The notion behind intermittent fasting is simple: eat less for a time, improve your metabolism. The reality is more complex, and a new study finds that some forms of intermittent fasting do not alter markers of metabolic or cardiovascular health.

Researchers, led by a team from the German Institute of Human Nutrition Potsdam-Rehbruecke (DIfE), put 31 women who were overweight or obese on two different intermittent fasting schedules for two weeks each.

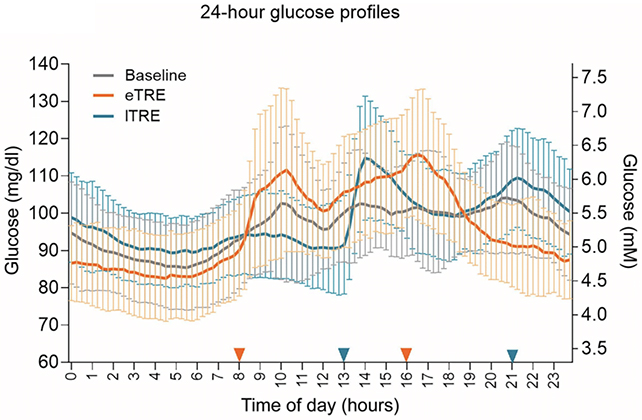

The schedules were 8 am to 4 pm or 1 pm to 9 pm, a particular kind of intermittent fasting known as time-restricted eating (TRE).

While the timing of the schedules differed, the diet parameters were the same: participants could eat like they normally did, and therefore take in the same amount of total calories (making this what's known as an isocaloric study).

Related: A Fasting-Style Diet Seems to Result in Dynamic Changes to Human Brains

Although the women lost some weight, other benefits that might be expected based on previous research – including lower blood sugar levels, lower blood pressure, and lower cholesterol – didn't show up in the data, raising questions about just how effective these timed fasting routines are.

"The beneficial cardiometabolic effects described previously might be induced by TRE-mediated calorie restriction and not by the shortening of the eating window itself," write the researchers in their published paper.

"In this nearly isocaloric trial, no improvements in metabolic parameters were observed after two weeks of TRE."

The findings suggest it may be calorie reduction rather than time-restricted eating itself that boosts key indicators of health inside the body, although it's important to bear in mind this was a relatively small-scale, short-term study.

In addition to the study's modest reductions in body weight, researchers observed changes in participants' body clocks. The timing of their circadian rhythms, including those that nudge the body towards sleep, was shifted based on the TRE schedule.

It's more evidence that our internal clocks can be partially controlled by when we drink and eat, as well as through other triggers (such as when the Sun goes down). This could play into health problems associated with eating late at night, for example.

"Those who want to lose weight or improve their metabolism should pay attention not only to the clock, but also to their energy balance," says biologist and nutritionist Olga Ramich, from the DIfE.

Improving metabolic health is particularly important when tackling insulin resistance and diabetes. Future findings like these may change how diets are structured for people with conditions like these or who are at risk of developing them.

The researchers are keen to continue investigating the relationship between calorie consumption and calorie timing. It's possible that in hypocaloric scenarios (when calories are restricted), timing may have some influence on biological markers of health.

Related: We Were Wrong About Fasting, Massive Review Finds

Various types of intermittent fasting continue to be analyzed by researchers, but studies can differ substantially in terms of the diets that are allowed, the participants, study duration, and the health benefits measured.

"Our findings suggest the importance of calorie restriction for metabolic improvements in TRE," write the researchers.

"Whether the timing of eating under the hypocaloric conditions can additionally contribute to metabolic changes and whether the optimal eating timing differs between individuals warrants investigation in future studies."

The research has been published in Science Translational Medicine.