The water scavenger beetle Regimbartia attenuata isn't known for much.

The family of beetles they're part of can be pests in fish hatcheries, and they're well suited to the humid tropics.

But now, R. attenuata is giving this beetle clan a new claim to fame – thanks to the ability to quickly wiggle its way out of a frog butt after being eaten.

"Here, I report active escape of the aquatic beetle R. attenuata from the vents of five frog species via the digestive tract," Kobe University ecologist Shinji Sugiura writes in a new paper.

"Although adult beetles were easily eaten by frogs, 90 percent of swallowed beetles were excreted within six hours after being eaten and, surprisingly, were still alive."

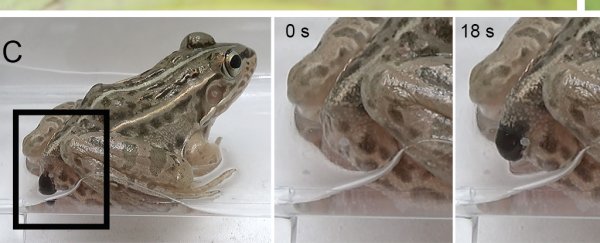

In what has to be one of the weirdest experimental setups we've seen in a while, Sugiura took R. attenuata and black-spotted pond frogs (Pelophylax nigromaculatus), placed them in a lab, let the frogs eat the beetles, and then recorded how long it took the beetles to emerge from… the other end.

And look, they were speedy. When Sugiura put wax on the beetles' legs (therefore stopping them from moving) they took between 38 and 150 hours to be digested and eventually excreted. Those little guys did not survive the ordeal.

But when the beetles were eaten with all their movement faculties intact, the vast majority of them emerged unscathed in just a few hours, and one particularly prompt bug got out of there in just under 7 minutes.

After their ordeal, they lived long, happy lives for weeks afterwards, seemingly unfazed by their trip through the digestive system.

Most of the time, when a creature emerges, still alive, from the back end of a predator like this, it's a passive situation. Usually the creature in question has specific adaptations for these journeys, allowing them to survive extreme pH and no oxygen for quite a while.

But this water beetle doesn't seem to survive if it sits idly and waits to emerge via the frog's digestion mechanisms. Instead, in what's being called the first documented "active prey escape", the little beetle powers through the frogs' oesophagus, stomach, and small and large intestine, until it reaches the cloaca, which the paper calls the "vent".

Once the beetle reaches that impasse, Sugiura thinks that the bug might have another trick up its tiny sleeve.

"R. attenuata cannot exit through the vent without inducing the frog to open it because sphincter muscle pressure keeps the vent closed," Sugiura writes in the paper.

"Individuals were always excreted head first from the frog vent, suggesting that R. attenuata stimulates the hind gut, urging the frog to defecate."

But not all water beetles have the same escape act as R. attenuata. Sugiura also experimented with other beetles and other types of frogs.

The four other frog species were not much of an issue for R. attenuata, with the large majority of beetles exiting unharmed the same way as in the black-spotted pond frog.

But when the pond frog was provided with a different beetle that's part of the same family - Enochrus japonicus, the poor things did not fare as well. All went in one end, and then over 48 hours later, all were excreted, each one very much dead.

By now we're sure you're thinking you have way more information about frog butt escapes then you ever wanted to know, but there are still many unanswered questions.

For example, what exactly is the beetle doing in there inside the frog to make this rear-end exit possible? And are there any other water beetles that can Houdini their way out of a butthole like this?

Only time will tell, but it's important work, and we promise to be on the case.

The research has been published in Current Biology.