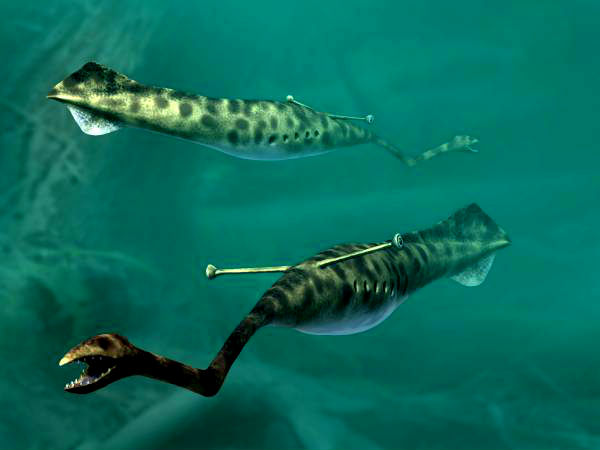

Last year, scientists declared a decades-old mystery solved - that bizarre monstrosity you see in the image above had for years defied classification, but two separate studies said they finally had solid evidence that it was in fact a vertebrate.

But now, more researchers have entered the fray, and say this conclusion is just plain wrong - there's no way this thing can be a fish, which means we still have no idea what it actually is.

Nicknamed the Tully monster, the creature belongs to the ancient genus Tullimonstrum, and is thought to have inhabited the shallow coastal waters of muddy estuaries in the Eastern US around 300 million years ago.

Only a single species, T. gregarium, is known, and fossils of the creature have only ever been found in the Mazon Creek fossil beds of Illinois.

But they were clearly abundant in the region - hundreds of fossils ended up in the Field Museum in Chicago after the species' initial discovery in the 1950s.

As you can see in the reconstruction below, the Tully Monster had fins like a cuttlefish, eyestalks like a crab, and a rather intimidating 'jaw-on-stick':

Nobu Tamura/Wikimedia

Nobu Tamura/Wikimedia

This jumble of body parts has seen it compared to everything from molluscs and arthropods to worms, and more recently, to vertebrates like lampreys.

"This animal doesn't fit easy classification because it's so weird," says Lauren Sallan from the University of Pennsylvania, one of the team behind its most recent analysis.

"It has these eyes that are on stalks, and it has this pincer at the end of a long proboscis, and there's even disagreement about which way is up. But the last thing that the Tully monster could be is a fish."

First discovered back in the 1955 by amateur fossil collector Francis Tully, the creature set off a decades-long investigation into what this bizarre conglomeration of features could actually represent.

"I knew right away. I'd never seen anything like it," Tully said some years after the discovery, adding that after consulting several experts on the matter, he couldn't assign it to any of the major animal groups - a "serious and embarrassing matter".

Researchers had for many years assumed that it was some kind mollusc, like a sea cucumber, or a lobster-like arthropod, and while this explanation held for some time, two papers published in March 2016 (here and here) begged to differ.

A team from Yale University, led by palaeobiologist Victoria McCoy, asserted that the light line running all the way down the creature's middle was not a gut, as previous research had suggested, but a notochord - a skeletal rod that forms the basis of vertebrate backbones.

As Ed Yong explained for The Atlantic last year, the notochord is a key feature of chordates - a vast group of vertebrate animals that includes fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals.

The team also found evidence of gill pouches in a few of the 1,200 or so specimens they analysed, which made them appear more 'fish-like' than previous studies had suggested.

They said this feature was likely missed by other researchers because, for some reason, these creatures tended to die on their fronts and backs instead of their sides - "a position that obscured their gills as they turned to stone", says Yong.

A second study led by researchers at the University of Leicester in the UK also came to the conclusion that the Tully monster was a vertebrate, after scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of its eyes revealed structures called melanosomes.

The team argued that this meant the creature had complex eyes, and said this made it more likely that it was a vertebrate.

But now Sallan and her colleagues say they actually got the whole thing wrong.

"It's important to incorporate all lines of evidence when considering enigmatic fossils: anatomical, preservational and comparative," one of the team, Sam Giles from the University of Oxford in the UK, says in a press statement.

"Applying that standard to the Tully monster argues strongly against a vertebrate identity."

The researchers argue that the Yale team's conclusions are based on a misunderstanding of how creatures fossilise on the ocean floor - you generally see soft tissues preserved, and not internal structures like a notochord.

"In the marine rocks you just see soft tissues, you don't see much internal structure preserved," says Sallan.

The team also argues that having melanosomes in its eyes - structures that produce and store melanin - isn't sufficient evidence to call the Tully monster a vertebrate either, because plenty of invertebrates evolved to have extraordinarily complex eyes.

And when they examined these fossilised eyes for themselves, they concluded that they're 'cup eyes' - fairly simple structures without a lens.

"Eyes have evolved dozens of times. It's not too much of a leap to imagine Tully monsters could have evolved an eye that resembled a vertebrate eye," says Sallan.

"So the problem is, if it does have cup eyes, then it can't be a vertebrate, because all vertebrates either have more complex eyes than that or they secondarily lost them. But lots of other things have cup eyes, like primitive chordates, molluscs and certain types of worms."

This time around, the researchers are bringing more questions than answers, because while they're sure that the Tully monster is not a vertebrate, they're not ready to say what it could be instead.

And while we should keep in mind that this study is just one team's interpretation against another's, it's important in science that the evidence be definitive before we jump to any conclusions.

"Having this kind of misassignment really affects our understanding of vertebrate evolution and vertebrate diversity at this given time," says Sallan.

"It makes it harder to get at how things are changing in response to an ecosystem if you have this outlier. And though of course there are outliers in the fossil record - there are plenty of weird things and that's great - if you're going to make extraordinary claims, you need extraordinary evidence."

The study has been published in Palaeontology.