Some people's immune systems may have a head start in fighting the coronavirus, recent research suggested.

A study published last month in the journal Cell showed that some people who have never been exposed to the coronavirus have helper T cells that are capable of recognising and responding to it.

The likeliest explanation for the surprising finding, according to the researchers, is a phenomenon called cross-reactivity: when helper T cells developed in response to another virus react to a similar but previously unknown pathogen.

In this case, those T cells may be left over from people's previous exposure to a different coronavirus – likely one of the four that cause common colds.

"You're starting with a little bit of an advantage – a head start in the arms race between the virus that wants to reproduce and the immune system wanting to eliminate it," Alessandro Sette, one of the study's coauthors, told Business Insider.

He added that cross-reactive helper T cells could "help generate a faster, stronger immune response."

An immunological 'head start'

For its study, Sette's team examined the immune systems of 20 people who got the coronavirus and recovered, as well as blood samples from 20 people that had been collected between 2015 and 2018 (meaning there was no chance those people had been exposed to the new coronavirus).

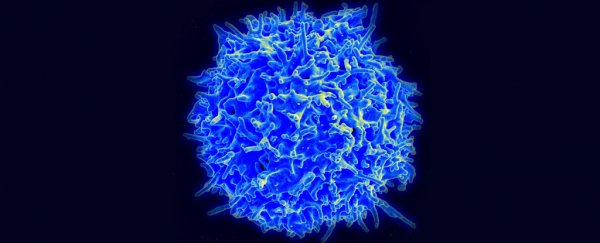

Among the 20 people whose blood samples were taken before the pandemic, 50 percent had a type of white blood cell called CD4+ – T cells that help the immune system create antibodies – that the researchers found to be capable of recognising the new coronavirus and prompting the immune system to fight back right away.

More research is needed to know whether or to what degree this cross-reactivity influences the severity of a case.

"It is too early to conclude that cross-reactivity with cold coronaviruses plays a role in the mild or severe clinical outcome of COVID-19 or the degree of infection in the populations," Maillère Bernard, a scientist at CEA/Université de Paris-Saclay in France who was not involved in the study, told Business Insider.

Evidence for immunity

Among the group of coronavirus patients studied in the new research, only two had severe cases; the other 90 percent had either mild or moderate infections.

The group was selected that way so that the researchers could measure immune responses in average COVID-19 patients, not hospitalized people. (An estimated 20 percent of coronaviruses cases are severe.)

"If you're looking at the exception rather than rule, it's hard to know what's going on," Crotty said. "If the average immune response looked terrible, it would be a big red flag."

The researchers searched the patients' blood for two types of white blood cells: CD4+ cells and CD8+ cells, which are killer T cells that attack virus-infected cells.

The results showed that during the course of their infections, all 20 patients made antibodies and helper T cells capable of recognising the coronavirus and responding accordingly, and 70 percent made killer T cells.

This suggests the body will be able to identify and defend itself against the coronavirus in the future.

"Obviously we cannot tell you with a straight face what will happen 15 years from now because the virus has only been around for a few months. So nobody knows whether this immune response is long-lived or not," Sette said.

But he thinks there's reason for optimism, especially for patients who had severe cases.

"The immune memory is related to the event. If it's a strong event, you'll have a strong memory," Sette added.

"If you almost got run over by a truck, you'll remember it, but you may not remember the colour of the socks you wore yesterday because it's not a big deal."

Yuan Tian, a scientist at the Fred Hutch Institute in Seattle who was not involved in the research, told Business Insider that to learn more about how T cells relate to immunity, "it'd be interesting to study people with severe disease and compare the T-cell response between them and those with mild disease."

That's next on the docket, according to Crotty.

"We're looking to identify T-cell response in the critically hospitalized," he said. "It's being done as we speak."

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: