There's a mystery lurking in the Pacific Ocean just off the coast of Big Sur, California. An underwater survey has found thousands of small, round divots scooped out of the soft sediment on the seafloor.

While it's not clear how the holes formed, they seem to have quickly become popular among seafloor critters as desirable shelters.

Researchers at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) found roughly 15,000 of these holes, averaging 11 metres (36 feet) in diameter and one metre (3 feet) in depth.

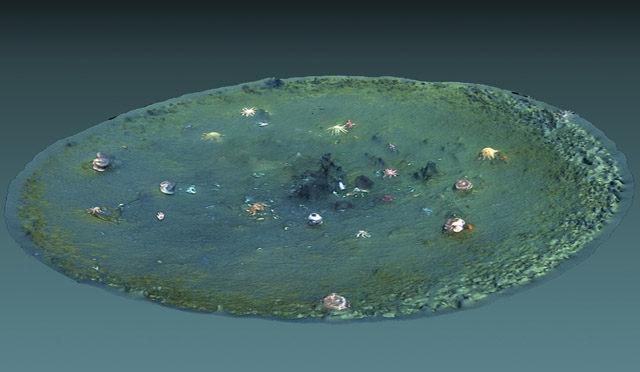

Computer-generated 3D view of a micro-depression. (Ben Erwin © 2019 MBARI)

Computer-generated 3D view of a micro-depression. (Ben Erwin © 2019 MBARI)

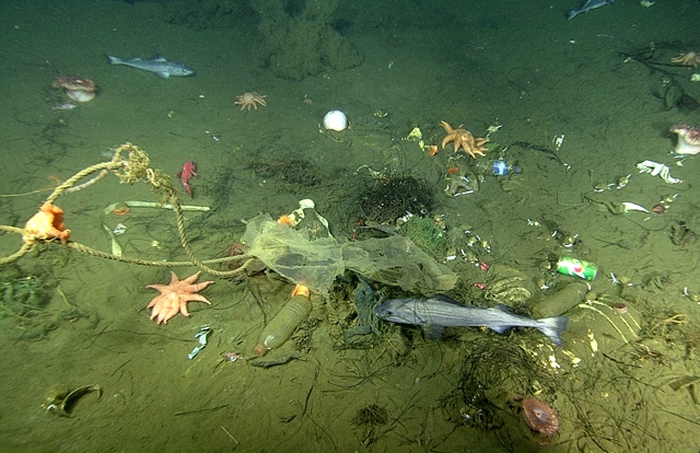

Thirty percent of these indentations were found to contain human garbage, along with fish and other marine beasties using that garbage as a habitat.

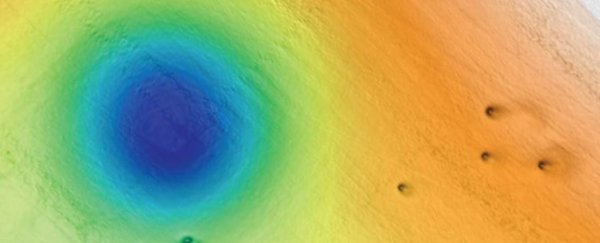

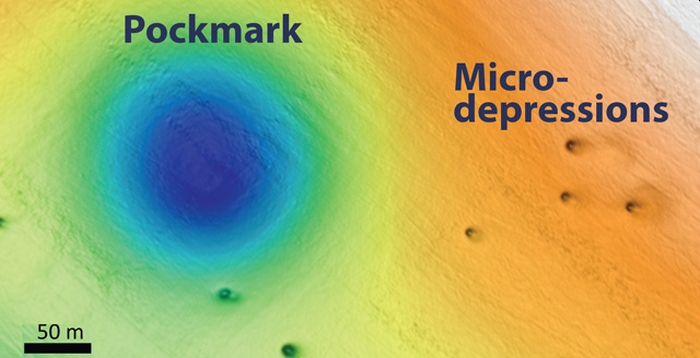

The discovery was made as part of a survey to study underwater features called pockmarks. These are also depressions in the seafloor, but they're somewhat bigger, averaging 175 metres (574 feet) across and five metres (16 feet) deep.

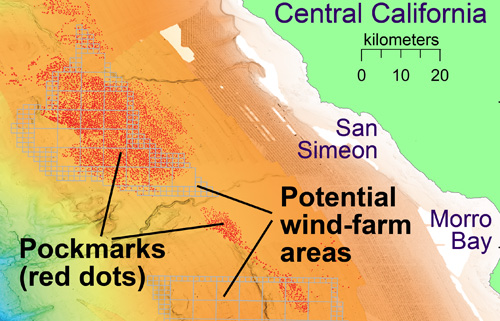

(© MBARI)

(© MBARI)

These pockmarks show up on ship-mounted sonar, so they've been known about since a 1999 sonar survey; there are over 5,200 of them spread out over 1,300 square kilometres (500 square miles) of seafloor near Big Sur. What causes them is also unknown; and, since the area is being considered for an offshore wind farm, further investigation was required.

If, for instance, the holes are caused by gases such as methane under the seafloor bubbling out and leaving a depression in their wake - one of the leading theories - that could affect the placement of wind turbines.

So, the MBARI team set their autonomous underwater vehicles, equipped with sonar devices, to work. They found no evidence of methane; in fact, it seems the pockmarks have been inactive for over 50,000 years.

(© 2019 MBARI)

(© 2019 MBARI)

But, in the data returned by the robots, the researchers saw other holes, too small to be picked up by ship-mounted sonar, but clearly visible now. So, they sent in remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) equipped with cameras for a closer look.

The team calls the holes 'micro-depressions' (to differentiate from the larger pockmarks). These micro-depressions appear to be much younger than the pockmarks, and they have steeper sides. They also have "tails" of sediment, which seem to be oriented in the same direction in many areas.

In addition to the garbage found in these depressions, 20 percent contained other things - stones, kelp holdfasts, and a whale skull - but the sediment around the holes was empty.

The team also thinks that the animals taking up residence in the garbage could be helping to carve the micro-depressions out even deeper.

(MBARI)

(MBARI)

"The objects observed within micro-depressions, such as trash and rocks, are hypothesised to have been rafted out in kelp holdfasts or dropped over the side of a boat," the researchers write in their abstract.

"The presence of these objects provides micro habitats for fish, that were commonly observed in ROV dives stirring up the fine-grained sediment, which is then carried away by sea-bottom currents, further contributing to carving out the eroded hole(s) left behind. These observations imply that marine trash is at least partly responsible for approximately 4,500 of the 15,000 MDs and provide some clues as to how the micro-depressions are created."

To reconstruct the potential sequence events, it might go a bit like this: something - whether it be a whale skull or a small collection of garbage - sits on the seafloor. Marine life moves in and makes itself at home; their motion kicks the sediment up and out, digging a little divot in the seafloor.

It's just a hypothesis, and doesn't account for the micro-depressions that don't seem to have any objects in them. But, according to the researchers, we know that the micro-depressions are not baby pockmarks, because they're morphologically distinct from the larger holes. In addition, they found no evidence of sub-seafloor gas activity.

"Overall, a lot more work needs to be done to understand how all these features were formed, and this work is in progress," MBARI marine scientist Eve Lundsten said.

The research was presented at the 2019 Fall Meeting of the American Geophysical Union.