The willow warbler is not one to stop and smell the flowers. Weighing in at a mere 10 grams (0.35 ounces), this restless little songbird regularly traverses multiple continents, flying thousands of kilometres and taking remarkably few breaks.

In fact, researchers in Sweden have now determined this epic trek by the Siberian willow warbler (Phylloscopus trochilus yakutensis) constitutes the longest bird migration in the warbler's weight category.

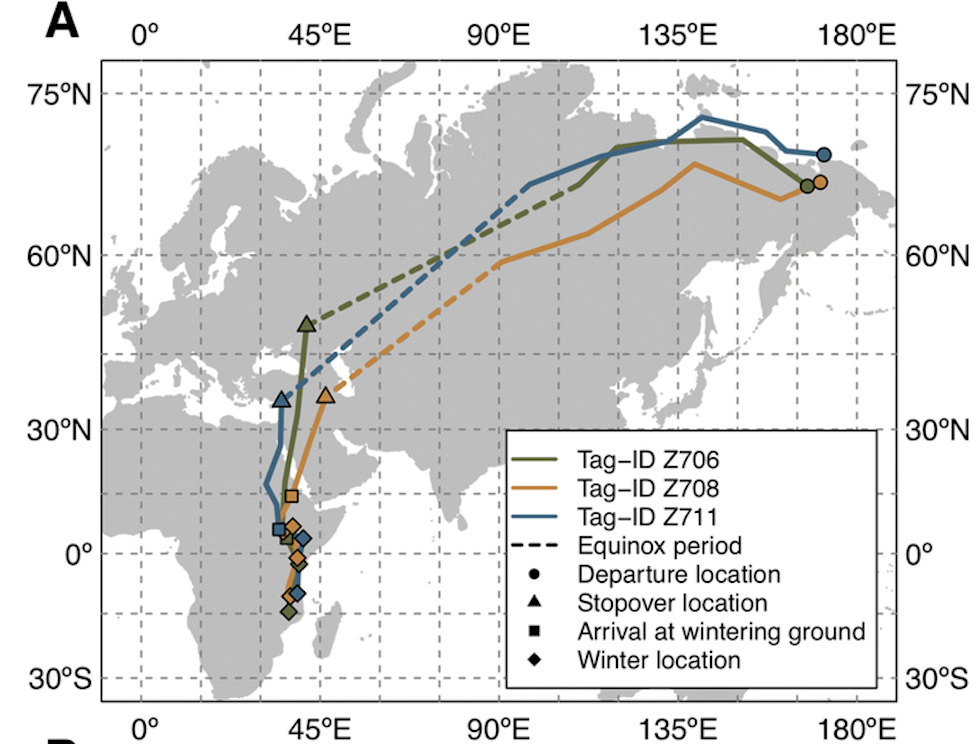

The achievement was calculated during a recent tracking study. Following three male warblers from their nesting site in north-east Russia, the team was able to map their autumn migration, a length no less than 13,000 kilometres (8,000 miles).

And the long-haul might even be longer than that. The study had to be cut short after the batteries in the tracking devices ran out near the end of the trip.

"My guess is that they fly at least another 1,000 kilometres to south-east Africa," predicts co-author Susanne Åkesson, who studies songbird orientation at Lund University.

The willow warbler is a rather small and plain species, measuring only 11 to 12.5 centimetres (4.3 to 4.7 inches) long. They would be easy to overlook, but these remarkable creatures should not be judged by appearance alone.

Each autumn, a subspecies of willow warbler leaves its nest in eastern Siberia and flies to either south-west Asia or the eastern Mediterranean. The subspecies, called Siberian willow warblers, spend about a quarter of their day flying at about nine metres per second.

And while these brave migrants make frequent stops along the way to rest and refuel, they only take their first prolonged stop in Asia, after five weeks of travel.

A little over two weeks later and they will be off once again, this time to Kenya and Tanzania, where the warblers settle down for winter. Some even keep going on further to southern sub-Saharan Africa.

The new study found that the whole trip takes over four months to complete, or 93 to 118 days in total. And remember, that's just one way. For the warblers, this is a bi-annual event.

(Sokolovskis et al/Lund University)

(Sokolovskis et al/Lund University)

Sure, there are other birds that can migrate much further. The arctic tern, for instance, completes the world's longest migration, flying around 70,000 kilometres each year (40,000 miles). But the arctic tern is also ten times larger in weight than the willow warbler.

"I think it's fascinating — they are so small and migrate at least 13,000 kilometres one way. There are no other studies that show that birds of that size can migrate that far," says Åkesson.

"Even more impressive perhaps is that they make the journey alone in their first year of life."

From the very start, the willow warbler's sense of direction is impeccable. In fact, this jet-setting bird comes with a whole set of biological compasses that allow it to navigate the globe.

By comparing the actual route that these birds took with other possible routes, the researchers identified two forms of inherent navigation they think the birds might be using.

The findings suggest the warblers are drawing on information from the Sun and Earth's magnetic field to point themselves in the right direction.

The bird's internal solar compass, for instance, works by compensating for time changes during the migration, syncing the internal body clock to local time only after a few days of rest.

The warblers also use a magnetic compass that is crucial for accurate navigation. The researchers think this internal compass allows the bird to measure the inclination angle of the Earth's magnetic field, so they can find their way from point to point.

These two skills are crucial for accurate migration, and migration without accuracy is pretty useless. Travelling huge distances allows the willow warbler to explore distant and precious resources, but timing is everything.

These gifts from nature are only around for a limited time, and getting from location to location on schedule, to be at the right place at the right time, is a question of survival.

The willow warbler comes prepared.

This study has been published in Movement Ecology.