Spreading your genes through procreation is a biological imperative, and for most animals, this requires, well, staying alive to actually produce babies.

Not so for the wily stick insect! Scientists have now discovered that even if a stick insect is eaten by a bird, it still has a second chance at producing offspring post mortem.

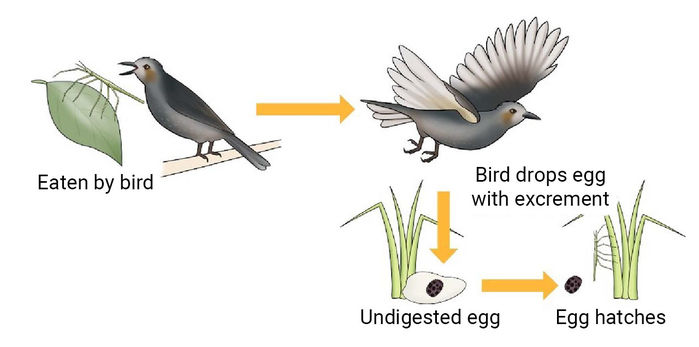

A team led by researchers from Kobe University found that when a stick insect is swallowed by a bird, the hard-shelled eggs nestled within the insect's body can travel through the bird's digestive tract and out the other end without damage.

Warm and cosy within the bird excrement, the eggs may even be able to hatch, birthing a new stick insect far away from its relatives.

(Kobe University)

(Kobe University)

If this sounds familiar, it's because many plants do this with seeds. And now it turns out that stick insects don't just look like plants, they also travel like plants.

Similar to stick insects, plants aren't known for their ability to traverse great distances, which means they have to rely on something else to distribute their seeds.

For many plants, this mean relying on animals, which eat the plant's fruit and then later poop the seeds out intact thanks to their hard shell casing.

The stick insect's bizarre form of gene flow is made possible by another unusual characteristic. Female stick insects are parthenogenic, which means that they can produce viable eggs without the need for fertilisation.

When researchers fed eggs from three species of stick insects to a brown-eared bulbul bird (a common predator), they found between 5 and 20 percent of the eggs were excreted unharmed. Afterwards, one of the insect eggs successfully hatched in the bird excrement.

The researchers note that this may not be the most frequent way stick insects get their eggs to be dispersed, as only a small percentage of the fully developed eggs in a female's stomach would end up intact - but they say it's important for the species nonetheless.

Even if it's not the dominant way for stick insects to spread their genes, it has allowed them to turn death into a remarkable opportunity.

If stick insect eggs are hardy enough to survive a trip through a bird's digestive tract, if they are viable without fertilisation, and if the insect born from these eggs can fend for itself, theoretically, they can be dispersed as far as their predators can fly.

The researchers hypothesise that being eaten by birds is one of the ways that stick insects have so successfully expanded their habitat. By hitching a ride from their avian predators, stick insects have been able to hop across islands and spread to remote corners of the globe.

In fact, stick insects are so ubiquitous, they are currently found on every continent except Antarctica.

"Our next step is analysing the genetic structure of stick insects," said one of the team, biologist Kenji Suetsugu.

"Based on this we'd like to investigate whether similar genetic structure of stick insects can be found along birds' migration flight paths, and whether there are genetic similarities between stick insects and plants that rely on birds for seed distribution."

With this information, the researchers will be able to track how bird dispersal has impacted the distribution and gene flow of stick insects.

The study has been published in the journal Ecology.