There was a big stir when reports emerged that the Curiosity rover had detected methane on Mars. But there was a problem: it could not be ruled out that its sensors were wiggy, or something was misinterpreted.

Now it seems we can put that concern to rest - because an independent source has also detected methane on Mars.

On 16 June 2013, a day before Curiosity detected methane in the same region, the European Space Agency's Mars Express mission, in orbit around the Red Planet, caught a whiff of the stuff near the Gale Crater - the region explored by Curiosity.

Other instruments have detected methane on Mars. But this is the first time two separate pieces of equipment have detected methane (CH4) in the same region at the same time.

"Despite various detections reported by separate groups and different experiments, and although plausible mechanisms have been proposed to explain the observed abundance, variability and lifetime of methane in the current Martian atmosphere, the methane debate still splits the Mars community," planetary scientist Marco Giuranna of the Italian Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica told ScienceAlert.

"Prior to our study, methane detections on Mars were not confirmed by independent observations. This latest finding constitutes the first independent confirmation of a methane detection."

It makes previous detections more difficult to explain away as a glitch in the data, or poor spectral resolution, or even - as has been argued - methane that was inside Curiosity to start with.

Nope. That methane is definitely Martian.

And it could be a truly big deal. Here on Earth, we have a fair amount of the stuff - about 1,800 parts per billion by volume (ppbv) in the atmosphere as of 2011, of which 90 to 95 percent is generated by living or deceased creatures.

There are geological processes that can generate methane abiotically. On gas and ice giants such as Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, plenty of methane is produced via chemical processes.

Pluto has methane ice. Saturn's moon Titan has lakes of liquid methane. The stuff isn't exactly rare in the Solar System.

On Mars, too, the global concentration is minuscule compared to Earth's - it appears in bursts, with a global average of just 10 ppbv. But figuring out where the Martian methane came from, and how, will tell us something new and exciting about the Red Planet - even if that source is not microbes.

The Mars Express orbiter did actually detect methane once before, in 2004, using the Planetary Fourier Spectrometer (PFS) instrument. It's this instrument that made the 2013 detection, too, but with new observation and analysis techniques that increase confidence in the results.

"Due to its weak absorption, relatively low abundance, and high spatial and temporal variability, quantitative analyses of CH4 with PFS require special attention to the way the spectra are collected, handled, and analysed," Giuranna said.

He added that the team developed a new approach to selecting and retrieving data from the PFS, analysing it with methods that improve accuracy and "reduce statistical uncertainties".

(Giuranna et al., Nature Geoscience, 2019)

(Giuranna et al., Nature Geoscience, 2019)

This required a lot of work from the ground up - which is why the result is only being released now, nearly six years after the detection. But that painstaking work has paid off, because it's narrowed where on Mars we can look for methane being released.

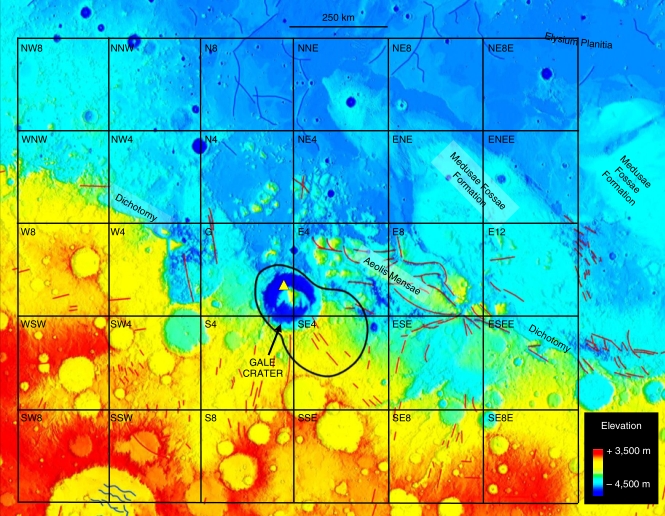

According to the researchers, transient events in a fault region near the Gale Crater are the most likely place of methane release. That could also explain why it disappears and reappears so peculiarly.

"The fretted terrain of Aeolis Mensae is in contact with the region of Medusae Fossae Formation (MFF) and in close proximity to locations where the MFF has been proposed to contain shallow bulk ice," Giuranna told ScienceAlert.

"Since permafrost is one of the best seals for methane, it is possible that bulk ice in the MFF may trap and seal subsurface methane.

"That methane could be released episodically along faults that break through the permafrost due to partial melting of ice, gas pressure build-up induced by gas accumulation during migration, or stresses due to planetary adjustments or local meteorite impact."

We won't know until we can go look - but now we know that further investigation would absolutely be worthwhile.

Meanwhile, the search for methane is ongoing. The PFS instrument continues to monitor the Martian atmosphere, and its entire data backlog will be reanalysed using the team's new techniques.

The research has been published in Nature Geoscience.