Images of interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS snapped during the September 7 total lunar eclipse seem to suggest that the latest visitor to the Solar System may be turning green.

That's not all that strange for a comet. Many Solar System comets give off a green glow when they heat up enough to emit vapor. However, for 3I/ATLAS, it might be quite strange: observations of the comet's chemistry obtained to date show very few signs of the dicarbon (C2) molecules usually responsible for a comet's green glow.

This could mean that the C2 is there, but yet to be detected. Or there could be another molecule responsible for making the comet appear green. Either way, the implication is that the chemistry of 3I/ATLAS still has some secrets it is yet to divulge.

Related: Images Show Interstellar Object 3I/ATLAS Is Now Growing a Tail

For the past few days, the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS has been displaying a blue-green gas coma measuring 2.5 arcminutes across. A short tail was also visible on September 9 when photographed with the 12"/f-3.6 astrograph in Namibia. image Gerald Rhemann, Michael Jäger pic.twitter.com/N3rXvYn3N8

— Michael Jäger (@Komet123Jager) September 10, 2025

The images were taken by astrophotographers Gerald Rhemann and Michael Jäger from Namibia during the total lunar eclipse that took place on the night of 7 September 2025.

As a comet grows closer to the Sun, the ices that are bound up around its rocky nucleus begin to sublime, turning into a gas atmosphere, or coma. Molecules in this gas, stimulated by solar radiation, then fluoresce, glowing with light in a range of visible, near-infrared, ultraviolet, and radio wavelengths.

We know from JWST observations that 3I/ATLAS has a peculiar chemical composition that contains larger than usual proportions of carbon dioxide. Other observations so far also show the presence of nickel and cyanogen. But these don't normally make comets emit green fluorescence, and the molecule that does has not been found.

The problem is even thornier than a mere non-detection of C2 might indicate. According to a preprint led by astronomer Luis Salazar Manzano of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, the early detection of cyanogen implies a strong depletion of carbon-chain molecules – including both C2 and C3.

"Our upper limit on the C2-to-CN ratio," they write, "places 3I/ATLAS among the most carbon-chain depleted comets known."

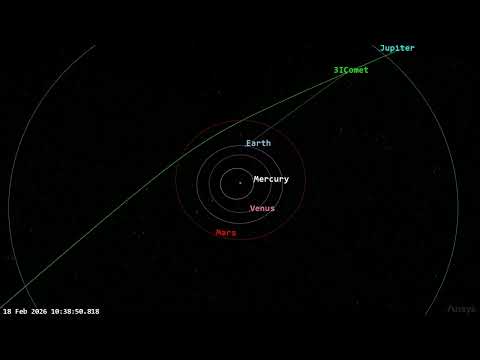

So there's a fascinating mystery there. Here's hoping our scientists can collect enough data to solve it when the comet makes its closest pass to Earth in December.