This article was written by Simon Graff from Aarhus University, and was originally published by The Conversation.

For decades, medicine has recognised the powerful way grief can influence the heart. It's been called Broken Heart syndrome or Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, and evidence that severely stressful life events increase the risk of acute cardiovascular incidence, like a heart attack, continues to grow.

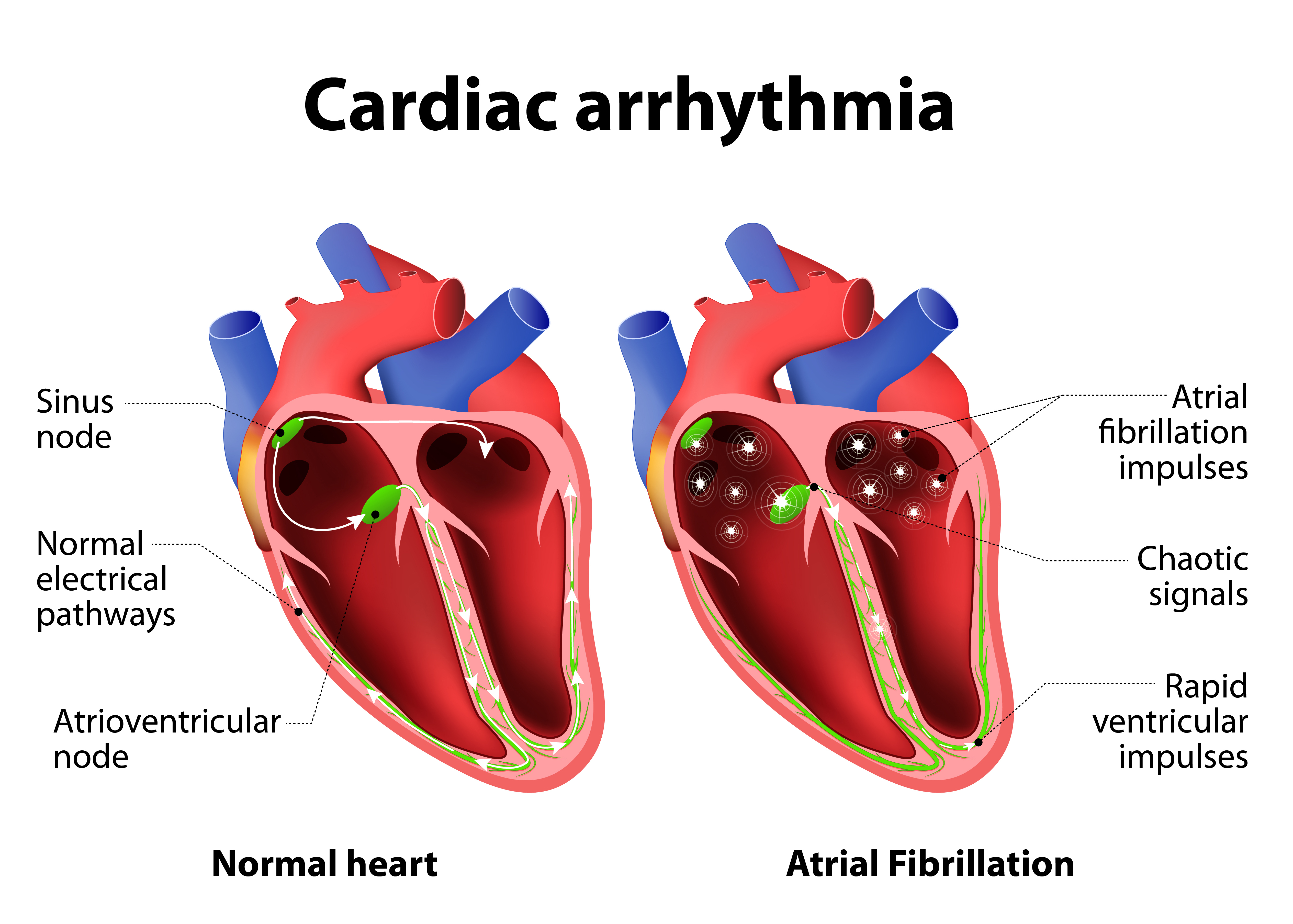

Meanwhile, anecdotal reports and case studies have long described the relationship between acute stress and the development of an irregular heartbeat, known as cardiac arrhythmia.

The most common form of cardiac arrhythmia in the western world is atrial fibrillation, where the heart beats improperly (usually more rapidly) and irregularly. But, so far, no large studies had examined the link between stressful life events and atrial fibrillation.

Our study, conducted at Aarhus University and published in the journal Open Heart this week, was based on data from nearly 1 million patients. It has shown a significant link between loss of a partner and development of atrial fibrillation.

We found the risk of developing an irregular heartbeat for the first time was 41 percent higher among those grieving a partner's loss compared to those who hadn't experienced such loss.

We also found the condition could persist for up to a year after the tragic event.

This is concerning as atrial fibrillation is associated with increased risk of death, stroke, and heart failure. An irregular heartbeat has also been linked to lower quality of life. A person's estimated lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation is between 22 percent and 26 percent and the condition is one of the few heart diseases with increasing incidence.

A closer look at our study

In our population-based case-control study, we took information about 88,612 patients in Denmark who were newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation between 1995 and 2014 and compared it with 886,120 healthy people.

Both groups were matched on age and sex. Among those with atrial fibrillation, 17,478 had lost a partner. In the control group, this number was 168,940.

We looked at several factors that might influence the risk of atrial fibrillation, including age, sex, patients' underlying health conditions, and the health of their partner a month before the death.

We found the risk of developing atrial fibrillation was highest eight to 14 days after a partner's loss and remained elevated for a year. The risk was higher in those under 60 years old and the effect was most dramatic in those who had unexpectedly lost a healthy partner.

The heightened risk was apparent irrespective of gender and other underlying health conditions.

Those with partners who were relatively healthy in the month before death were 57 percent more likely to develop an irregular heartbeat, but no increased risk was seen among those whose partners were ill and expected to die soon.

The link between body and mind

Our study is the first to show that severe stress could play a significant role in the development of atrial fibrillation.

The exact mechanisms linking the mind and heart, however, aren't certain.

Studies have suggested acute stress may directly disrupt normal heart rhythms and prompt the production of chemicals involved in inflammation, which is a physical response to injury or infection.

Bereavement, such as after the loss of a partner, often brings about symptoms of mental illness such as depression, anxiety, guilt, anger, and hopelessness. Losing a partner to death ranks highly on a psychological scale of severely stressful life events.

Such stress could affect basic hormonal processes. The release of adrenalin, for instance, is useful in acute danger – as it increases your heart rate and diverts blood to your muscles so you can run or fight – but it can disrupt heart rhythm if the release is excessive and prolonged.

Acute mental stress may also create imbalance in the central nervous system – the autonomic nervous system – that controls many basic functions. It also modulates our heart frequency and the electrical nerve pathways that run through the heart to the muscle, facilitating a synchronised contraction of the heart chambers.

Those grieving need special attention

Our study indicates that people experiencing severe mental stress from bereavement are a vulnerable group that might need more medical attention.

With a biologically plausible association, early identification of this group is currently a major challenge in the health-care system.

The study's findings don't just have significant clinical relevance though. We are currently experiencing substantial levels of stress in modern society. And while stress is a potentially modifiable risk factor, many people develop stress-related illnesses that are a key driver to growing health-care costs.

Simon Graff, Research assistant, Institute for Public Health, Aarhus University.

This article was originally published by The Conversation. Read the original article.