Secretly held documents from the two most prominent manufacturers of 'forever chemicals' show that industry leaders knew of the harmful health effects of some per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) long before they told the public.

For at least 21 years, company leaders at DuPont – the maker of Teflon – and 3M – the maker of Scotchgard – sat on some seriously concerning results.

In internal research, two of their most popular chemicals, called PFOS and PFOA, were proven to have all sorts of adverse health effects that government officials weren't made aware of.

Only in 1998, when DuPont was sued for dumping more than 7,000 tons of PFAS-laced sludge into the Ohio River, did the company's secrets first come to light.

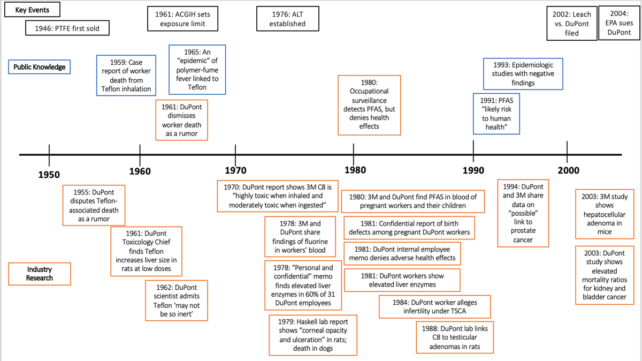

Now, a small sampling of company documents from DuPont and 3M, spanning 1961 to 2006, has allowed researchers to assemble a timeline of the deception.

These documents were initially obtained by the attorney Robert Bilott, who successfully sued DuPont for PFAS contamination in the early 2000s.

More recently, they were donated to researchers at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), by the producers of a 2018 investigative documentary on DuPont called The Devil We Know.

"Having access to these documents allows us to see what the manufacturers knew and when, but also how polluting industries keep critical public health information private," says Nadia Gaber, a public health researcher at UCSF at the time, who led the research.

"This research is important to inform policy and move us towards a precautionary rather than reactionary principle of chemical regulation."

Today, chemical regulations in the US are usually made in hindsight, putting public health at risk. All too often, novel materials are manufactured first and tested for toxicity only after they appear on the market.

The harms of this approach are more than evident when looking at the history of 'forever chemicals'.

PFAS are nicknamed 'forever chemicals' because they take ages to break down in the environment. Since the 1940s, this class of chemicals has been used in non-stick cookware, fabric treatment, cosmetics, and food packaging.

Of the more than 12,000 known PFAS variants available today, two clearly show adverse health outcomes, including increased risks of cancer and birth defects.

In the early 2000s, PFOA and PFOS were finally phased out of production in the US, but by then, they had already spread far and wide.

At first, both DuPont and 3M claimed these chemicals were biologically inert. But investigative reporting and legal disclosures show that industry leaders knew this wasn't true for many years.

In the 1970s, internal documents reveal that DuPont knew PFOA was "highly toxic" when inhaled and "moderately toxic" when ingested.

As far back as 1961, documents show that Teflon's Chief of Toxicology knew PFOA had "the ability to increase the size of the liver of rats at low doses" and should "be handled 'with extreme care' and that 'contact with the skin should be strictly avoided.'"

Later on, in the early 1980s, DuPont and 3M learned of pregnant workers who were exposed to PFAS suffering miscarriages or having children with birth defects.

In 1991, Dupont denied any adverse health effects.

It took 30 years after industry knowledge for the first peer-reviewed papers to connect birth defects to PFAS in the scientific literature.

To this day, over 90 percent of pregnant people in the US continue to be exposed to these potentially harmful chemicals.

Even at minor traces, there's a chance that they cause adverse health effects.

The US Environmental Protection Agency recently dropped the safety guidelines for PFOA and PFOS in drinking water from 70 parts per trillion to below 0.02 parts per trillion – an adjustment that could mean more than half the US is exposed to harmful chemicals when they drink from the tap.

To this day, researchers at UCSF point out that "no federal enforceable limits on any PFAS chemicals have been established in the US."

While not all PFAS chemicals are bound to be as dangerous as PFOA or PFOS, it's fair that the public is concerned about the potential health effects.

The strategies DuPont and 3M used to suppress research and influence government regulations are reminiscent of those employed by tobacco companies, researchers say.

History could easily keep repeating itself if something doesn't change.

The report was published in the Annals of Global Health.