Federal health officials took the unusual step on Tuesday of warning the public about an increase in a mysterious and rare condition that mostly affects children and can cause paralysis.

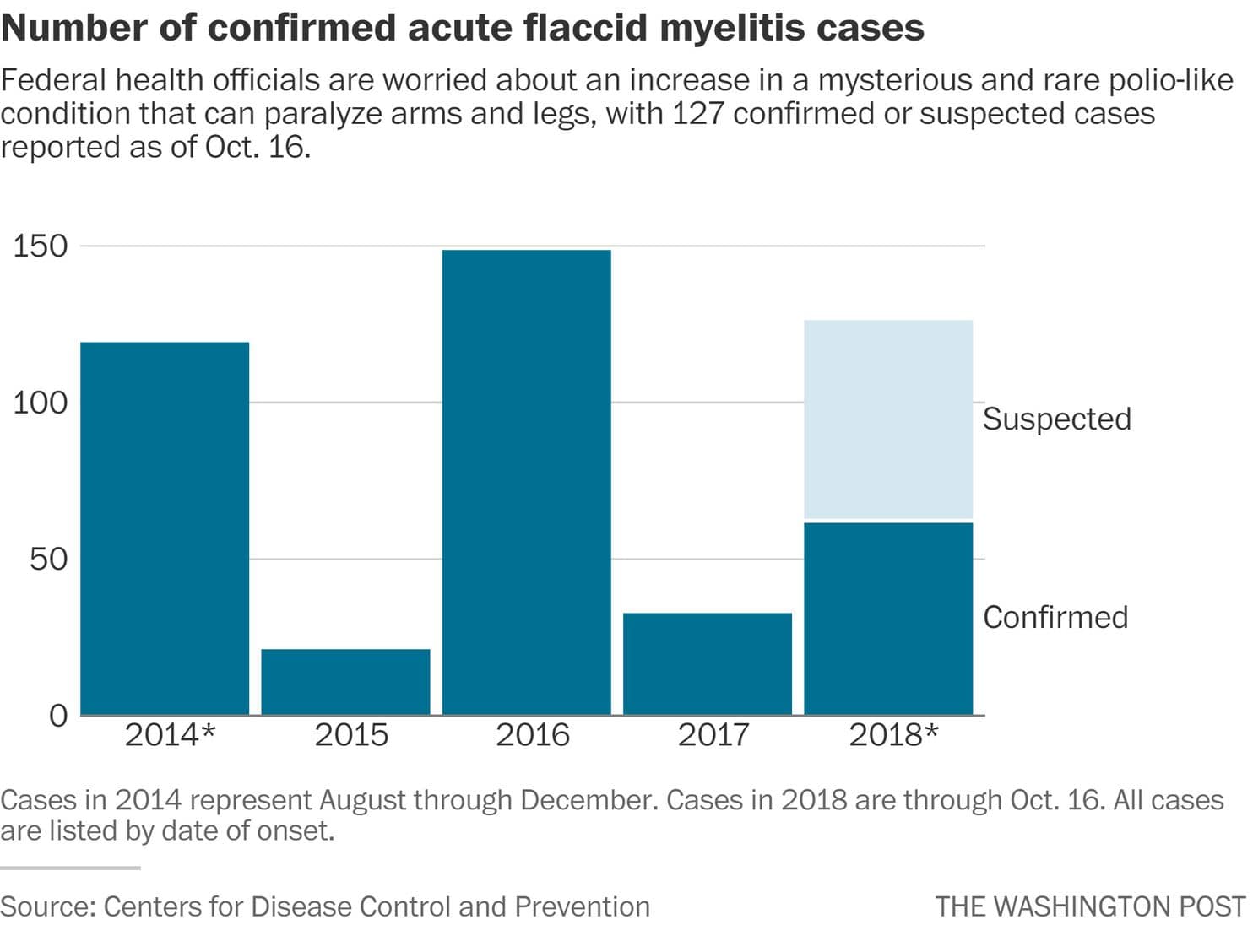

So far this year, 127 confirmed or suspected cases of acute flaccid myelitis, or AFM, have been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention - a significant increase over 2017 and a worrying perpetuation of a disease for which there is little understanding.

