The gene pool of modern West Africans contains the 'ghost' of a mysterious hominin, unlike any we've detected so far. Similar to how humans and Neanderthals once mated, new research suggests this ancient long-lost species may have once mingled with our ancestors on the African continent.

Using whole-genome data from present-day West Africans, scientists have found a small portion of genetic material that appears to come from this mysterious lineage, which is thought to have split off from the human family tree even before Neanderthals.

Today, it's thought (although still being debated) that anatomically modern humans originated in Africa, and that once these populations migrated to Europe and Asia, they interbred with closely-related species like Neanderthals and Denosovans.

As such, modern West Africans, like populations in Yoruba and Mende, do not possess genes from either of these ancient species, but that doesn't mean there was no intermixing. In fact, recent evidence suggests the genetic past of West Africans may contain a similarly juicy narrative.

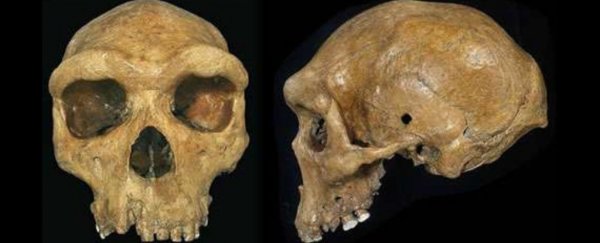

The idea is hard to confirm, because ancient human remains and DNA are scarce on the African continent and even harder to find in West Africa.

Fortunately there is one way to get an idea of how ancient humans mixed that doesn't involve studying remains: modern genomics. Researchers decided to compare 405 modern genomes from the Yoruba and Mende populations with genomes from Neanderthals and Denisovans.

To their surprise, they also found traces of another as-yet-unknown ancient hominin species in their genomes.

Similar to how modern humans outside of Africa still hold traces of Neanderthal genes, the authors found populations in West Africa derived between 2 and 19 percent of their genetic ancestry from this as-yet-undiscovered ancient hominin.

Interestingly, this isn't the first time 'ghost' species of unknown extinct ancestors have been found in modern DNA. Researchers looking at Eurasian DNA have previously found traces of at least three as-yet-undiscovered ancient hominins in modern human genomes. But this is a first for modern West African DNA.

The findings are supported by several other studies that suggest there have been multiple interbreeding events between archaic and modern human populations in Africa.

This is known as genetic introgression, but while it's become a popular theory, exactly where, when and to what extent this mixing occurred is unknown.

In the fossil record, modern humans show up around 200,000 years ago, but in parts of sub-Saharan Africa, a few fossils have been found with a mix of archaic and modern features that are only 35,000 years old.

"One interpretation of the recent time of introgression that we document is that archaic forms persisted in Africa until fairly recently," the authors of the new study suggest.

"Alternatively, the archaic population could have introgressed earlier."

In the end, neither is mutually exclusive, but the authors say we will need more analysis of African genomes across the continent before we can understand the true makeup of our ancestors.

The study was published in Science Advances.