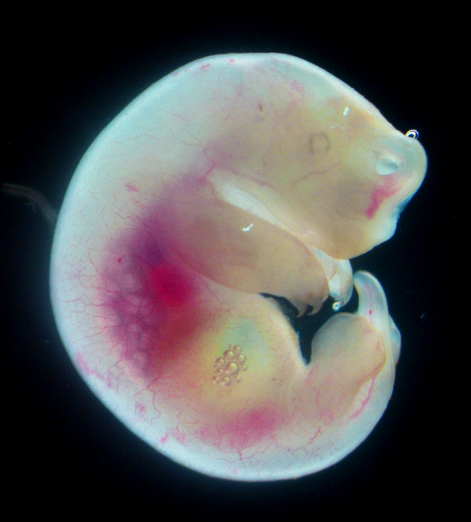

A mere 13 days after conception, a rice-grain-sized pink blob, striving to become a dunnart joey, heaves itself out of its mother's birth canal, drags its gelatinous body through a forest of fur using its stubby translucent forelimbs to reach its mother's pouch and latch onto her sustenance-providing teat.

These undercooked (by most mammal standards) marsupial babies somehow manage to achieve this epic feat without a single solid bone in their bodies. University of Melbourne researchers just discovered newborn dunnarts crawl before they even grow a skeleton.

Fat-tailed dunnarts (Sminthopsis crassicaudata) are mouse-sized, nocturnal carnivores, related to quolls, Tasmanian devils, and the extinct Tasmanian tiger (the Dasyuridae family). Their 'fat tails', up to 7 centimeters (2.8 inches) long, store energy from the insects, spiders, small frogs, and lizards they eat to help them withstand the extremes of their semi-arid habitat.

Like all marsupials, dunnarts give birth to young at a super early stage of development. They have around seven joeys per litter on average and breed twice a year.

"Almost all of their development happens after birth in the pouch, meaning we can directly observe the joeys as they develop," explained developmental biologist Laura Cook.

Using 3D scans from micro-computed tomography (microCT), Cook and colleagues did just that and discovered the newborns' astonishing lack of mineralized bones.

"This was somewhat of a surprise as we know that other marsupial species like kangaroos and tammar wallabies have accelerated development of the forelimb and oral bones with these bones present before or at birth," Cook and fellow developmental biologist Andrew Pask wrote.

These are the body parts newborn marsupials use the most in their first epic journeys from the birth canal to pouch, but tammar wallabies have a gestation period of at least 25 days and kangaroos over 30.

Dunnarts are born after only 13 days in their mother's womb, yet they're still further developed in those important body areas compared to their other parts, such as hindlimbs.

A newborn dunnart, with its tiny grabby arms. (@Laura_Cook/Twitter)

A newborn dunnart, with its tiny grabby arms. (@Laura_Cook/Twitter)

These fierce little marsupials are born with heads almost 50 percent of their total body length. But instead of a spine to support them, the heads are propped up just with swelling of the area that will become the neck part of their spine – something also seen in Tasmanian devils.

As for how newborn dunnarts move their tiny developing muscles without bony anchors to journey to their mother's pouch:

"Forelimb movement is mostly controlled by the muscles of the back and shoulders," Cook told ScienceAlert.

"When they're born, dasyurids have these same large muscles, but instead of attaching to bone, they attach to a transient structure made of cartilage known as the shoulder arch. The shoulder arch provides structural support and anchors the muscles used to make the journey to the pouch."

The dunnart's lack of bones, however, did not last long.

"Approximately 24 hours after birth, the first bones were visible in the forelimbs and jaw of the dunnart joeys," Cook and Pask wrote.

Insights into dunnart development can help us understand our own evolutions as they provide an early mammalian comparison point, Cook explained. Marsupials separated from our line of placental mammals at least 160 million years ago.

These findings could also help biologists explore the molecular processes behind skeletal development, something that is much trickier to observe in animals that undergo this development within a womb.

"I've been using the information from this developmental study to look at the regions in the dunnart genome that are driving developmental differences in early craniofacial structures between marsupials and placental mammals," said Cook.

"This analysis gives us a deeper understanding of marsupial development and makes the dunnart a much more powerful laboratory model. We can now start to use this tractable model as we develop novel conservation tools for closely related vulnerable marsupials, such as the Tasmanian devil and the Northern quoll."

There are 19 species of dunnart in Australia, some are threatened, and many are facing population declines due to increasing fires, agricultural clearing, pesticides impacting their food sources, predation by feral predators like cats, and destruction of their habitat by feral herbivores like cattle and camels.

Like a lot of Australia's strange and unique animals, dunnarts are found nowhere else in the world.

"Sadly, a third of Australia's marsupials are currently facing extinction," said Cook. "We still have so much to learn about marsupial biology, and understanding their life history is an important step in enhancing conservation strategies."

This research was published in Communications Biology.