For only the second time ever in medical literature, a human has contracted a rare infection of Thelazia gulosa – an ocular parasite that turns the eyes into a breeding ground for squiggling worms.

While this is only the second documented case in humans, given both known infections took place within two years of one another, scientists say we could be looking at a newly emerging zoonotic disease type in the US.

In a startling case report documenting the second infection, scientists from the CDC's parasitic diseases division tell the story of a 68-year-old patient from Nebraska who spent her winters in the warmer climate of California's Carmel Valley.

During these sojourns, she enjoyed trail running, which is what she was doing one day in early February 2018, when something unpleasant happened. As she rounded a corner on a steep trail, she ran directly into a swarm of small flies.

"She recalls swatting the flies from her face and spitting them out of her mouth," the researchers explain in their case report.

The strange episode didn't end there, though; in fact, it may have only just gotten started.

The following month, the woman noted irritation in her right eye, and the cause of the discomfort didn't take long to reveal itself.

While washing her eye with tap water, she flushed out a transparent, motile roundworm measuring about half an inch in length (about 1.25 cm).

It wasn't alone. Further inspection revealed another worm in her eye (which she was also able to extract), and the next day she visited an ophthalmologist, who fished out a third, and prescribed her an antibiotic ointment to treat any bacterial infections.

A couple of weeks later, she returned home to Nebraska, still feeling continued irritation and a "foreign body sensation" in both eyes. Another ophthalmologist examination diagnosed her with mild bilateral papillary conjunctivitis, but wasn't able to detect any additional nematodes.

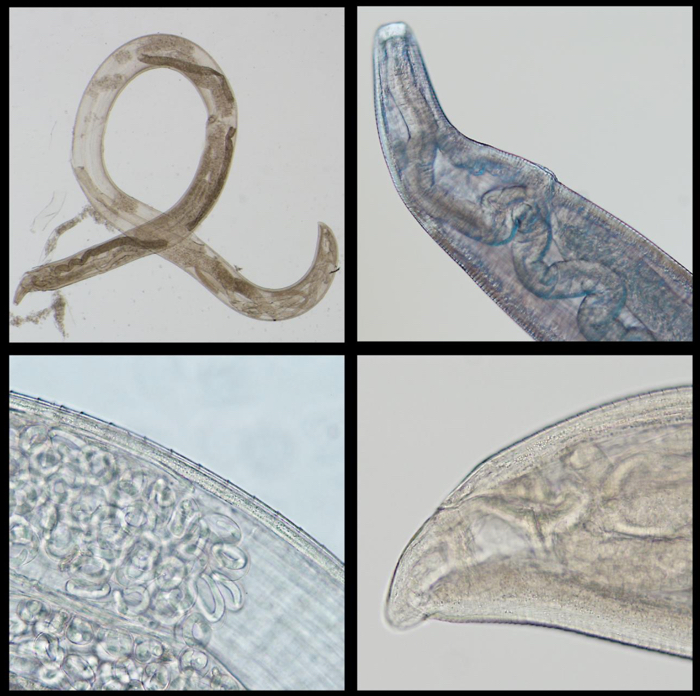

T. gulosa female worm, revealing ovaries containing spirurid eggs and larvae at bottom-left. (Bradbury et al., Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2019)

T. gulosa female worm, revealing ovaries containing spirurid eggs and larvae at bottom-left. (Bradbury et al., Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2019)

Nonetheless, the patient found and removed a fourth worm from her eye shortly afterward, and luckily her conjunctivitis subsequently resolved.

That fourth worm was the last ever found in the woman's eyes, and for that she might consider herself lucky. At least, in the only previous human case of the same infection, 14 worms were discovered lurking in the 26-year-old patient's eyes.

Analysis of one of a nematode sample collected from the Nebraska patient confirmed her case was the second known instance of the parasitic T. gulosa infection (aka the cattle eyeworm), and revealed a literal litter of surprises besides.

"The worm was identified as an adult female T. gulosa," the authors write.

"Importantly, eggs containing developed larvae were observed in utero, indicating that humans are suitable hosts for the reproduction of T. gulosa."

Other kinds of Thelazia species have been known to infect humans before in the US, causing the disease Thelaziasis, although documented cases are rare.

If you do have these worms squiggling around in your eye, though, you don't want to delay in getting them out of there, the researchers warn.

"In long-term untreated infections, chronic irritation caused by the passage of adult worms over the cornea may result in keratitis, loss of visual acuity, or even blindness," the team explains.

"In reported cases where the infesting nematodes have been removed from the eye within one to two months of first observation, the associated conjunctivitis has resolved and no long term clinical effects have been observed."

In cases like these, it's relatively impossible to determine for sure just how a patient got infected, but in both the human cases, the probable cause is known.

Thelazia eyeworms are transmitted between animals by species of flies. Most commonly, in the case of T. gulosa, they are known to carry the infection to cattle.

As such, if you're in the vicinity of cattle (like the farm-visiting patient in the first case, who practised horse-riding) or have the misfortune of running face-first into a swarm of flies in a rural area (like the second patient), you just might stand a chance of contracting the parasite.

How significant is the threat? From what we know so far, the incidence of these infections in humans remains extremely rare, although the temporal coincidence of these two cases could be significant.

In cattle, T. gulosa infections have been identified in several US states, as well as Canada, Europe, Asia, and Australia, but testing for the parasite in these regions may not be considered a strict priority.

"The reasons for this species only now infecting humans remain obscure," the authors explain.

"Monitoring of thelaziasis in cattle does not occur, and therefore it cannot be determined if there is an increasing prevalence of T. gulosa infections among domestic cattle which is resulting in zoonotic spillover events into humans and other unusual hosts. Renewed surveillance studies on domestic and wild ruminants would assist in better elucidating the situation in those hosts and would indicate what regions of the United States further human infections might occur in."

The findings are reported in Clinical Infectious Diseases.