A dolphin that swam the waters of the Amazon basin 16 million years ago is a contender for the largest freshwater toothed whale the world has ever seen.

The ancient beastie measured up to 3.5 meters (11.5 feet) in length, a good deal larger than the 2.7-meter (9-foot) pink Amazon river dolphins that feast on piranhas in the habitat today.

Though a great deal shorter than the largest dolphin in today's oceans – the orca – the newly discovered species does highlight the ancient biodiversity found in the waterway's history.

Interestingly, the newly discovered Pebanista yacuruna is not most closely related to the current Amazon dolphins, but dolphins found half-a-world away in the Ganges and Indus rivers of India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Bangladesh.

"We discovered that its size is not the only remarkable aspect," says paleontologist Aldo Benites-Palomino of the University of Zurich in Switzerland.

"With this fossil record unearthed in the Amazon, we expected to find close relatives of the living Amazon River dolphin – but instead the closest cousins of Pebanista are the South Asian river dolphins (genus Platanista)."

Freshwater river dolphins look a lot like marine dolphins that haven't finished baking. They tend to be pinker, with longer beaks, but they do look fairly similar. However, both dolphin groups – freshwater and marine – are descendants of distinct cetacean lineages.

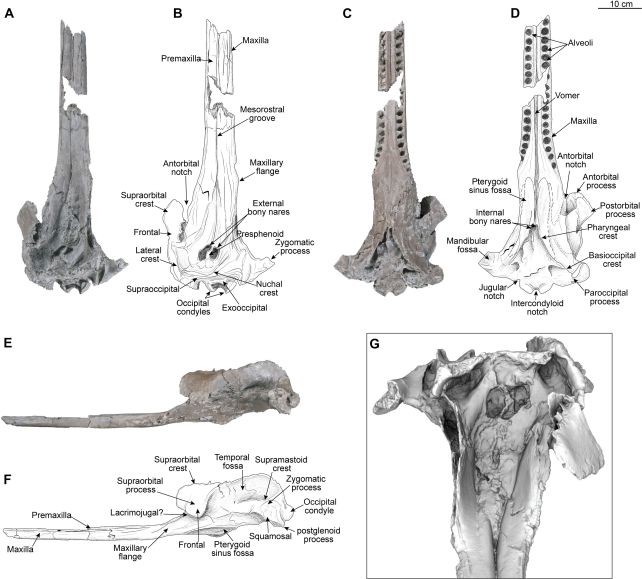

Pebanista was discovered from a single skull found buried in the Pebas Formation, Miocene fossil beds that preserve the remains of many ancient animals that once roamed the Amazon basin. But that skull is sufficient to infer a lot about what the animal was like while it lived.

Although it's incomplete, enough remains of the features of the skull that Benites-Palomino and his colleagues were able to draw comparisons with other extinct and living animals. Like the species of the Platanistid genus, it had large crests in its forehead, structures associated with the ability to echolocate.

"For river dolphins, echolocation, or biosonar, is even more critical as the waters they inhabit are extremely muddy, which impedes their vision," says paleontologist Gabriel Aguirre-Fernández of the University of Zurich.

And, like other river dolphins, Pebanista has a very long snout, or rostrum. This snout helps living river dolphins hunt and snare the fish on which they predominantly feed, suggesting that Pebanista had a similar diet.

As for where it came from, the researchers think that Pebanista started as marine cetaceans that entered the Amazon basin, then filled with a system of rivers and lakes we now call Pebas. Finding it lush and full of things to eat, the new arrivals moved in for good, adapting and making themselves right at home. For a few million years, all was pretty good in dolphin land.

But landscapes change, and that's what happened to Pebanista. When the Pebas system started to change, evolving into the Amazon basin we know today, old habitats disappeared to give way to new ones. The animals on which the dolphin fed disappeared, and so, eventually, did Pebanista.

This left empty an ecological niche that was eventually inhabited and exploited by the river dolphins we find there today. That's a pretty sad ending for Pebanista, but the discovery is an exciting one for us, giving us new information about the adaptability and vulnerability of species in a changing prehistoric world, as well as insight into changing ecosystems.

Pebas may have changed; but the current structure of the Amazonian food web may be more similar to the Miocene than we thought.

"This finding confirms not only an independent marine-freshwater transition of cetaceans in South America," the researchers write, "but also that this diversity in the vast Pebas mega-wetland system might have greatly benefited from the warmer Middle Miocene climatic conditions in the area."

The research has been published in Science Advances.