New images from the JWST are about as close as we've ever come to seeing the sky of an alien world outside the Solar System.

Direct images of a gas giant exoplanet orbiting a star called YSES-1 have revealed clouds of fine sand drifting high up in its atmosphere. What's more, similar observations of a neighboring world suggest it is surrounded by a large, swirling disk rich with olivine, a mineral that can form the gemstone peridot here on Earth.

"Everything is exciting about these two results," astrophysicist and lead author Kielan Hoch of the Space Telescope Science Institute told ScienceAlert.

"The observations were novel as we could observe 'two for the price of one' with JWST NIRSpec, and discovering two major planetary features on each object."

Planets outside our Solar System are elusive beasts. They are extremely difficult to see directly; they are very far away, and small and dim, obscured by the blazing light of the stars they orbit.

Of the nearly 6,000 confirmed to date, the vast, vast majority have only been detected and measured indirectly – that is, based on changes their presence evokes in the light of their host stars. Only around 80 exoplanets have been seen directly.

There's a lot you can tell about a planet from the way it tugs on its surrounds or eclipses its star. But direct observations of the light it emits can reveal far more. Even so, it takes a powerful instrument to extract a signal from the faint light of even the closest exoplanets.

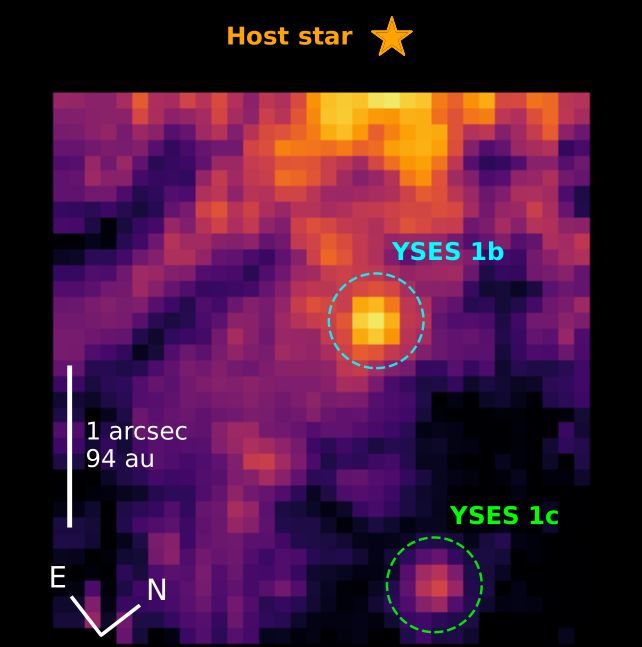

The YSES-1 system is only 306 light-years away and contains two known planets; YSES-1b, which is closer to the star at a distance of 160 astronomical units, and YSES-1c, at 320 astronomical units. YSES-1c is around six times the mass of Jupiter, while YSES-1b is the larger of the two at around 14 times Jupiter's mass, putting it right on the mass boundary between planets and brown dwarfs.

Prior direct observations of this system suggested that the world may have interesting atmospheric properties, but the instruments involved lacked the power to detect them.

Cue JWST.

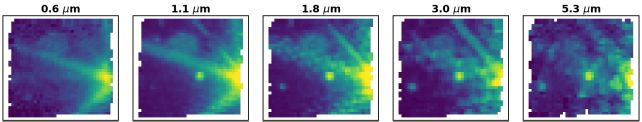

"With the NIRSpec instrument on JWST we are able to get images of the planets at thousands of wavelengths at once. The images can be reduced to produce spectra, which is thermal light coming from the planet itself," Hoch explained.

"As the light passes through the atmosphere of the exoplanet, some of the light will get absorbed by molecules and cause dips in brightness of the planet. This is how we are able to tell what the atmospheres are made of!"

The results? The most detailed spectral dataset of a multi-planet system compiled to date.

Both exoplanets, the researchers found, showed evidence of water, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and methane in their atmospheres – all of which are relatively common atmospheric components. It's where they diverge that things start to get interesting.

"For YSES-1c, we see lots of molecular features from water, carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide, and methane. At longer wavelengths, we see absorption caused by silicate particles, which has a different spectral shape," Hoch said.

"We use laboratory data of different particles and structures to model which silicates fit the data best and determine other properties of those particles. Our models show that there could be small silicate particles high up in the atmosphere that can contain small amounts of iron that rains out of the clouds. However, our models also show that a mixture of only silicates can also fit the data."

No such spectra feature was observed for YSES-1b, but something else emerged: the signature of small grains of olivine in a disk around the exoplanet.

Olivine is a mineral that forms in volcanic conditions here on Earth; particularly fine gemstone-quality examples form peridot. Olivine is also found in meteorites, so it seems the mineral can form easily in molten rock situations.

However, it shouldn't be seen in dust form around YSES-1b. Dust settling is an efficient process expected to take a maximum of about 5 million years, Hoch explained. The YSES-1 system is estimated to be around 16.7 million years old. It's possible that the olivine-rich dust is debris from a collision between objects orbiting near YSES-1b – which means the observations came at a very lucky point in cosmic time.

Both sets of results are spectacular.

"We hoped to detect clouds in YSES-1c's atmosphere as its spectral type is theorized to have a cloudy atmosphere. But, when we saw the feature, it was wildly different from other silicate features seen in brown dwarfs," Hoch said.

"We did NOT expect to see evidence for a disk around the inner planet YSES-1b. That was certainly a surprise."

All the best astrophysical observations raise at least as many questions as they answer. YSES-1 is no exception. The disk around YSES-1b is one big one. We also don't know enough about exoplanetary atmospheres, or how long these objects take to form. Ongoing work to directly study the atmospheres of other exoplanets will help fill in some of these gaps in our knowledge.

"I also am excited about the result as this research was led by early career scientists. I was a graduate student when I proposed to use JWST to image this planetary system, and JWST had not launched yet and was not designed for looking at exoplanets," Hoch said.

"The first five authors of the manuscript range from first year graduate student to postdoctoral fellow. I believe this highlights the need to support early career scientists, and that is a result most exciting for me."

The research has been published in Nature.