Methane leaks from the environment and human activity are a serious greenhouse gas problem. Methane is many times more effective than carbon dioxide at trapping heat, and scientists now say the Moon plays a key role in how much of the gas gets released.

It's all down to the tides and the tugging effect that the Moon's gravitational pull has on them – a phenomenon we can quantify. By placing a piezometer instrument in the Arctic Ocean for four days and nights, researchers were able to measure temperature and pressure changes over time.

What they found was that the presence of methane gas close to the seafloor rises and falls with the tides, which is an important contributing factor when it comes to methane release, and one that impacts the climate change we're witnessing now and into the future.

The piezometer being retrieved. (P. Domel)

The piezometer being retrieved. (P. Domel)

"We noticed that gas accumulations, which are in the sediments within a metre from the seafloor, are vulnerable to even slight pressure changes in the water column," says marine geophysicist Andreia Plaza-Faverola from the University of Tromsø – The Arctic University of Norway.

"Low tide means less of such hydrostatic pressure and higher intensity of methane release. High tide equals high pressure and lower intensity of the release."

These methane leaks in the Arctic Ocean have occurred for thousands of years, caused by factors such as seismic and volcanic activity, but there's plenty more to learn about the mechanisms that cause this leakage and affect its rate.

That's where the Moon and the tides come in. The researchers say tides could be used as a way of predicting the amount of gas released from the Arctic Ocean from day to day, even with variations in tidal height of less than 1 metre (3.3 feet).

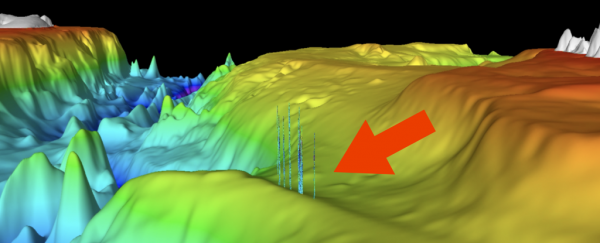

One of the takeaways is that gas release from the seafloor is more widespread than the data from conventional sonar surveys show, and we may have underestimated just how much gas the Arctic is leaking at the moment, even if it's not all released at once.

"Earth systems are interconnected in ways that we are still deciphering, and our study reveals one of such interconnections in the Arctic," says Plaza-Faverola.

"The Moon causes tidal forces, the tides generate pressure changes, and bottom currents that in turn shape the seafloor and impact submarine methane emissions."

The study also raises the possibility that rises in sea levels might counteract the release of methane from the oceans, as the greater water pressure keeps the gas trapped for longer. It's just one of a multitude of factors that scientists have to weigh up.

Next, the researchers want to capture more data across a longer period of time to see how changes in tides are affecting the release of methane in the region as a whole: from deep-water sites like this one, to shallow-water areas where the effect of tidal variations on gas release is likely to be even greater.

While tidal changes have been linked to methane emissions in the past, the geographical site of this study and the fluctuations observed by even minor differences in pressure make it a crucial new information point for future climate change modelling.

"It is the first time that this observation has been made in the Arctic Ocean," says marine geologist Jochen Knies.

"It means that slight pressure changes can release significant amounts of methane. This is a game-changer and the highest impact of the study."

The research has been published in Nature Communications.