Archaeologists at the British Museum have accurately reconstructed the face of a man who lived 9,500 years ago in the ancient city of Jericho, allowing us to actually see what he looked like for the first time.

The reconstruction was done using plaster after a CT scan revealed new details about his skull. Known as the Jericho Skull, it was found in the region that used to be Jericho - now the West Bank region of Palestine - in 1953.

While the man's true identity is unknown, the team thinks the man was someone of great importance in his day, based on the amount of care people took to fill his skull with plaster when he was buried.

Though that seems odd, plastered skulls are an early form of ritual burial. The practice involved removing the skull from the deceased person's corpse, filling it with plaster, then decorating it by adding a layer of paint and inserting shells into the eye sockets.

These remains were then likely displayed while the rest of the body was buried under the family's home, a tradition that was very common way back in 8200-7500 BCE.

The Jericho Skull was found buried alongside several other plastered skulls, but is the best known of the remains because of how well preserved it is.

It's thought to be one of the best examples of these early burial practices, though not much more about the man is truly known. It is, after all, 9,500 years old.

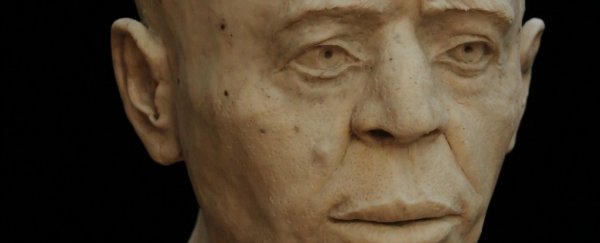

Here's what it looked like before the reconstruction:

Trustees of the British Museum

Trustees of the British Museum

"He was certainly a mature individual when he died, but we cannot say exactly why his skull, or for that matter the other skulls that were buried alongside him, were chosen to be plastered," curator Alexandra Fletcher, from the British Museum, told Jen Viegas at Seeker.

"It may have been something these individuals achieved in life that led to them being remembered after death."

To better understand the practice, researchers sent the skull to be scanned at the Imaging and Analysis Centre at the Natural History Museum, where a complete micro-CT scan revealed a ton of new details and allowed researchers to create a 3D model as well.

According to Viegas, the team found that the skull was a missing a jaw under the plaster, he had decaying teeth (from what they saw on the upper section of his mouth), he suffered a broken nose at some point in his life, and he also shows signs of head binding - a practice where the head is artificially shaped in infancy to elongate it.

"Head binding is something that many different peoples have undertaken in various forms around the world until very recently," Fletcher told Seeker.

"In this case, the bindings have made the top and back of the head broader - different from other practices that aim for an elongated shape. I think this was regarded as a 'good look' in Jericho at this time."

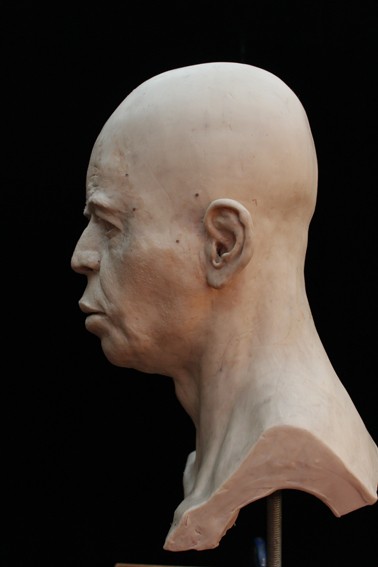

The team then was able to create a very accurate reconstruction of the man's face from all of these newly gathered details, providing a new way to see what the man might have actually looked like. Here's what they reconstructed:

Trustees of the British Museum

Trustees of the British Museum

While the new details have definitely provided insights into what the man looked like, there's still a lot of work to be done if the team ever hopes to fully understand the culture that he came from.

One of the best bets is to hopefully gather information from a DNA sample, though the process used to potentially gather that DNA could damage the skull and isn't guaranteed to yield any results.

"If we were able to extract DNA from the human remains beneath the plaster, there is currently a very slight chance that we would be able to find out this individual's hair and eye colour," Fletcher explained.

"I say a slight chance because the DNA preservation in such ancient human remains can be too poor to obtain any information."

The hope is that a new option will present itself in the future, allowing the team to understand more about the man. Until then, though, we at least have a new way of seeing him.

Reconstructed faces are becoming more popular as scanning technologies continue to become better. Earlier this year, researchers from the University of Melbourne in Australia reconstructed the face of a 2,300-year-old Egyptian mummy.

You can check out the newly created reconstruction yourself at the British Museum, where it will be on display from mid-December to mid-February.