Stores of glucose in the brain could play a much more significant role in the pathological degeneration of neurons than scientists realized, opening the way to new treatments for conditions like Alzheimer's disease.

Alzheimer's is a tauopathy; a condition characterized by harmful build-ups of tau proteins inside neurons. It's not clear, however, if these build-ups are a cause or a consequence of the disease. A new study now adds important detail by revealing significant interactions between tau and glucose in its stored form of glycogen.

Led by a team from the Buck Institute for Research on Aging in the US, the research sheds new light on the functions of glycogen in the brain. Before now, it's only been regarded as an energy backup for the liver and the muscles.

"This new study challenges that view, and it does so with striking implications," says molecular biologist Pankaj Kapahi, from the Buck Institute. "Stored glycogen doesn't just sit there in the brain, it is involved in pathology."

Related: Insulin Isn't Just Made by The Pancreas. Here's Another Location Few Know About.

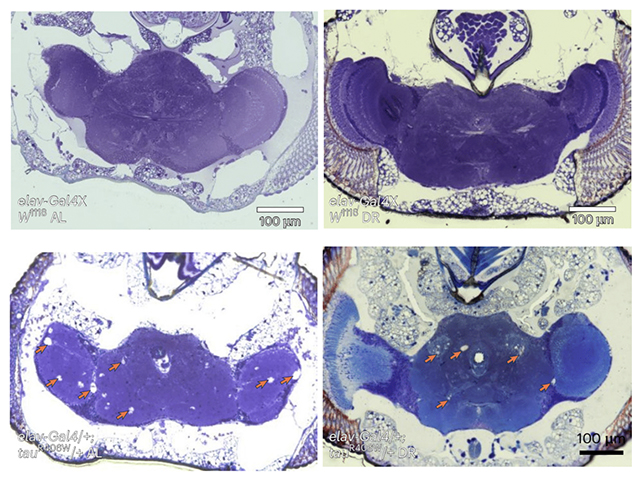

Building on links previously found between glycogen and neurodegeneration, the researchers spotted evidence of excessive glycogen levels both in tauopathy models created in fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) and in the brain cells of people with Alzheimer's.

Further analysis revealed a key mechanism at play: tau proteins interrupt the normal breakdown and use of glycogen in the brain, adding to the dangerous build-up of both tau and glycogen, as well as lowering protective neuron defense barriers.

Crucial to this interaction is the activity of glycogen phosphorylase or GlyP, the main enzyme tasked with turning glycogen into a fuel the body can use. When the researchers boosted GlyP production in fruit flies, glycogen stores were utilized once more, helping to fight back against cell damage.

"By increasing GlyP activity, the brain cells could better detoxify harmful reactive oxygen species, thereby reducing damage and even extending the lifespan of tauopathy model flies," says Buck Institute biologist Sudipta Bar.

The team wondered if a restricted diet – already associated with better brain health – would help. When fruit flies affected by tauopathy were put on a low-protein diet, they lived longer and showed reduced brain damage, suggesting that the metabolic shift prompted by dieting can help boost GlyP.

It's a notable set of findings, not least because it suggests a way that glycogen and tau aggregation could be tackled in the brain. The researchers also developed a drug based around the 8-Br-cAMP molecule to mimic the effects of dietary restriction, which had similar effects on flies in experiments.

The work might even tie into research involving GLP-1 receptor agonists such as Ozempic, designed to manage diabetes and reduce weight, but also now showing promise for protecting against dementia. That might be because these drugs interact with one of glycogen's pathways, the researchers suggest.

"By discovering how neurons manage sugar, we may have unearthed a novel therapeutic strategy: one that targets the cell's inner chemistry to fight age-related decline," says Kapahi.

"As we continue to age as a society, findings like these offer hope that better understanding – and perhaps rebalancing – our brain's hidden sugar code could unlock powerful tools for combating dementia."

The research has been published in Nature Metabolism.