The dark bowels of a limestone cave on Muna Island, off the coast of Sulawesi in Indonesia, just yielded an ancient secret.

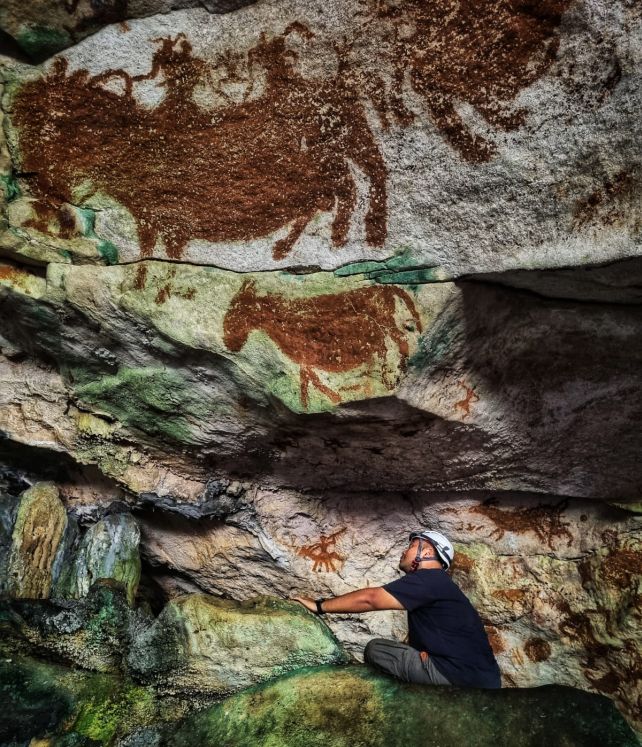

There, a team of archaeologists has discovered human-made rock art older than any other reliably dated example, with a minimum age of 67,800 years ago. The eerie hand stencils with their pointed fingers represent an important piece of the puzzle about early human migration across the region, tens of thousands of years ago.

"What we are seeing in Indonesia is probably not a series of isolated surprises, but the gradual revealing of a much deeper and older cultural tradition that has simply been invisible to us until recently," archaeologist Maxime Aubert of Griffith University in Australia, who co-led the research, told ScienceAlert.

"The amount and great age of rock art found there show that this was not a marginal or temporary place. Instead, it was a cultural heartland where early humans lived, travelled, and expressed ideas through art for tens of thousands of years."

Related: Cave Painting of a Pig Hunt Could Be The Oldest Story Ever Recorded

In recent years, both Sulawesi and the Indonesian portion of Borneo have emerged as unexpectedly important sites for understanding early human creativity and migration. In many cases, cave paintings were discovered decades ago, but researchers lacked reliable methods to determine their age.

Thanks to advances in dating techniques, scientists now know that some of these artworks are far older than previously thought, with minimum ages exceeding 40,000 years and stretching beyond 51,000 years.

"Each time we apply these methods in new areas, the ages turn out to be much older than expected," Aubert said. "That tells us the problem was not that early humans were suddenly making art in one place, but that we have been looking in the wrong places, or not looking carefully enough."

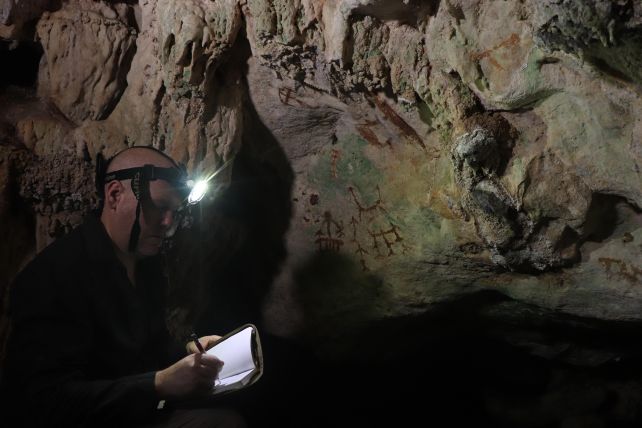

This most recent finding was made in Liang Metanduno, a cave long known to contain ancient rock art. Aubert and his colleagues wanted to determine where the creations in this cave fit into the timeline of ancient art in the Indonesian archipelago.

If archaeologists are lucky, over a timespan of thousands of years, a thin layer of calcite is deposited over the art, precipitated from water running over the surface of the rock. This water often contains a small amount of uranium, which is soluble in water. Over time, uranium decays into thorium, which is not water-soluble.

Because the rate at which uranium decays into thorium is precisely known, scientists can look at the ratios of uranium and thorium in samples of the coating to determine how old it is.

That means it is not the paint itself that has been dated to 67,800 years ago, but the mineral crust that formed on top of it. The art beneath must therefore be at least that old.

And, combined with previous evidence, this suggests that much of the rock art in the region is potentially far older than previously estimated, which in turn would change how we understand Sulawesi – a key stopping point for early human migration to Australia.

"Art may have become especially important as populations grew and groups interacted more often," Aubert said.

"One way to think about this is through modern examples. Traffic lights are needed in large cities, but not in small villages. In a similar way, art, symbols, and shared images may have helped people communicate identity, belonging, and shared meaning as social networks became larger and more complex."

For archaeologists, this kind of symbolic behavior matters because of when and where it appears. The newly dated art sits along a proposed northern migration route that early modern humans are thought to have taken as they moved through Island Southeast Asia toward Sahul, the Ice Age landmass that once joined Australia and New Guinea.

Finding evidence of complex artistic traditions along this corridor helps fill a long-standing gap between early sites in mainland Asia and the earliest traces of people in Australia, and suggests that humans could have arrived on Sahul by as early as 65,000 years ago.

It also throws open many more exciting questions, such as how much more rock art of this era remains to be discovered in the surrounding area, how symbolic traditions traveled and spread, and whether there are even earlier chapters of this story yet to be discovered.

"What excites us most is that this art shows early people in Southeast Asia were already expressing ideas, identity, and meaning through images tens of thousands of years ago. These were not isolated experiments. They were part of a long-lasting cultural tradition," Aubert said.

"For us, this discovery is not the end of the story. It is an invitation to keep looking."

The research has been published in Nature.