A world infamous for its hellacious conditions may have just been seen spotting one of the prettiest phenomena ever to grace Earth's own atmosphere.

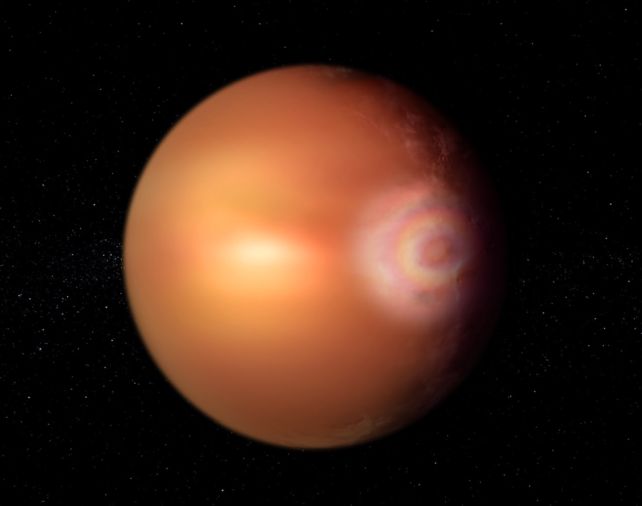

High up in the metal-filled skies of a world named WASP-76b, astronomers have found evidence of a shimmering, multi-hued halo of light known as a glory. This spectacle has never before been seen outside of the Solar System, and within it, only on two worlds: Earth (of course) and Venus.

Consisting of a series of concentric rings around a bright center, these gorgeous displays of color require specific conditions to form. Light needs to shine on a mist of spherical droplets that are all more or less the same size.

Its appearance on WASP-76b can therefore tell us something about the mysterious atmosphere of this very alien world.

"There's a reason no glory has been seen before outside our Solar System – it requires very peculiar conditions," says astronomer Olivier Demangeon, of the Institute of Astrophysics and Space Sciences in Portugal.

"First, you need atmospheric particles that are close-to-perfectly spherical, completely uniform and stable enough to be observed over a long time. The planet's nearby star needs to shine directly at it, with the observer – here Cheops – at just the right orientation."

WASP-76b is a favorite for planetary scientists. It orbits a yellow-white star a little bigger than the Sun in the constellation of Pisces, some 640 light-years from Earth. Its orbit around the star is incredibly tight, whipping around in just 1.8 days. That closeness means it's also incredibly hot, with dayside temperatures exceeding 2,400 degrees Celsius (4,350 Fahrenheit) being hot enough to vaporize iron.

And iron there is. There are literally clouds of the element in the exoplanet's puffy atmosphere. WASP-76b is 90 percent of the mass of Jupiter, but around 185 percent of its size.

As the planet passes in front of its star, astronomers are able to peer into its atmosphere. So far, in addition to iron, they've identified sodium, calcium, chromium, lithium, hydrogen, vanadium, magnesium, nitrogen, manganese, potassium, and barium.

It's one of the most looked-at worlds in the galaxy. And in all this peering, astronomers have noticed something strange about the exoplanet's brightness. In data collected by the European Space Agency's ESA's CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite (Cheops), researchers noticed an excess in brightness in the eastern terminator, the line that marks the boundary between night and day.

"This is the first time that such a sharp change has been detected in the brightness of an exoplanet," Olivier says. "This discovery leads us to hypothesize that this unexpected glow could be caused by a strong, localized, and anisotropic (directionally dependent) reflection – the glory effect."

The signal is very faint, and further work will be needed to confirm that a glory is indeed what we are looking at on WASP-76b. However, if it is, that will reveal something new about the composition of the exoplanet's upper atmosphere.

With the effect being analyzed across 23 observations in three years, it's clear the spherical aerosol droplets must be consistently present in the exoplanet's clouds or replenished at a constant rate. This, in turn, requires stable long-term temperature conditions in the atmosphere of WASP-76b.

If the phenomenon does turn out to be an enormous glory, scientists will need to model the world's atmosphere to work out what conditions support its presence.

The discovery could have more far-reaching implications, too. Positively identifying a glory on WASP-76b would give scientists a blueprint to search for the same phenomenon on other exoplanets. And being able to narrow down changes in light could lead to the discovery of other features, such as starlight glinting off liquid oceans and lakes, the way sunlight gleams on Earth's oceans.

Future observations are being planned so that we can find out.

The research has been published in Astronomy & Astrophysics.