It's long been thought that the first people to populate America thousands of years ago migrated southwards through a frosty corridor in what is now called Canada.

But a new study suggests that this chilly passage – measuring some 1,500 kilometres long – could not have sustained travellers at the time the migration took place, meaning the first Americans must have entered North America via a different route.

"What nobody has looked at is when the corridor became biologically viable," said evolutionary geneticist Eske Willerslev from the University of Cambridge in the UK.

"When could they actually have survived the long and difficult journey through it?"

An international team of researchers led by Willerslev extracted ancient plant and animal DNA from lake sediment cores in a portion of the land where the corridor once stood.

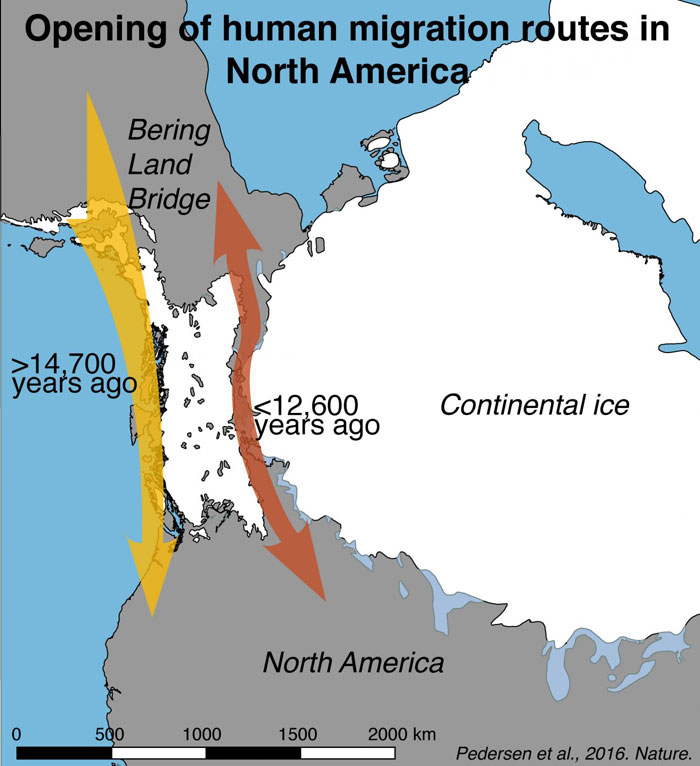

The passage originally formed once two massive ice sheets – called the Cordilleran and the Laurentide – began to recede about 13,000 years ago.

The ecosystem that emerged from the corridor's fossils suggests there simply wouldn't have been enough food to feed any would-be Americans making the trek back when the migration is supposed to have happened.

"The ice-free corridor was long considered the principal entry route for the first Americans," said one of the team, Mikkel Winther Pedersen from the University of Copenhagen in Denmark. "Our results reveal that it simply opened up too late for that to have been possible."

According to the researchers, the ice-free corridor would only have become passable for human travellers about 12,600 years ago, at which point there would have been enough plants and animals to keep migrating humans alive on the road.

But since evidence of the earliest known Americans, the Clovis, pre-dates this point in time – it means they must have travelled south another way.

The Clovis culture – named after ancient stone tools found in Clovis, New Mexico – is thought to date back to between 13,200 to 12,900 years ago.

"The bottom line is that even though the physical corridor was open by 13,000 years ago, it was several hundred years before it was possible to use it," said Willerslev.

"That means that the first people entering what is now the US, Central and South America must have taken a different route. Whether you believe these people were Clovis, or someone else, they simply could not have come through the corridor, as long claimed."

Mikkel Winther Pedersen/University of Copenhagen

Mikkel Winther Pedersen/University of Copenhagen

So which way did the first Americans come to America? Well, nobody knows for sure, but the researchers think the early travellers most likely took the scenic route, migrating southwards along the Pacific coast (you can see the two routes charted on the graph above).

That's only a hypothesis for now, but it could help explain how early people like the Clovis first made their home in America – and possibly even cultures we don't know about that came before them.

"There is compelling evidence that Clovis was preceded by an earlier and possibly separate population," said one of the researchers, archaeologist David Meltzer from Southern Methodist University, "but either way, the first people to reach the Americas in Ice Age times would have found the corridor itself impassable."

In addition to helping us better understand the movement of these ancient peoples, the research also demonstrates new ways in which scientists can use fossil DNA to recreate entire genetic landscapes that existed millennia ago.

"Instead of looking for specific pieces of DNA from individual species, we basically sequenced everything in there, from bacteria to animals," said Willerslev.

"It's amazing what you can get out of this. We found evidence of fish, eagles, mammals, and plants. It shows how effective this approach can be to reconstruct past environments."

The findings are reported in Nature.