Of the cases announced Tuesday, 62 have been confirmed in 22 states, according to Nancy Messonnier, a top official at the CDC. More than 90 percent of the confirmed cases have been in children 18 and younger, with the average age being 4 years old.

The surge has baffled health officials, who on Tuesday announced a change in the way the agency is counting cases.

They also wanted to raise awareness about the condition so parents can seek medical care if their child develops symptoms, and so physicians can quickly relay reports of the potential illness to the CDC.

"We understand that people, particularly parents, are concerned about AFM," said Messonnier, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

Despite extensive laboratory and other testing, CDC has not been able to find the cause for the majority of the cases.

"There is a lot we don't know about AFM, and I am frustrated that despite all of our efforts, we haven't been able to identify the cause of this mystery illness."

The increase in cases appeared to begin in 2014, when the CDC started tracking the illness.

Each year since then, usually in August or September, the CDC has logged a spike in the illness.

The spikes were significantly higher in 2014, 2016 and 2018-to-date than in 2015 or 2017. The CDC knows of one child who died with the disorder in 2017.

Since officials have been unable so far to determine how the disease spreads, they are starting to count suspected cases as well as confirmed to better anticipate increases over the coming months.

It's too early to know whether the total for 2018 will surpass those previous years. But the data reported Tuesday represents "a substantially larger number than in previous months this year," Messonnier said.

There is no specific treatment for the disorder, and long-term outcomes are unknown. The rare but serious disorder affects a person's nervous system, specifically the spinal cord.

Neurological conditions like it have a variety of causes, such as viruses, environmental toxins and genetic disorders.

Among the cases under investigation are five reported to Maryland health officials in recent weeks, a health department spokeswoman said Tuesday. Maryland's first case was reported September 21.

No known cases have been reported in Virginia or the District this year, but there were three confirmed cases in Virginia in 2016, health department officials said.

Messonnier said it was important for parents and clinicians to remember that this is a rare condition, affecting less than one in 1 million children under 18.

"As a parent myself, I understand what it's like to be scared for your child," she said. "Parents need to know that AFM is rare even with the increase in cases we are seeing now."

Still, because this is a "pretty dramatic disease", Messonnier said health officials want to raise awareness about the symptoms to make sure parents seek medical care immediately if their children show a sudden onset of weakness or loss of muscle tone in their arms and legs.

Once diagnosed, some patients have recovered quickly, but some continue to have paralysis and require ongoing care, Messonnier said.

After testing patients' stool specimens, the CDC determined poliovirus is not the cause of the AFM cases. Messonnier said West Nile virus, which had been listed as a possible cause on CDC's website, is also not causing the illnesses.

In some individuals, health officials have determined that the condition was from infection with a type of virus that causes severe respiratory illness.

So far, the CDC has found no relationship between vaccines and children diagnosed with AFM from the 2014 cases.

Officials said they will be conducting additional analysis on this year's cases.

"Our medical team has been reviewing vaccine records when available during this year's investigation and do not see a correlation," said CDC spokeswoman Kristen Nordlund.

The disorder has been diagnosed in unvaccinated children and also in children who have received some of their recommended vaccinations, she said.

The agency doesn't know who may be at higher risk for developing this condition or the reasons they may be at higher risk.

The CDC has tested many different specimens from patients with this condition for a wide variety of pathogens, or germs, that can cause AFM. No pathogen has been consistently detected in the patients' spinal fluid.

Parents can best protect their children from serious diseases by taking prevention steps, such as washing their hands, staying up to date on recommended vaccines and using insect repellent to prevent mosquito bites.

There is no specific treatment for AFM, but neurologists who specialize in treating brain and spinal cord illnesses may recommend certain interventions, such as physical or occupational therapy, on a case-by-case basis.

Benjamin Greenberg, a neurologist who has treated children with AFM at the University of Texas Southwestern in Dallas, said AFM is "exquisitely rare".

But, if their child is diagnosed, parents should prepare for extensive physical therapy - therapy that isn't always covered by insurance, he said. Some children paralyzed by AFM have eventually regained their ability to walk, but need time.

CDC is not releasing a list of the 22 states with confirmed and suspected cases because of privacy issues.

But some state health departments have been making public their reported cases. States are not required to provide this information to CDC, but they have been voluntarily reporting their data.

Dana Hedgpeth and Justin Wm. Moyer contributed to this report.

2018 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.