Aspen forest is reclaiming the skyline of Yellowstone National Park after decades of controversy over efforts to return wolves to the ecosystem.

The successful growth of a new Aspen overstory for the first time in 80 years validates the efforts of conservationists who have fought to protect and restore predators for their role in keeping the park's ecosystems self-sustaining.

Critical links between populations of gray wolves (Canis lupus) and quaking aspen trees (Populus tremuloides) weren't obvious when the canine predator was eradicated from the park in the 1920s; a result of government control programs that encouraged people to hunt predators like wolves, coyotes and cougars.

Among the wolves' prey are the elk Cervus canadensis that gnaw at aspen and cottonwood saplings and trample exposed soils with their hooves. Controlled by natural predators, the elk's numbers – and therefore damage from chewing and trotting – is limited. But in the absence of wolves, their population swells and their taste for saplings leads to overgrazing.

Related: Wolves in Scotland Could Help Reduce Carbon in The Sky. Here's How.

As early as 1934, a team of scientists noted "the range was in deplorable condition when we first saw it [in 1929], and its deterioration has been progressing steadily since then."

As old aspen stands died, there were no new trees to take their place. Species that rely on mature aspen, like beavers and cavity-nesting birds, were left stranded. Without wolves, the ecosystem was falling apart.

It took decades of petitioning, but by 1995, wolves were reintroduced to the park. After finding their feet, a population introduced from Jasper National Park in Canada settled into their role of hunting elk and, indirectly, protecting young trees. With few or no remaining overstory trees, many of today's aspen stands are expected to die without saplings.

Now, after thirty years, these wolves have raised a new generation of aspen trees, the first to form an overstory in the park since the 1940s. These stands of trees, which have now officially survived past their fragile sapling state, are testament to the success of the wolf reintroduction program, and the importance of top predators in maintaining a healthy ecosystem.

"The reintroduction of large carnivores has initiated a recovery process that had been shut down for decades," says Oregon State University ecologist Luke Painter, who led the study.

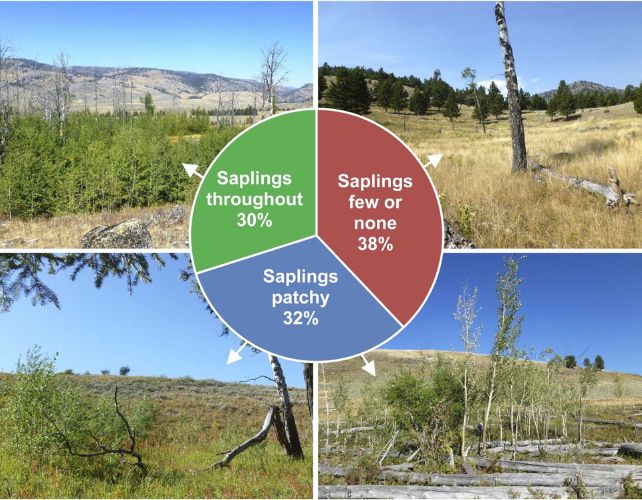

"About a third of the 87 aspen stands we examined had large numbers of tall saplings throughout, a remarkable change from the 1990s when surveys found none at all."

Among the aspens, Painter and team define in their paper, saplings are shorter than 2 meters (around 6.6 feet), or those with trunks slimmer than a 5 centimeter diameter at breast height (dbh); trees have trunks with a dbh above 5 centimeters.

Of all the stands they sampled, 43 percent contained new, small trees that had surpassed that diameter cutoff. And since 1998, the density of saplings over 2 meters tall has increased 152-fold, which means there are now many more chances for long-term survival.

To ensure that this effect was due to the return of wolves to the park, and not other factors like climate, the team also measured the rates at which the elk ate the trees. Aspen stands with many tall saplings, they found, had much lower browsing rates, while other stands that continue to be chewed back by elk were not producing these new forest recruits.

This, Painter says, is a sure sign the trees' recovery is part of a top-down trophic cascade.

"This is a remarkable case of ecological restoration," Painter says. "Wolf reintroduction is yielding long-term ecological changes contributing to increased biodiversity and habitat diversity."

This research was published in Forest Ecology and Management.