High-speed video footage has captured for the first time, what US researchers say are hundreds of tiny aerosol particles being released from raindrops when they impact with soil.

The mechanical engineers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), who observed the "frenzied" aerosol release in action, say it could account for the earthy smell that accompanies rain after a long dry spell.

You're probably familiar with the smell in question, and you may have even wondered why it occurs when it rains.

In the 1960s, a pair of Australian scientists began investigating rain's mysterious aroma, and published a paper in Nature in which they coined the term petrichor to describe the scent of rain on dry earth.

As writer Joseph Stromberg explains for Smithsonian.com, the Australian scientists "determined that one of the main causes of this distinctive smell is a blend of oils secreted by some plants during arid periods. When a rainstorm comes after a drought, compounds from the oils—which accumulate over time in dry rocks and soil—are mixed and released into the air."

But mechanical engineer Cullen Buie from MIT said in a press release that the Australians didn't explain "the mechanism for how that smell gets into the air."

"One hypothesis we have is that that smell comes from this mechanism we've discovered," Buie said.

In addition, the researchers suggest that the release of these aerosols could shed light on how microbes and chemicals in the soil can be delivered to the environment, and how they could potentially spread soil-based diseases.

"Until now, people didn't know that aerosols could be generated from raindrops on soil," co-author Youngsoo Joung added. "This finding should be a good reference for future work, illuminating microbes and chemicals existing inside soil and other natural materials, and how they can be delivered in the environment, and possibly to humans."

By understanding how permeable the surface was, as well as the speed and size of the raindrop, the researchers were able to accurately estimate how many aerosols would be generated.

Their results were published last week in Nature Communications.

According to MIT press release, the researchers conducted roughly 600 experiments on 28 types of surfaces: 12 engineered materials and 16 soil samples.

They tested the permeability of the different materials by putting them in long tubes, and timing how long it took for water to seep through. Next they simulated rainfall of different intensities by releasing single drops of water from varying heights (the higher the point of release, the faster the speed).

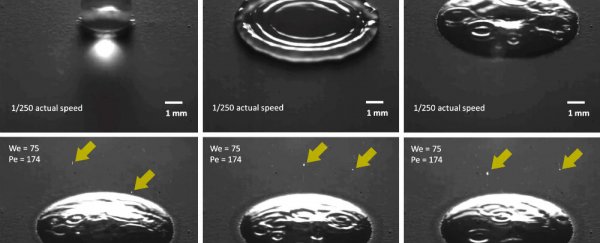

The duo used high-speed cameras to capture the impact, and observed something that was previously unseen. As the raindrop hits the soil, it flattens, and simultaneously, hundreds of aerosol particles rise up and burst through the liquid's skin. And all this happens in just a few microseconds.

The team observed that more aerosols were produced during light rain than heavy rain, and suspect this is because there is more time at impact for the aerosol bubbles to form.

While scientists have long observed that raindrops can trap and release aerosols when falling on water, this paper is the first to show this effect on soil, said James Bird, a mechanical engineer at Boston University, in the MIT press release.

Bird, who was not involved in the research, added: "The aspect of this paper that I find most exciting is that it brings the conversation of bubble-induced aerosol formation from the ocean over to the land. Microbes from soil have been observed high in the atmosphere; this paper provides an elegant mechanism by which these microbes can be propelled past the stagnant layer of air around them to a place where the breeze can take them elsewhere."

Sources: Smithsonian.com, MIT