In 2015, paleontologists announced a stunning discovery. Preserved in Cretaceous rock from Brazil was the complete skeleton of a beast resembling a snake, but with one significant addition: four tiny, almost vestigial legs.

This marked something of a paleontological 'holy grail'. The beast, which they named Tetrapodophis amplectus, was the missing link between snakes and lizards.

There's just one problem. According to a new analysis of the remains, Tetrapodophis (from the Greek, meaning "four-legged snake") is not a snake at all, but a species of extinct marine lizard that lived over 110 million years ago.

"There are many evolutionary questions that could be answered by finding a four-legged snake fossil, but only if it is the real deal," says paleontologist Michael Caldwell of the University of Alberta in Canada.

"The major conclusion of our team is that Tetrapodophis amplectus is not in fact a snake and was misclassified. Rather, all aspects of its anatomy are consistent with the anatomy observed in a group of extinct marine lizards from the Cretaceous period known as dolichosaurs."

It's long been accepted that snakes weren't always the limbless slitherers they are today. We even have other fossils attesting to this, such as Najash rionegrina, a serpent from around 95 million years ago sporting two rear limbs, discovered in 2006.

The fossil record, paleontologists expected, ought to contain a four-limbed snake somewhere in the dim corridors of time.

Tetrapodophis amplectus looked like a very promising candidate. The 2015 study thoroughly examined and analyzed the creature's bones, but very quickly, Caldwell thought something was amiss. He and his colleagues presented a rebuttal in October 2016 at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting.

After examining the skeleton, they found that the teeth were not hooked or oriented like a snake's teeth, and its skull and skeleton were not like those of a snake. The team also couldn't see the large ventral scales that would have helped mark it as a snake.

What's more, in its belly were the remains of one of its last meals, appearing to be fishbones – consistent with an aquatic creature.

The new research goes even more in depth, picking up on something the original 2015 study missed entirely: the stone in which the skeleton was encased.

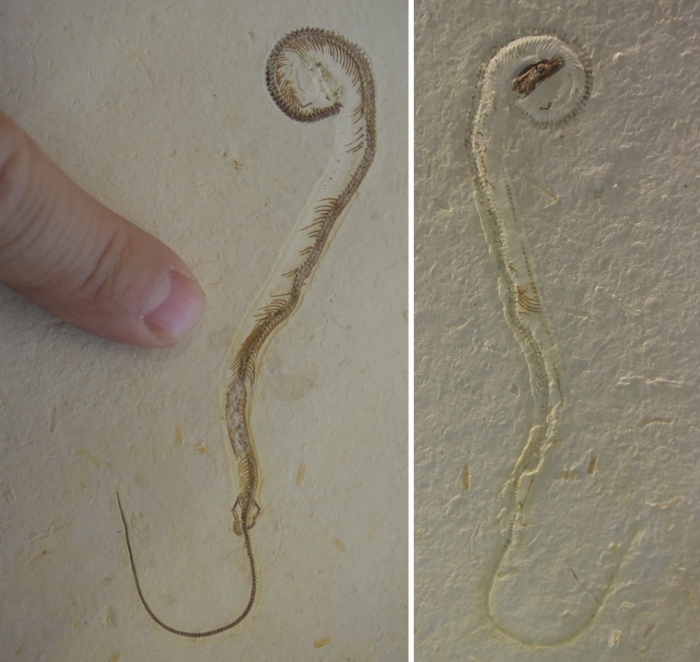

The skeleton of Tetrapodophis and the mold of its skeleton left in the rock. (Michael Caldwell)

The skeleton of Tetrapodophis and the mold of its skeleton left in the rock. (Michael Caldwell)

"When the rock containing the specimen was split and it was discovered, the skeleton and skull ended up on opposite sides of the slab, with a natural mould preserving the shape of each on the opposite side," Caldwell says.

"The original study only described the skull and overlooked the natural mould, which preserved several features that make it clear that Tetrapodophis did not have the skull of a snake – not even of a primitive one."

The paleontologists behind the original claims of Tetraphodis's serpent membership stood by their observations in the wake of the 2016 criticisms. Now that both studies are a part of the literature, it'll be up to future researchers to come down on either side of the debate.

Even if it's not a snake, however, the perhaps now misnamed Tetrapodophis still has a lot to teach us. The tiny skeleton is exquisitely preserved, which is an absolute gift for studies on dolichosaurs. But only if access can be obtained. Currently, the specimen is in private hands, in contravention of Brazilian law.

"There were no appropriate permits for the specimen's original removal from Brazil and, since its original publication, it has been housed in a private collection with limited access to researchers. The situation was met with a large backlash from the scientific community," says paleontologist Tiago Simões of Harvard University.

"In our redescription of Tetrapodophis, we lay out the important legal status of the specimen and emphasize the necessity of its repatriation to Brazil, in accordance not only with Brazilian legislation but also international treaties and the increasing international effort to reduce the impact of colonialist practices in science."

The team's research has been published in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.