Researchers from the University College London have developed a way to find unique markings within a tumour, also known as its 'Achilles heel', so that the body can target the disease. The researchers believe that their work could pave way to new treatments for cancer patients and hope to test their method and extend it for widespread use in patients within two years.

The results of their study were published in Science, and the research is funded by the Cancer Research UK.

Though the work is promising, and experts who have weighed in on this work agree that the methods make sense and are sound in theory, it could be very complicated in reality.

Previously, scientists tried to kill cancer tumours through a similar steering of the immune system, but these treatments did not give successful results. Apparently, the teams trained the body's own defences to go after the wrong target.

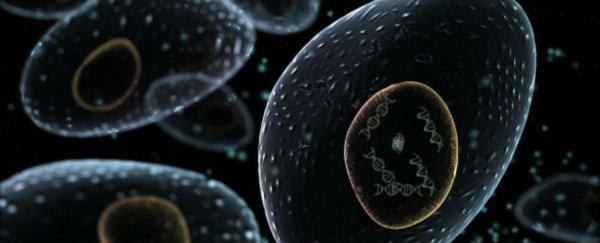

Part of the problem is that cancer cells are not identical at all. Indeed, they have been found to be extremely mutated. They are generally described as being like a tree with 'trunk' mutations, these mutations branch off in different directions, which is known as cancer heterogeneity.

The new study shows a way of discovering the 'trunk' mutations that change antigens, which are proteins that stick out of the surface of cancer cells.

When referencing the work, Charles Swanton, from the UCL Cancer Institute, is hopeful. He states, "This is exciting. Now we can prioritise and target tumour antigens that are present in every cell - the Achilles heel of these highly complex cancers." And adds, "This is really fascinating and takes personalised medicine to its absolute limit, where each patient would have a unique, bespoke treatment."

There are two approaches suggested in relation to how to target these trunk mutations. One is to develop cancer vaccines for each patient that train the immune system to spot them. The second one is to 'fish' for immune cells that already target those mutations and multiply their numbers in the lab, then place them back in the patient's body.

Marco Gerlinger, from the Institute of Cancer Research, notes that the work is interesting, but that it's actual workings have yet to be determined: "Targeting trunk mutations makes sense from many points of view, but it is early days, and whether it's that simple, I'm not entirely sure … Many cancers are not standing still, but they keep evolving constantly. These are moving targets which makes it difficult to get them under control."

Stefan Symeonides, clinician scientist in experimental cancer medicine at the University of Edinburgh, adds that designing a personalised vaccine may be ideal, but is currently impractical, especially when a patient needs treatment straight away. "It's not just the number of antigens, it's how many of the cancer cells have them," he clarifies.

Still, he adds that the potential use of the work is remarkable. "This data will be quoted in discussions for years, as we try to understand which patients benefit from immunotherapy drugs, which ones don't, and why, so we can improve those therapies."

This article was originally published by Futurism. Read the original article.