Despite the long evolutionary history of our species, humans have only been reading and writing for a few thousand years. New research shows that we may have 'recycled' a key region of the brain to help us start making sense of the written word.

In tests on rhesus macaque monkeys, scientists have demonstrated that a region called the inferior temporal (IT) cortex in the primate's brain is capable of providing the essential information we need to turn strings of letters into something more meaningful.

That neural behaviour suggests that, instead of evolving new areas of the brain specifically for reading, human beings may have repurposed the same brain region while developing the ability to recognise words as they were written down – what's known as orthographic processing.

"This work has opened up a potential linkage between our rapidly developing understanding of the neural mechanisms of visual processing and an important primate behaviour – human reading," says neuroscientist James DiCarlo from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

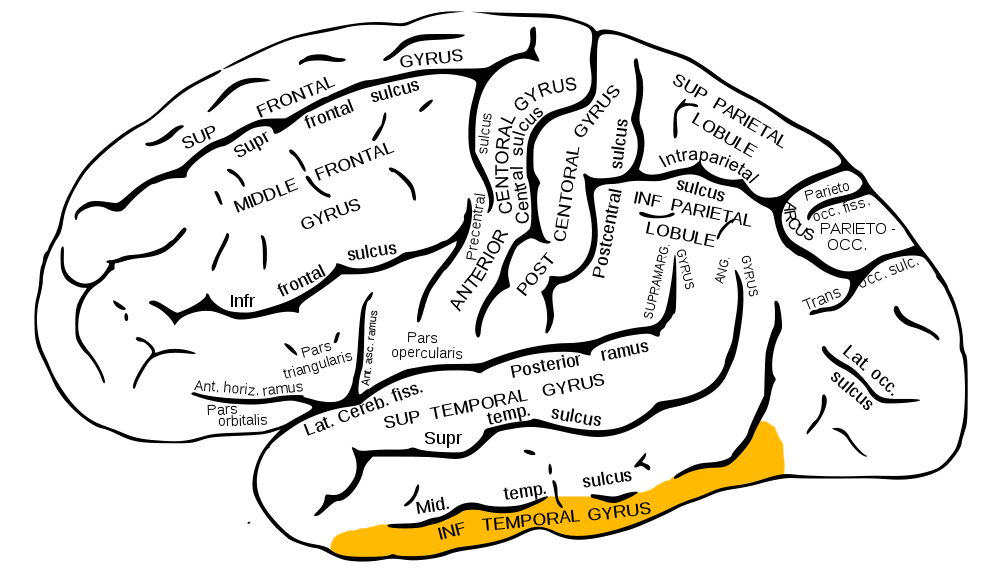

Inferior temporal cortex, or gyrus, in yellow. (Gray726/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain)

Inferior temporal cortex, or gyrus, in yellow. (Gray726/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain)

This idea of brain rewiring to process written words has been suggested before. DiCarlo and his colleagues have previously investigated the IT cortex's role in responding to objects, including faces, using functional magnetic resonance imaging.

They were also able to build on previous studies from some of the same researchers, looking at how parts of the inferior temporal cortex become highly specialised tools for recognising words once we learn how to read. However, not much is currently known about how this works at the neural level.

In the new experiments, the researchers monitored around 500 different neural sites using implanted electrodes, as the animals were shown around 2,000 words and non-words. Those data were fed into a computer model called a linear classifier, which was then trained to use the measured activity to make an intelligent guess about the nature of each string of letters.

"The efficiency of this methodology is that you don't need to train animals to do anything," says neuroscientist Rishi Rajalingham, from MIT. "What you do is just record these patterns of neural activity as you flash an image in front of the animal."

The model showed that the brain activity was indeed capable of providing information a primate would need to carry out orthographic tasks, including the interpretation of images to distinguish between words and non-words. In fact, the linear classifier could use this neural output to tell that difference with an accuracy of around 70 percent, comparable with a 2012 study of baboons trained to do the same thing.

Non-human primates, including macaques, show a lot of the same brain behaviours and ways of working as we do, and the research suggests that there's not a huge amount of difference between how these monkeys see words and how a human does.

The study also supports the idea that humans took the evolved mechanisms of the inferior temporal cortex and then repurposed them to make proper sense of words and symbols – though more research is going to be needed to know for sure.

"These results show that the IT cortex of untrained primates can serve as a precursor of orthographic processing, suggesting that the acquisition of reading in humans relies on the recycling of a brain network evolved for other visual functions," the researchers concluded.

The research has been published in Nature Communications.