Humanity has worked itself into a position where we can detect a single high-energy particle from space and wonder where in nature it came from.

Billions of people likely don't care at all about such matters, but for those who are naturally curious and are fortunate enough to have the time to indulge their curiosity, an extremely energetic neutrino detected in 2023 was a remarkable event, and may even turn out to be a historic one.

The Cubic Kilometre Neutrino Telescope, or KM3NeT, detected the extremely energetic neutrino from its location on the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea. At 220 PeV, the particle was more energetic than anything produced in our most powerful particle accelerator, the Large Hadron Collider.

The Sun emits an unceasing stream of neutrinos called solar neutrinos, but they're not very energetic.

KM3-230213A, the name given to the 100 PeV neutrino, dwarfs the Sun's neutrino output. That event was one billion times more energetic than your average solar neutrino.

There's not a long list of astrophysical phenomena that could potentially juice a neutrino like this. In fact, no currently well-understood object or process can account for it.

Explanations include pulsar-powered optical transients, gamma-ray bursts, dark matter decay, active galactic nuclei, black hole mergers, and several explanations based on different types of primordial black holes.

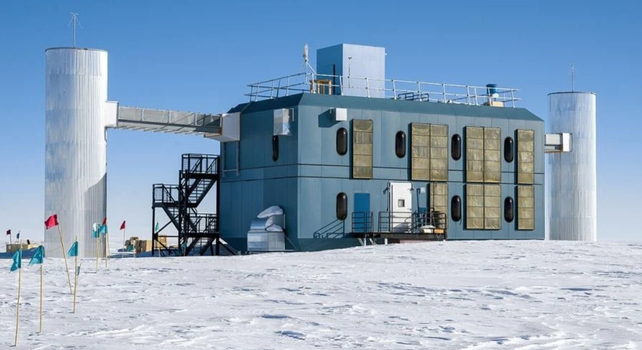

New research in Physical Review Letters has another explanation, and this one is based on primordial black holes, too. The research is titled "Explaining the PeV neutrino fluxes at KM3NeT and IceCube with quasiextremal primordial black holes," and the lead author is Michael Baker. Baker is an assistant professor of physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

"The KM3NeT experiment has recently observed a neutrino with an energy around 100 PeV, and IceCube has detected five neutrinos with energies above 1 PeV," the authors write. "While there are no known astrophysical sources, exploding primordial black holes could have produced these high-energy neutrinos."

Primordial black holes (PBHs) are entirely hypothetical. Theory says that unlike stellar-mass black holes, PBHs don't need a massive star to explode and collapse in order to form. Instead, they formed immediately after the Big Bang from dense clumps of sub-atomic matter, when the physics underlying the Universe were much different.

PBHs are much smaller than stellar mass black holes, but they're still incrediby dense, and the old adage that "nothing, not even light, can escape a black hole" still applies to them. But PBHs share something else with their cousins: Hawking Radiation.

Stephen Hawking developed the idea for Hawking Radiation (HR). It says that over time, HR reduces a black hole's mass, and that eventually a black hole will evaporate, unless it accretes more matter.

Unfortunately, HR is normally so weak that it's well below the detection threshold of even our most capable telescopes. While it's undetectable around stellar mass black holes, the situation may be different when it comes to much lighter PBHs.

"The lighter a black hole is, the hotter it should be and the more particles it will emit," said co-author Andrea Thamm, an assistant professor of physics at UMass Amherst, in a press release.

"As PBHs evaporate, they become ever lighter, and so hotter, emitting even more radiation in a runaway process until explosion. It's that Hawking radiation that our telescopes can detect."

As PBHs evaporate via runaway HR, they eventually experience a final burst. In their final second, they become extremely hot and undergo an explosive evaporation. This final act can produce high-energy neutrinos like KM3-230213A.

The researchers think that this could happen every decade, approximately, and that the explosions can produce a cornucopia of sub-atomic particles. Not just the ones we know about, like electrons and quarks, but also ones that are only hypothesized at this time, and others that may be completely unknown.

The research team thinks that KM3-230213A could be evidence for PBH evaporation. But there's one problem. The IceCube Neutrino Observatory didn't detect the event, and in fact has never detected any neutrino close to being as energetic as KM3-230213A.

If a PBH evaporation explosion happens every decade, shouldn't IceCube have detected at least one? IceCube has been observing for 20 years.

The researchers say an unusual type of PBH may be involved.

"We think that PBHs with a 'dark charge' – what we call quasi-extremal PBHs --are the missing link," says Joaquim Iguaz Juan, a postdoctoral researcher in physics at UMass Amherst and one of the paper's co-authors.

The researchers say that PBHs with a dark charge, which is basically a very heavy, hypothesized version of the electron – a "dark electron" – spend most of their time in a quasi-extremal state. In this state, the PBH is almost at its maximum possible charge-to-mass ratio.

Related: Record-Breaking Neutrino From Deep Space Spotted by Undersea Telescope

IceCube and KM3NeT are tuned to different energies. IceCube is limited to 10 PeV, and that can explain why it never detected KM3-230213A.

For Baker, the added complexity of dark charge PBH adds more veracity to their explanation.

"Our dark-charge model is more complex, which means it may provide a more accurate model of reality," says Baker. "What's so cool is to see that our model can explain this otherwise unexplainable phenomenon."

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.