Antarctica is a notoriously icy place, and yet its clouds, new research reveals, are surprisingly lacking in the stuff.

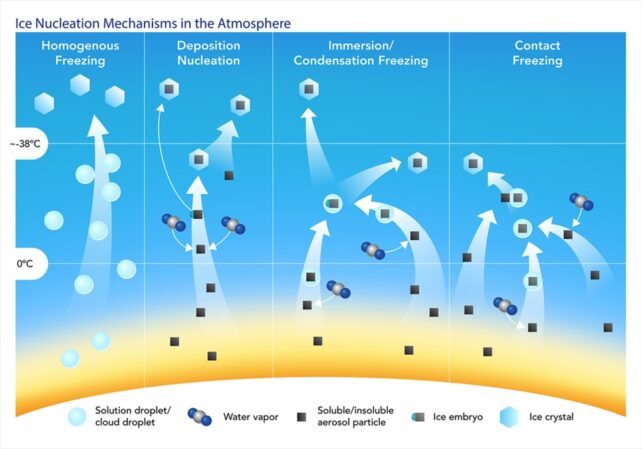

Tiny particles in the atmosphere are required for ice crystals to form inside clouds. These so-called ice-nucleating particles, or INPs, can include mineral dust, wind-blown soil, ash, sea spray particles or proteins shed from living creatures.

Ice forms in clouds that are otherwise not cold enough by crystallizing on these airborne particles.

Related: There's Something Different About Clouds in Antarctica, And It Could Be Important

But over the Southern Ocean around Antarctica – the world's largest ice desert – these particles are surprisingly scarce, scientists have revealed by analyzing samples of air collected from several Antarctic outposts.

"To our knowledge, there has never been such a long time series of filters from which INPs have been determined on the Antarctic mainland," says tropospheric scientist Heike Wex from the Leibniz Institute in Germany.

"We suggest that their low abundance may be due to an absence of efficient biological sources, present in other regions of the globe, including the summertime Arctic," Wex and team report in their published paper.

The researchers only sampled the air near three Antarctic stations, but they think the low concentrations of ice nuclei they observed at the two southernmost stations may extend to other parts of the icy continent. More samples would help fill in the gaps.

As it is, the study adds to our understanding of how Antarctica's anomalous clouds may be shielding the Southern Hemisphere from some of the heat of climate change.

That's because with fewer ice nuclei in the air, more of the water in clouds remains liquid, albeit supercooled. And these water-laden clouds reflect more sunlight back into space than icy clouds do.

However, the protection these clouds offer the Southern Hemisphere may be under threat, according to tropospheric scientist Silvia Henning, also of the Leibniz Institute.

"The concentration of ice nuclei in Antarctica could increase due to global warming, as retreating glaciers expose more land to vegetation and the biosphere could become more active," Henning explains.

If more ice nuclei are thrust into the atmosphere, it could reduce the reflective power of otherwise sodden clouds. That could, in turn, impact the climate of the region by adding to a feedback loop of warming.

"Therefore," Henning says, "determining the current state [of Antarctica's INPs] can be helpful in assessing the potential impacts of future changes."

The research is published in Geophysical Research Letters.