A 2003 marine heat wave in the waters around Greenland continues to impact North Atlantic ocean ecosystems decades on, with a sudden and strong increase in marine heat wave frequency persisting ever since.

Marine biologists from Germany and Norway reviewed more than 100 scientific studies and found that marine heat waves (MHWs) in and after 2003 led to "widespread and abrupt ecological changes" across all levels of the ocean's ecosystems – from tiny, single-celled protists to commercially important fish species and whales.

"The events of 2003, which followed a preceding warm year 2002, signaled the beginning of a prolonged heating phase across numerous North Atlantic locations unlike any observed before," writes marine ecologist Karl Michael Werner of the Thünen Institute of Sea Fisheries in Germany and his colleagues.

"Although the year 2003 stands out as [the] maximum, where most MHWs were counted, several years in the following period showed similarly high numbers."

Related: Study Confirms 'Abrupt Changes' in Antarctica – And The World Will Feel Them

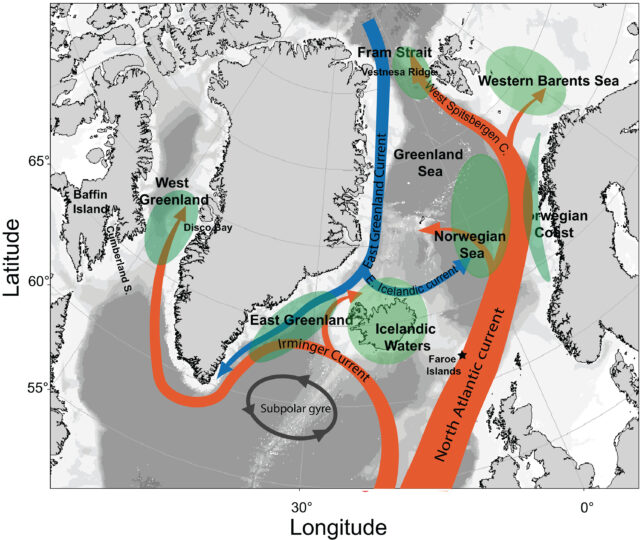

The 2003 marine heat wave gripped the North Atlantic when a weak subpolar gyre allowed vast quantities of warm, subtropical water to gush into the Norwegian Sea via the Atlantic Inflow. At the same time, Arctic waters that usually flow into and cool the Norwegian Sea were unusually weak.

All this led to a stark decrease in sea ice and substantial sea surface temperature increases in the region. In the Norwegian Sea, rising temperatures penetrated to depths of 700 meters (2,300 feet).

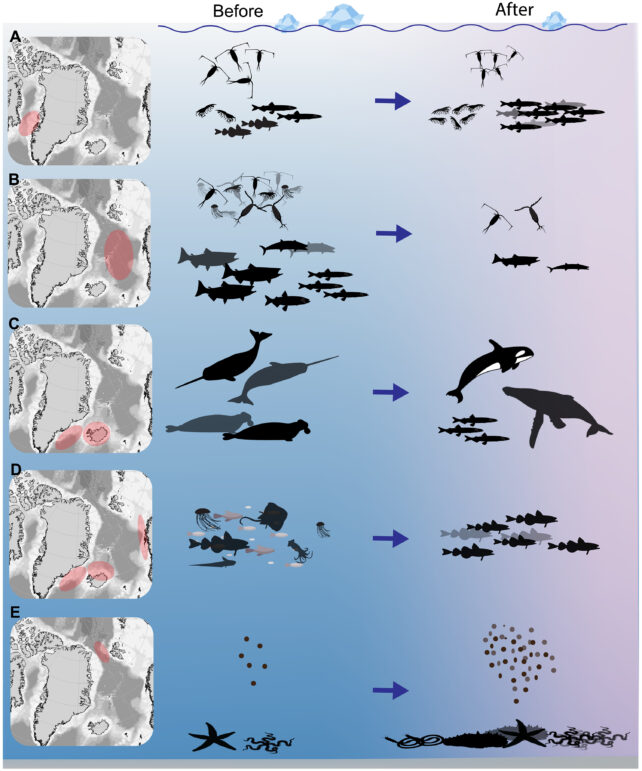

As is typical in warming waters, cold-water creatures tended to lose out, with those that thrive in warmer conditions spreading out into their newfound ecological niche.

"Every examined region showed a reorganization from species adapted to colder, ice-prone environments to those favoring warmer waters and the event's impacts altered socioecological dynamics," the authors explain.

A sudden reduction in sea ice opened the waters to baleen whale species in 2015. Orcas – mostly absent from these parts for more than 50 years – have also been sighted more frequently since 2003.

"Conversely, catches of ice-dependent, cold water–adapted narwhals (Monodon monoceros) and hooded seals (Cystophora cristata) southeast of Greenland either significantly declined after 2004 or experienced a considerable decrease in the mid-2000s," the authors report.

Bottom-feeders such as brittle stars and polychaete worms chowed down on the massive phytoplankton blooms that eventually fall to the seabed in the wake of heatwaves. Atlantic cod, an opportunistic predator, is another species that seemingly took advantage of newly available food.

The 2003 heat wave coincided with the sudden disappearance of sandeel (Ammodytes), an important prey for larger fish such as haddock, and subsequent ecological shifts have paralleled dwindling capelin populations.

Capelin are a vital food source for Atlantic cod and whales in the North Atlantic, but these fish have shifted north to seek colder feeding and spawning grounds. If things continue to heat up, there's not much further north they can go.

Such massive changes can throw the system out of balance in a way that may be detrimental to even the most hardy of sea creatures in the long-run.

"The resulting ecological reorganization across these regions underscores the profound impact of extreme events on marine ecosystems," Werner and colleagues write.

"One can predict how rising temperatures affect organisms' metabolisms. But a species won't benefit from such changes if it is eaten by predators after moving northwards or does not find suitable spawning grounds in the new environment," Werner adds.

Marine heat waves like this aren't just random occurrences: There's good evidence that their intensity, frequency, and scale are linked to humans burning fossil fuels, which releases greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Most of the excess heat these greenhouse gases trap gets absorbed by the ocean.

While the effects of human-induced climate change vary regionally, we know marine heat waves are one of its many symptoms.

Related: Gigantic Wave in The Pacific Was The Most Extreme 'Rogue Wave' on Record

In the Arctic, marine heat waves can contribute to further warming, as melting sea ice exposes darker oceans that reflect less light and absorb yet more heat.

It's a worrying feedback loop, and while the consequences are fast becoming apparent, the mechanisms driving marine heat waves are not fully understood.

"The repeated heat waves following 2003 may have produced additional yet undetected ecological implications potentially interacting with other stressors," Werner and team conclude.

"Understanding the importance of the subpolar gyre and air-sea heat exchange will be crucial for forecasting MHWs and their cascading effects."

The research was published in Science Advances.