Roughly 76 million years ago, a herd of herbivorous dinosaurs left a trail of footprints that reveals different species may have walked together – and been stalked together, too.

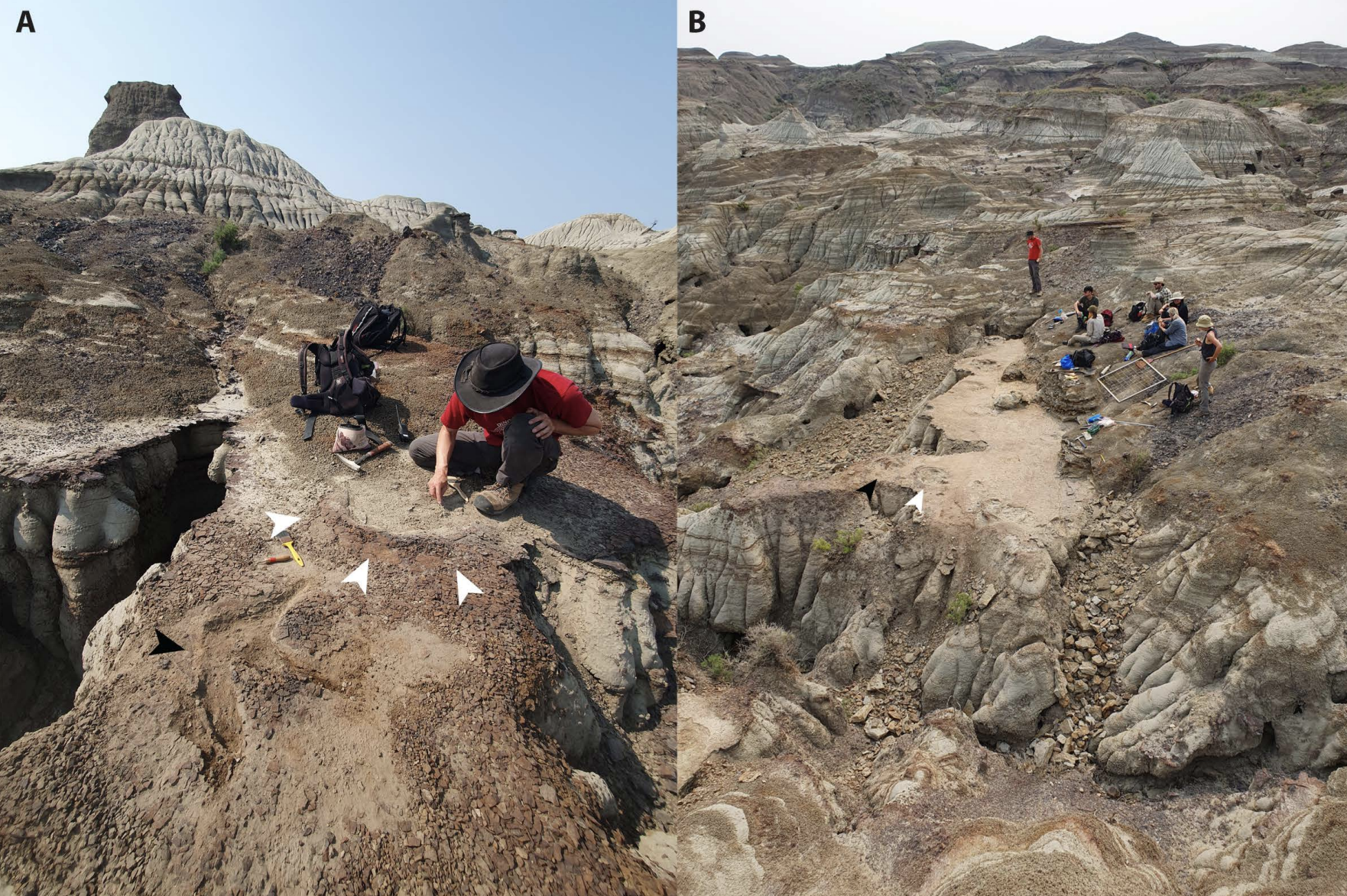

An international team of paleontologists discovered the trackways preserved in ironstone at Canada's Dinosaur Provincial Park. This area is known for its remarkable fossil specimens, but these are the first good set of tracks found in the area.

They reveal something fascinating: tracks from at least five ceratopsian dinosaurs appear alongside those of an ankylosaurid, meaning this could be the first evidence of multi-species herding among dinosaurs.

Related: Ancient Voice Box Finally Reveals How Dinosaurs May Have Sounded

However, while the researchers can confirm these footprints were formed at around the same time, there could be hours or days separating them.

"Ceratopsians have long been suspected to have lived in herds due to the existence of bone beds which preserve multiple individuals of the same species together," says paleontologist Jack Lovegrove from the Natural History Museum in London.

"However, these bone beds only tell us for certain that these animals died together or the bodies accumulated after death. The preserved trackways of several ceratopsians walking together in a group is rare evidence for these animals living together."

The positioning of these footprints suggest the animals were visiting a water source, perhaps following an ancient river. Eerily, other sets of tracks running parallel to the waterline betray predators in the midst: two tyrannosaurs and another small, meat-eating dinosaur, possibly a therapod.

"The tyrannosaur tracks give the sense that they were really eyeing up the herd, which is a pretty chilling thought, but we don't know for certain whether they actually crossed paths," says paleontologist Phil Bell from the University of New England in Australia.

Even if this is more of a montage of cretaceous life, as Lovegrove puts it, it has enabled the researchers to identify many more trackways within the park, which promises much more detail on how these creatures lived alongside each other.

The research was published in PLOS One.