The idea of evolution backtracking isn't a completely new idea, but catching it in action isn't an everyday experience.

A newly documented example of wild growing tomatoes on the black rocks of the Galapagos Islands gives researchers a prime example of a species adapting by rolling back genetic changes put in place over several million years.

Researchers from the University of California, Riverside (UC Riverside) and the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel say it's evidence that species can wind back changes that have happened through evolution.

Related: Ferns Can Evolve Backwards, Challenging a Common Assumption on Life

"It's not something we usually expect," says molecular biochemist Adam Jozwiak, from UC Riverside. "But here it is, happening in real time, on a volcanic island."

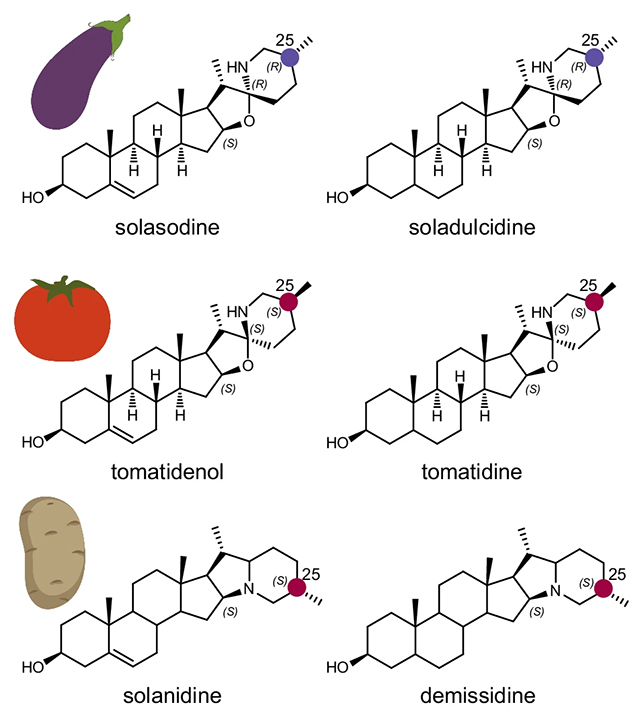

Through an analysis of 56 tomato samples taken from the Galapagos, covering both the Solanum cheesmaniae and Solanum galapagense species, the team looked at the production of alkaloids in the plants: toxic chemicals intended to put off predators.

In the case of the S. cheesmaniae tomatoes, different alkaloids were found in different parts of the islands. On the eastern islands, the plants come with alkaloids in a form comparable to those in the cultivated fruit from the rest of the world; but to the west, an older, more ancestral form of the chemicals were found.

This older version of the alkaloid matches the one found in eggplant relatives of the tomato stretching back millions of years.

Through further lab tests and modeling, the researchers identified a particular enzyme as being responsible for this alkaloid production and confirmed its ancient roots. A change in just a few amino acids was enough to flip the switch on the alkaloid production, the researchers determined.

There are other isolated examples of evolutionary backflips known scientifically as genetic atavisms, where a mutation causes a species to revert to expressing an ancestral trait. These include experiments on chickens that have been genetically tweaked to revive their ancient programming for growing teeth.

The difference in this case is a critical change has propagated through entire populations. In some plants, multiple genes have reverted, suggesting strong selection pressures are involved.

What makes it an even more interesting shift is that the western parts of the Galapagos islands are younger – less than half a million years old – and more barren. It seems environmental pressures may have driven these steps back into evolutionary history.

Besides being a fascinating example of how evolution turns around on itself, the research also opens up possibilities for advanced genetic engineering that works with even greater control, altering plant chemistry for multiple benefits.

"If you change just a few amino acids, you can get a completely different molecule," says Jozwiak. "That knowledge could help us engineer new medicines, design better pest resistance, or even make less toxic produce."

"But first, we have to understand how nature does it. This study is one step toward that."

The research has been published in Nature Communications.