In re-examining artifacts from a significant 4,000-year-old Bronze Age burial site near Stonehenge in the UK, archaeologists discovered a toolkit for working with gold objects and coatings that hadn't previously been identified.

The site of the find, the Upton Lovell G2a 'Wessex Culture' burial area, was excavated more than 200 years ago and is crucial in our understanding of Early Bronze Age Britain.

However, what hadn't been spotted before was that some of the unearthed implements had traces of gold on them.

Two bodies were recovered from Upton Lovell G2a, and it now appears that one of them was a goldsmith of some description. This new approach to evaluating the site's contents offers deeper insights into life and work 4,000 years ago.

"This is a really exciting finding for our project," says archaeologist Rachel Crellin from the University of Leicester in the UK.

"At the recent World of Stonehenge exhibition at the British Museum, we know that the public was blown away by the amazing 4,000-year-old goldwork on display."

"What our work has revealed is the humble stone toolkit that was used to make gold objects thousands of years ago."

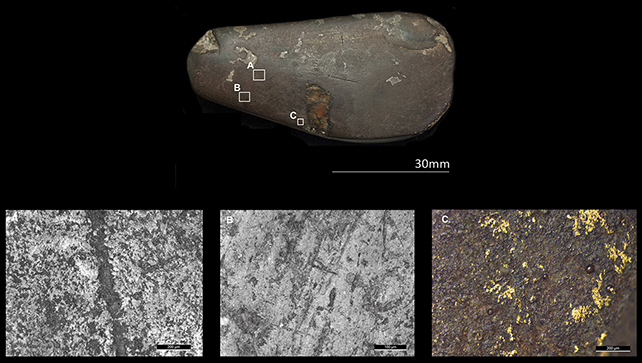

It was a new wear-analysis (a close examination of edges and surfaces) that first revealed gold residues on some of the stone and copper-alloy grave goods. It also became evident that different tools were used for other purposes: not just hammering, for example, but also smoothing out.

Further study with a scanning electron microscope and an energy-dispersive spectrometer – both designed to comprehensively confirm material types – confirmed that the researchers were looking at gold from ancient times.

The team identified gold residues on five different artifacts and spotted an elemental signature in the gold consistent with Bronze Age goldwork found throughout the UK.

These tools were likely used to add gold decoration to objects made from materials such as jet, shale, amber, wood, or copper.

"The man buried at Upton Lovell, close to Stonehenge, was a highly skilled craftsman, who specialized in making gold objects," says Lisa Brown, a curator at the Wiltshire Museum, where the new finds are being exhibited. Brown wasn't directly involved in the research.

"His ceremonial cloak, decorated with pierced animal bones, also hints that he was a spiritual leader and one of the few people in the early Bronze Age who understood the magic of metalworking."

(The researchers note, "The primary burial is usually described as male, although no osteological assessment has been published.")

The team behind this new study is calling for more detailed and nuanced categorization to be applied to archaeological digs such as the one at Upton Lovell G2a – an approach that may reveal plenty more secrets.

It's also important to look carefully at the grave goods buried alongside a person when trying to determine that person's identity and role, the researchers say. That's particularly important when multiple individuals are buried at the same site, as is the case here.

Finally, these artifacts should be considered in relation to each other, the study authors conclude. Here, the establishment of a chaîne opératoire – an 'operational chain' – has revealed something about the distant past that had previously been missed.

"Goldworking tools dating to the Early Bronze Age are extremely rare, so identifying a toolkit for creating composite gold objects is an extremely important discovery," says archaeologist Chris Standish from the University of Southampton in the UK.

"The fact that it is associated with the enigmatic Upton Lovell G2a burial makes it all the more fascinating."

The research has been published in Antiquity.