A new study has concluded over five decades of work to find, identify, and classify the mineral that makes up 38 percent of the Earth.

The International Mineralogical Association states that minerals can only be named and classified once they've been analysed in their natural state. The problem with this and the mineral that makes up a third of our planet is that its natural state lies within the Earth's lower mantle - a rocky layer that stretches from 650 to 2,900 kilometres below the surface.

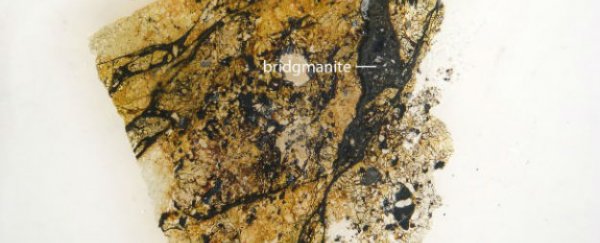

It appeared virtually impossible to classify this nameless mineral - a super-dense version of magnesium iron silicate - because when a sample is extracted from the lower mantle, its internal structure would be destroyed as it made the long journey to the surface. So scientists led by Oliver Tschauner from the University of Nevada in the US decided to analyse a mineral conglomerate also known to undergo extremely high pressures - "collisions between asteroids in space, such as the one that created the Australian meteorite hundreds of millions of years ago", says Sid Perkins at Science Magazine.

While still in space, the meteorite had experienced incredible temperatures of around 2,100 degrees Celsius, and pressures akin to what you'd find hundreds of kilometres into the Earth - about 240,000 times sea-level air pressure, Perkins reports. And it happened to contain microscopic pieces of the nameless mantle mineral.

Working with a kind of particle accelerator that emits very strong x-rays, called a synchotron, the team was able to reconstruct its crystalline structure and figure out what the mineral itself is composed of. Thanks to the time it spent in the icy temperatures of space, the atoms inside the mineral had been frozen in place, and its structure remained unchanged, allowing them to analyse it as if it like it was sitting inside the Earth's mantle.

Now that it's been classified, the team has called the nameless mineral bridgmanite, after 1946 Nobel Prize winner in Physics, Percy Bridgman, who was the first to figure out how to analyse minerals that have experienced extreme pressures.

"Previous estimates suggest that 70 percent of Earth's lower mantle - which falls between depths of 660 and 2900 kilometres - is bridgmanite, the researchers say," Perkins writes at Science Magazine. "That means the new mineral accounts for a whopping 38 percent of Earth's entire volume."

The results have been published in the latest edition of the journal Science.

Source: Science Magazine