After six years of searching, researchers from the University of Basel and ETH Zurich in Switzerland have found what might be a crucial weapon in the fight against superbugs: viruses that are able to prey on and kill dangerous bacteria while they're in a dormant state.

Bacteria go into this sleep mode when they're low on nutrients or under various kinds of stress. It's a form of self-protection, which means the bacteria can't spread or grow. Yet existing in a shut-down state also protects them from threats that hijack their engines, such as viruses or antibiotics.

Bacteria actually spend a lot of time in this inactive state. Up until now, all efforts to discover a type of bacteria-infecting virus (or bacteriophage) that could wipe out hibernating bacteria had been unsuccessful.

"In view of the huge number of bacteriophages, however, I was always convinced that evolution must have produced some that can crack into dormant bacteria," says microbiologist Alexander Harms from the University of Basel.

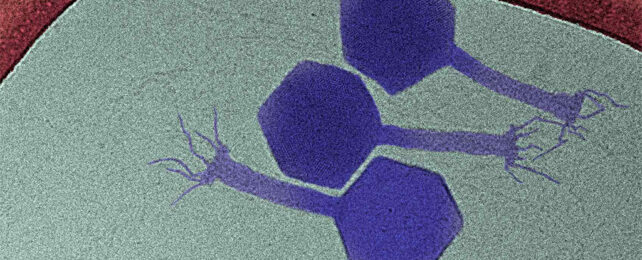

That conviction has now paid off. Harms and his team identified a previously undiscovered phage that they're calling Paride, and which was found on rotting plant material in a Swiss cemetery.

The phage is able to tackle the common bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa, found in a variety of environments including hospitals. If it infects the human body, it can trigger serious respiratory diseases, such as potentially fatal forms of pneumonia.

Crucially, when Paride was combined with the antibiotic meropenem, it was able to kill off 99 percent of P. aeruginosa in lab tests. In experiments on mice, the phage and antibiotic were also effective at destroying bacteria – but only in combination.

"This shows that our discovery is not just a laboratory artifact, but could also be clinically relevant," says microbiologist Enea Maffei from the University of Basel.

With bacteria and the resulting infections becoming increasingly resistant to the drugs we've developed to tackle them, enlisting the help of viruses to batter bugs even when they're in self-protective mode could be a significant breakthrough.

The researchers aren't fully sure how this is working, but it seems as though the virus might be using some kind of molecular key to trick P. aeruginosa and unlock its defenses, which then allows the antibiotic to do its work.

Scientists are becoming increasingly interested in using phages to destroy drug-resistant bacteria – or superbugs – and now we have one that works in a bacteria's dormant stage. However, a lot of study and hard work remains ahead.

"We're just at the beginning," says Harms. "The one thing we know for sure is that we know almost nothing."

The research has been published in Nature Communications.