Last week, NASA administrator Bill Nelson told us we'd see the "deepest image of our Universe that has ever been taken" on July 12, thanks to the newly operational James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). And we know many of you excitedly marked the date in your calendar.

But over the weekend the space agency announced that they'd actually be releasing one the very first image a day ahead of schedule – at 5.30pm EDT (2130 UTC and 7.30am AEST on Tuesday 12 July).

The first image will be released by US President Joe Biden in a special live stream that you can view in real time below. We'll be watching live and sharing the first image with all of you as soon as it's available. Suffice to say, we can't freaking wait!

What can we expect to see?

JWST can peer back in time to just a hundred million years after the Big Bang – virtually the toddler years for our 13.8 billion year old Universe. This is all thanks to its huge primary mirror and ability to see the ancient, stretched-out infrared light of distant space.

Because the Universe is expanding, light from those very first stars shifts from the ultraviolet and visible wavelengths into the longer infrared wavelengths – which JWST can detect in never-before-seen detail.

"If you think about that, this is farther than humanity has ever looked before," Nelson said during a press briefing last week at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore.

JWST was launched in December last year and is now orbiting the Sun a million miles (1.5 million kilometers) away from Earth.

"It's going to explore objects in the solar system and atmospheres of exoplanets orbiting other stars, giving us clues as to whether potentially their atmospheres are similar to our own," said Nelson in the press briefing.

"It may answer some questions that we have: Where do we come from? What more is out there? Who are we? And of course, it's going to answer some questions that we don't even know what the questions are."

What are Webb's first targets?

NASA has conveniently let us know a list of JWST's first targets.

The Carina Nebula

The Carina Nebula. (NASA, ESA, Mario Livio (STScI), Hubble 20th Anniversary Team (STScI))

The Carina Nebula. (NASA, ESA, Mario Livio (STScI), Hubble 20th Anniversary Team (STScI))

Located around 7,600 light-years away in the southern constellation of Carina, the Carina Nebula is one of the biggest and brightest nebulae in our skies.

Hubble imaged the Carina Nebula several times, including in infrared; Webb's images are expected to blow Hubble's infrared ones away. After all, Hubble is primarily an optical and ultraviolet instrument.

WASP-96b

One of the objectives Webb has been tasked with is peering into the atmospheres of planets outside the Solar System, or exoplanets. WASP-96b is one of these, and an absolutely fascinating subject for what ought to be the first of many such surveys.

Southern Ring Nebula

The Southern Ring Nebula. (The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA/NASA))

The Southern Ring Nebula. (The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA/NASA))

The Southern Ring Nebula, AKA NGC 3132, around 2,000 light-years away, is a gorgeous, glowing blob in the southern constellation of Vela. Although it shares classification with Carina Nebula, they're more like astronomical opposites: it's the breathtaking, beautiful remains of a binary star that is in the process of dying.

Stephan's Quintet

Stephan's Quintet. (NASA, ESA, and the Hubble SM4 ERO Team)

Stephan's Quintet. (NASA, ESA, and the Hubble SM4 ERO Team)

Webb has also been peering much farther from home. Stephan's Quintet is a group of galaxies located 290 million light-years away, in a formation so tight that it doesn't look real. In actuality, only four of the five galaxies are interacting; the fifth is much closer to us, only about 40 million light-years away.

SMACS 0723

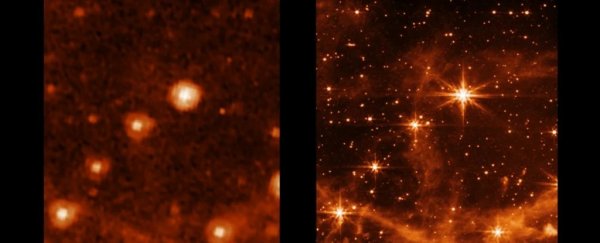

For its first deep field, Webb has peered into a patch of sky called SMACS 0723, in the southern constellation of Volans.

SMACS 0723 is a particularly good target for this sort of observation, because there are massive clusters of galaxies in the foreground. These act like a giant cosmic magnifying glass. Because of the immense mass, their gravity causes pronounced curvature of the space-time around them, with the effect of magnifying light from more distant objects.

We're not sure which of these targets will be the subject of the first image to be released on Monday, but we can't wait to find out. Watch this space!