As macabre as it seems, it's not exactly a secret that in some species of shark the unborn dine on their siblings while still developing in the womb.

But it turns out we don't know the half of it. A novel kind of ultrasound device has provided biologists with a detailed view of this common act of cannibalism, and in 2018 it revealed they don't just nibble on their neighbour. Embryos will travel between wombs to feast.

No, that's not a typo. Many species of shark mature their eggs or gestate embryos in a left and a right uterus.

For most animals, embryonic movement is rather limited to a bit of squirming and the occasional flip. Even for young that aren't anchored to a placenta, gestation is thought to be a rather sedentary affair.

So researchers from Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium in Motobu, Japan, were surprised to find the unborn pups of captive tawny nurse sharks (Nebrius ferrugineus) not only moving around their own uterus, but moving house altogether.

"Our data shows frequent embryonic migration between the right and left uteri, which is contradictory to the "sedentary" mammalian fetus," the team wrote in their 2018 report.

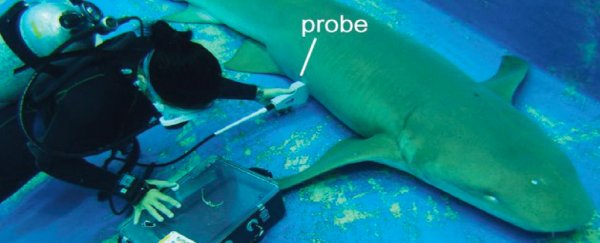

The discovery came courtesy of a fancy new piece of equipment that allows the kind of ultrasound device you'd use to scan a human pregnancy to be packed up and carried underwater.

Portable scanners have been in use for a few years, and even used to look inside sharks. But a shark mother out of water isn't exactly at her relaxed best.

To study specimens in a more natural state, the team had to make it water- and pressure resistant.

Over several years, the researchers studied a trio of pregnant tawny nurse sharks on display in an aquarium exhibition tank, capturing more than 40 ultrasound clips.

The results provided a family album on a time line, where up to four pups could be seen wiggling about inside each mother.

In one mother, embryos swapped sides three times. In another, the movement was far more extreme – a total of 24 migrations were recorded across the duration of the pregnancy.

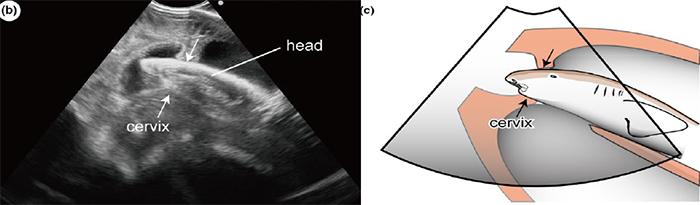

One of the scans showed the actual room swap taking place, showing an embryo hurriedly pushing its way from one uterus to the other.

We're not talking a leisurely stroll here either. The pup swam at a speedy eight centimetres per second.

One of the female sharks started her pregnancy with two pups in each uterus. After some back and forth, four soon became three. Just under two months later, there were two.

By the end of the gestation just a single, no doubt smugly satisfied, winner remained.

Biologists have had their suspicions that the embryos of sharks could move between uteruses and gobble up their competition. In 1993, footage shot for a Discovery Channel program showed a similar embryonic migration inside a sand tiger shark (Carcharias taurus).

Yet the observations were made during an invasive surgical procedure, leaving open the question of whether such a behaviour occurred under less stressful conditions.

Other studies have indicated the cervix of some shark species might not remain as watertight as it does in other animals.

With these new observations, it seems the cervix doesn't just sometimes leak in a bit of water. It can open wide enough for embryos to poke their heads out for a sniff.

(Tomita etal/Ethology)

(Tomita etal/Ethology)

(We apologise to all pregnant mothers for that bit of nightmare fuel.)

It's not clear if the gestating offspring of other species of shark display this kind of migratory 'dining out' behaviour.

Several species have been studied under natural conditions, but the only embryonic movement researchers noticed were restricted to the opening and closing of their mouths, most likely to assist in respiration.

The researchers think this potentially unique behaviour might come down to the way aplacental tawny nurse and sand tiger sharks feed their developing embryos.

Without yolks of a placenta to sustain them, developing pups in many shark species will diet on surplus eggs. Not to mention the occasional sibling or two.

"It seems likely that in this mode of reproduction, the active swimming ability of the embryo may allow it to effectively search and capture nutritive eggs in the uterine environment," the researchers conclude.

Just when we thought sharks couldn't be any more awesome.

This research was published in Ethology.

A version of this article was first published in December 2018.