Bacteria perform some dramatic defensive shapeshifting up in space to guard against killer antibiotics, new research has found, giving us fresh insight into how these microorganisms can survive and even flourish once they're outside Earth's orbit.

We already know bacteria behave differently in space, and understanding how and why that happens is crucial if we want to keep our astronauts safe on long-distance journeys – and protect the planets we're heading for as well.

In an experiment planned by researchers at the University of Colorado at Boulder and carried out on the ISS, cultures of Escherichia coli bacteria were doused with the antibiotic gentamicin sulphate, which usually kills off E. coli quite easily. Out in space, it was a totally different story.

"We knew bacteria behave differently in space and that it takes higher concentrations of antibiotics to kill them," says one of the researchers, Luis Zea.

"What's new is that we conducted a systematic analysis of the changing physical appearance of the bacteria during the experiments."

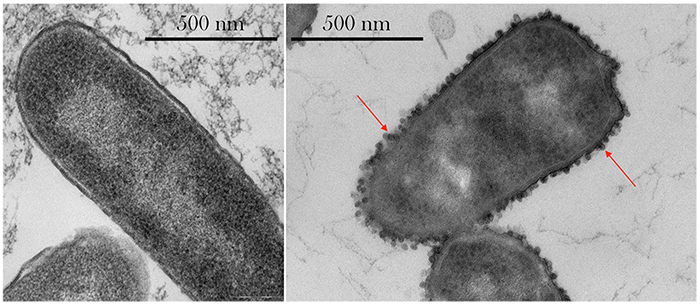

The space bacteria (right) developed extra vesicles. Credit: UC Boulder

The space bacteria (right) developed extra vesicles. Credit: UC Boulder

And what a change. When exposed to gentamicin sulphate, the E. coli reacted with a 13-fold increase in cell numbers and a 73 percent reduction in cell volume size.

That's compared against a control group of E. coli treated with the same levels of gentamicin sulphate here on Earth.

The researchers say that due to the lack of gravity in the ISS, the bacteria have a much smaller surface area available for the drugs to interact with.

What's more, the bacteria threw up extra shields by thickening their cell walls and outer membranes, and growing in clumps so a shell of outer cells could protect the inner ones from getting exposed.

The scientists also spotted a greater number of tiny capsules called membrane vesicles, used as messengers for bacteria cells to initiate infections.

"Both the increase in cell envelope thickness and in the outer membrane vesicles may be indicative of drug resistance mechanisms being activated in the spaceflight samples," says Zea.

"And this experiment and others like it give us the opportunity to better understand how bacteria become resistant to antibiotics here on Earth."

NASA astronaut Rick Mastracchio supervised the experiment on the ISS. Credit: NASA

NASA astronaut Rick Mastracchio supervised the experiment on the ISS. Credit: NASA

As well as helping us understand normal bacterial resistance better, as Zea points out, the ISS experiments will be helpful if these supercharged strains of bacteria should ever make it back down to Earth somehow – just try not to think about that while you're dropping off to sleep tonight.

There's a lot of research still to do, but these are important clues for figuring out how a lack of gravity and the absence of an atmosphere affects bacteria.

Astronauts already have to deal with rapidly growing biofilms on equipment out in space, and if someone gets infected on a mission to Mars, we need to know how to deal with it. On the positive side, these hardy microorganisms could also give us some ideas about kickstarting life on distant planets.

Right now it's not clear why some bacteria prefer being up in space or are better able to defend themselves, but we're getting closer to finding out – and you can bet there'll be plenty more similar experiments to follow.

"The low gravity of space provides a unique test bed for developing new techniques, products and processes that can benefit not only astronauts, but also people on Earth," says one of the team, Louis Stodieck, also from the University of Colorado.

The findings have been published in Frontiers in Microbiology.