Velociraptor has a new cousin, which may have been even more deadly. The new species has been named Shri rapax, and unlike its famous relative it appears to have brandished killer claws on its oversized hands.

The movies may have vastly exaggerated Velociraptor's size – it was closer to a turkey than a human – but one thing they did get right was the weapon of choice: a large, cruelly curved claw on the toe.

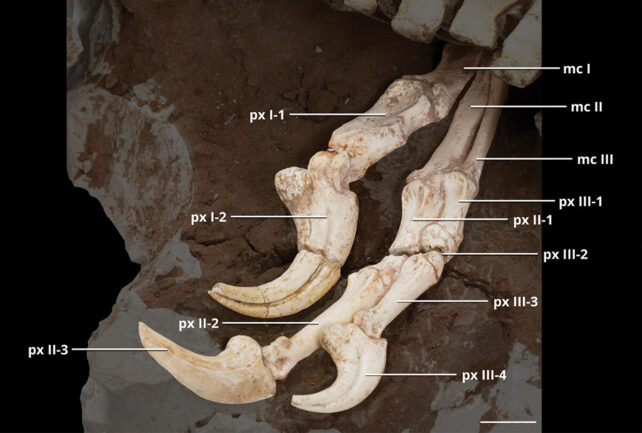

The new species, S. rapax, was a similar size but seemed to focus its strength into its upper body. Its hands were much bulkier – especially the thumb, where prominent bone structures "suggest the tight anchoring of well-developed flexor muscles", the researchers write.

Related: What Would Dinosaurs Look Like Today If They Never Went Extinct?

Capped off with an almost 8-centimeter-long claw that was twice as long as those used by its similar-sized relatives, the dinosaur's thumb would have been perfect for slashing and stabbing.

Although the two dinosaur species were similar, their differences could have helped them live side by side by letting them focus on different types of prey.

"The more robust proportions of [Shri's] hands imply that it was better adapted to target larger and more robust prey than those usually preyed on by Velociraptor," the researchers write. This could have included protoceratopsians or young armored ankylosaurs.

S. rapax also brandished a broader snout, giving it a stronger bite than related raptors, the team says.

No feet were found on the specimen, but it probably still had those iconic claws there too, based on its family tree.

Even in death, the S. rapax has had a hard life. The holotype fossil was poached after its discovery in Mongolia, eventually ending up in private collections in Japan then England, before being bought by a French museum, and finally returned to Mongolia.

The skull and neck bones were removed to be scanned and studied in Belgium, but have since gone missing. The skeleton is now donning a printed cast of the skull, based on data from that scan.

The research was published in the journal Historical Biology.