We've seen how 3D-printing can revolutionize certain manufacturing processes – whether on Earth or anywhere else – but there's a growing field of research looking at ways this can be applied to producing living, biological structures as well.

In a new study, scientists have outlined a new type of 'living ink' or bioink made from programmed Escherichia coli bacterial cells, which can be 3D-printed to create hydrogels in different kinds of shapes that release different types of drugs or absorb toxins, depending on how they're engineered.

What makes this approach different from previous bioinks is how it uses genetic programming to control the mechanical properties of the ink itself – leading to better end results in the finished material and more practical uses for the ink (some existing bioinks don't operate properly at room temperature, for example).

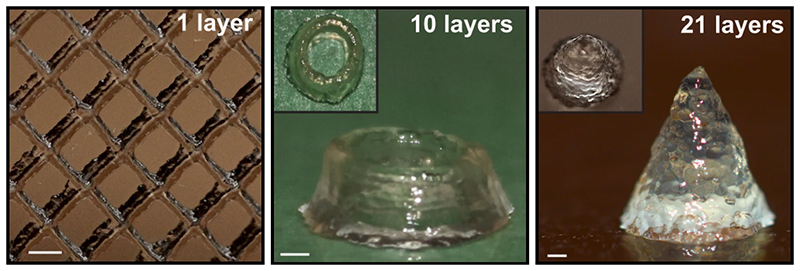

Examples of the printed bioink. (Joshi et al., Nature Communications, 2021)

Examples of the printed bioink. (Joshi et al., Nature Communications, 2021)

"A tree has cells embedded within it and it goes from a seed to a tree by assimilating resources from its surroundings in order to enact these structure-building programs," says chemical biologist Neel Joshi from Northeastern University in Massachusetts.

"What we want to do is a similar thing, but where we provide those programs in the form of DNA that we write, and genetic engineering."

The way it works is by bioengineering the bacterial cells to create living nanofibers. The E. coli cells were combined with other substances to create the fibers, using a chemical process inspired by fibrin – a protein that plays a key part in blood clots in mammals.

These protein-based nanofibers can then be fed into a 3D-printer and manipulated into various shapes. Unlike previous bioinks, this one doesn't use any artificial substances, and is instead entirely biological. It's squeezed out like a toothpaste, but can then keep its form if it is kept from drying out.

So far the technique has been used to make very small objects: a circle, a square, and a cone. But now that the scientists have shown that the microbial ink can be 3D-printed in this way, it opens up more possibilities for the future.

"If you were to take that whole cone and dunk it into some glucose solution, the cells would eat that glucose and they would make more of that fiber and grow the cone into something bigger," says Joshi.

"There is the option to leverage the fact that there are living cells there. But you can also just kill the cells and use it as an inert material."

In experiments, the team was able to combine their bioink with other microbes to perform specific tasks: absorbing toxic chemicals, for example, or delivering an anti- cancer drug. In the future, the ink could also be engineered to self-replicate, the researchers say.

This study builds on previous work by the same team, looking at how E. coli cells could be formed into a hydrogel that self-replicates when it comes into contact with a particular tissue – opening up a new and sustainable method of manufacture that could be used on the Moon and Mars as well as here on Earth.

Although the 3D-printable bioink has only been used on a small scale so far, further down the line it could ultimately be used in everything from building self-healing structures to producing bottle caps that are able to remove dangerous chemicals from water.

"Biology is able to do similar things," says Joshi. "Think about the difference between hair, which is flexible, and horns on a deer or a rhino or something. They're made of similar materials, but they have very different functions. Biology has figured out how to tune those mechanical properties using a limited set of building blocks."

The research has been published in Nature Communications.