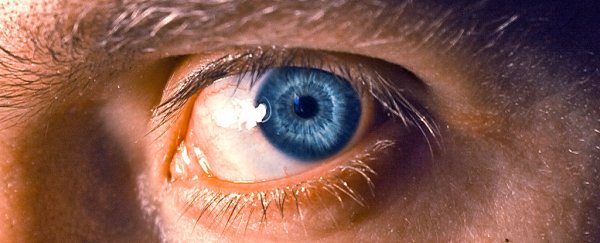

What you can see out of the corner of your eye could be nothing more than an optical illusion powered by your brain, according to a new study.

Scientists have shown that, in some circumstances, our brains fill in the blanks in our peripheral vision, tricking us into thinking we've got as much visual information about what's at the edges of our vision as what's in the centre.

To figure this out, researchers from universities in the Netherlands and the UK set up an experiment to test whether peripheral vision was one of the many optical illusions that can play out inside our minds.

"Our findings show that, under the right circumstances, a large part of the periphery may become a visual illusion," says one of the research team, psychologist Marte Otten from the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands.

"This effect seems to hold for many basic visual features, indicating that this 'filling in' is a general, and fundamental, perceptual mechanism."

The researchers enlisted the help of 20 volunteers who were shown a series of images. In each one, a picture appeared in the centre, which was then gradually joined by a separate picture fading in from the edge.

Participants in the study were asked to click a mouse button when they thought the difference between the two parts of the overall image were the same – when the central picture matched the periphery picture.

The tests showed the volunteers sometimes incorrectly reporting a uniform image ahead of time, before the two pictures matched. It was as if the brain was compensating for the lack of detail in the second image to make it match the first.

"Perhaps our brain fills in what we see when the physical stimulus is not rich enough," suggests Otten.

During the course of the study, the shape, orientation, luminosity, shade, and motion of the images were changed, but this didn't seem to have any effect on the optical illusion.

There was a change when the central and periphery images were more significantly different, though: in these cases, the illusion was less likely to occur, and when it did, it took longer to appear.

Only 20 people were tested in this case, so we need more research to fully understand what's going on. But it opens up some interesting new avenues for research. You can even test out the effects of the illusion yourself here.

In fact, these optical illusions are more common than you might think. Take the Scintillating Grid Illusion, which shows an image featuring 12 black dots – only your brain won't let you see them all at once.

That's because as one neuron becomes more excited and focused, its neighbours become less so. In a way, the brain is trying to get more visual information through the first neuron, even if the others lose out.

Something similar could be happening here, although the researchers haven't got as far as working out why our brains fill in the blanks of our peripheral vision.

"The most surprising is that we found a new class of visual illusions with such a wide breadth, affecting many different types of stimuli and large parts of the visual field," says Otten.

"We hope to use this illusion as a tool to uncover why peripheral vision seems so rich and detailed, and more generally, to understand how the brain creates our visual perceptual experiences."

The research has been published in Psychological Science.