A simple blood test could one day diagnose a rare inherited form of Alzheimer's disease, decades before symptoms of memory loss even appear.

Researchers in Europe and the United Kingdom have now shown that cases of early-onset Alzheimer's are associated with increasing levels of a biomarker in blood plasma.

Alzheimer's is a generalized term for forms of dementia that have a wide variety of fundamental causes, many of which we're still working out.

One form, called autosomal dominant familial Alzheimer's disease (ADAD), is defined by the presence of mutations in one of several specific genes.

While it covers less than 1 percent of all Alzheimer's cases, symptoms develop significantly sooner in life than with other forms, making it a serious concern for those at risk.

Currently, there are three known single gene mutations associated with early-onset ADAD. As a dominant trait inherited on non-sex chromosomes, a child has a 50 percent chance of inheriting the mutated version of the gene if one parent has the disease.

Genetic testing for the disease can be expensive and a challenge for many to access, so a person whose parent had ADAD usually has to wait and see if they develop the disease themselves.

A blood test that could cheaply and easily diagnose ADAD could put many minds at ease, while also allowing early treatment to stall the progression of the disease where it is detected.

Alzheimer's disease currently has no known cause or cure, and that's part of what makes it so difficult to diagnose. Biological changes ramp up in the background for years before they have any clear physiological effects.

Researchers around the world have been working to develop a proper diagnostic test, but knowing exactly what to target for a clear diagnosis isn't straight-forward. Because Alzheimer's isn't necessarily caused by a single biological pathway, we would need a bunch of different tests for different biomarkers to cover all the bases.

The new study from Sweden provides evidence of a new emerging biomarker. The findings are based on a study in Sweden that followed 33 genetic mutation carriers at risk of ADAD from 1994 to 2018.

Compared to 42 of their relatives without a mutation, the authors noticed three biomarkers that were closely associated with ADAD: plasma phosphorylated tau (P-tau181), neurofilament light chain (NfL), and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP).

All three are potential biomarkers of the disease, but the changes to GFAP were noticed in blood plasma well before P-tau181 or NfL, about 10 years before any symptoms were estimated to begin.

What's more, GFAP showed up in blood plasma samples long before clumps of tau proteins did, and these are a major hallmark of the disease, thought to be present from the very earliest stages. In the past, tau proteins have been used to predict the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease with 90 percent accuracy.

"This is the first report suggesting that plasma GFAP is one of the earliest blood-based biomarkers in ADAD to our knowledge," the authors of the study write.

"Our results suggest that plasma GFAP might reflect Alzheimer's disease pathology upstream to accumulation of tangles and neurodegeneration."

The findings will need to be replicated among larger cohorts, but the authors suspect there is a link between plasma GFAP and brain inflammation.

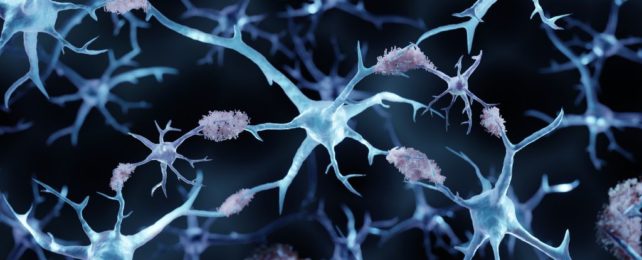

GFAP is a protein for a type of neuron called an astrocyte, which releases pro-inflammatory molecules when it encounters amyloid beta plaques in the brain.

Amyloid beta (Aβ) proteins that fold into plaques are another major hallmark of some forms of Alzheimer's disease. In fact, preliminary blood tests have used toxic precursors of Aβ proteins to accurately diagnose the disease years before its first symptoms emerge.

Perhaps GFAP is another route that shows up even earlier in some cases. Maybe the presence of this protein can activate astrocyte activity, researchers suggest, leading to more Aβ plaques.

To be clear, Aβ plaques and tau clumps on their own may not be toxic. That said, they could be a sign of underlying toxic behavior among other molecules, like GFAP.

The closer we get to the root of the disease, the better chance we have of diagnosing Alzheimer's the moment it shows up, as opposed to after death, which is currently the only conclusive way.

"Our results suggest that GFAP, a presumed biomarker for activated immune cells in the brain, reflects changes in the brain due to Alzheimer disease that occur before the accumulation of tau protein and measurable neuronal damage," says neurobiologist Charlotte Johansson from the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden.

"In the future it could be used as a non-invasive biomarker for the early activation of immune cells such as astrocytes in the central nervous system, which can be valuable to the development of new drugs and to the diagnostics of cognitive diseases."

The study was published in Brain.