A toxic antibody is the latest weapon to show promise as a broad spectrum treatment for multiple forms of advanced cancer.

Dubbed a 'Trojan horse' approach to chemotherapy, the new drug has proven itself worthy of moving up the chain of clinical trials to being tested on a greater variety of patients. It's not a fabled cure-all, but this approach might be as close as we're going to get.

Researchers from The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust tested the new treatment in a clinical trial involving 147 patients to evaluate its potential benefits and risks of side effects.

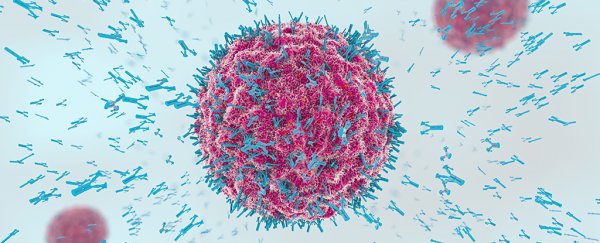

Called tisotumab vedotin, or simply TV for short, the drug is made up of a monoclonal antibody, and a cytotoxic component which can fatally damage cells.

The antibody, if you like, is the spectacular gift horse at the enemy's door - it seeks out cell-signalling flags in membranes called tissue factors and demands entry.

While all kinds of healthy cells have this factor, a wide variety of tumours exploit it as a way to grow out of control, making it an appealing target for the cytotoxic seek-and-destroy chemical weapon.

In this case, the component tasked with this murderous job is monomethyl auristatin E, a molecule that prevents cells from reproducing.

"What is so exciting about this treatment is that its mechanism of action is completely novel – it acts like a Trojan horse to sneak into cancer cells and kill them from the inside," says oncologist Johann de Bono from The Institute of Cancer Research.

"Our early study shows that it has the potential to treat a large number of different types of cancer, and particularly some of those with very poor survival rates."

Those included cancer of the cervix, bladder, ovaries, endometrium, oesophagus, and lung.

Those with bladder cancer saw the most impressive response, with 27 percent of enrolled volunteers seeing their disease stabilise. At the other end was endometrial cancer, with a more modest 7 percent of subjects improving.

"It's exciting to see the potential shown by TV across a range of hard-to-treat cancers," says The Institute of Cancer Research's Chief Executive, Paul Workman.

"I look forward to seeing it progress in the clinic and hope it can benefit patients who currently have run out of treatment options."

That progress is slow going. Phase I clinical trials began in 2013 with the testing of TV's safety on just 27 patients.

A year and a half later, serious health concerns had emerged, including signs of severe type 2 diabetes, inflammation of the mucosa, and fever.

Lower doses saw these more concerning side-effects diminish, though the treatment was still far from problem-free, with nosebleeds, nausea, and fatigue among common complaints.

Still, when it's a question of life or death, non-fatal ailments such as these can seem trivial by comparison. Phase I testing gave way into phase II, which showed TV could make a big difference to a lot of patients with cancers little else will treat.

"TV has manageable side effects, and we saw some good responses in the patients in our trial, all of whom had late-stage cancer that had been heavily pre-treated with other drugs and who had run out of other options," says de Bono.

The next step is to expand phase II testing to include cancers of the bowel and pancreas, while testing it as a second-line drug for cervical cancers that have failed to perish following initial treatments.

It's important to note that this isn't a panacea, or the end of cancer as we know it. But when so many promising treatments fail to make it beyond the starting line, seeing promise in one that could make a difference to a wide variety of advanced cancers is exciting.

If all goes well, we might expect a third phase of testing in several years, where the drug's efficacy and safety is compared with similar treatments.

This all takes time and money, so we can't expect TV to become available for some time yet (if at all). But the demonstrated success of an age-old military strategy applied in an anti-cancer drug bodes well for treatments of its type.

"We desperately need innovative treatments like this one that can attack cancers in brand new ways, and remain effective even against tumours that have become resistant to standard therapies," says Workman.

This research was published in The Lancet Oncology.