was published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth.