Every single human on this planet is as distinct as a snowflake; a combination of traits and genes and microbes that, as far as we can tell, is not replicated exactly in any other single human.

One trait that is unique to each individual is the breath that sustains us. Each person has an idiosyncratic pattern to the constant inhale-exhale that counts out our hours, days, and years on this planet.

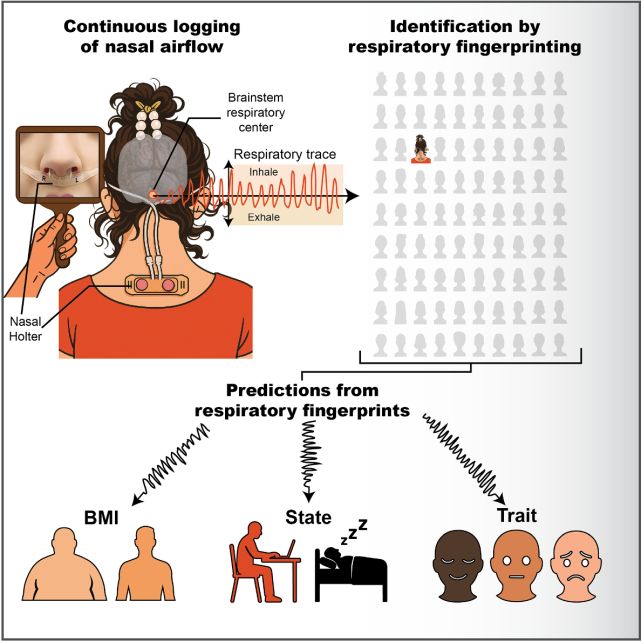

That's what a team of scientists discovered after fitting people with a wearable device that monitored their nasal breathing. An analysis of the data revealed patterns that were detailed enough for the researchers to identify individuals with an accuracy of 96.8 percent.

This 'respiratory fingerprint', says a team led by brain scientist Timna Soroka of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, could promote new ways to understand and treat physical and mental ailments.

"You would think that breathing has been measured and analyzed in every way," says neuroscientist Noam Sobel of the Weizmann Institute of Science. "Yet we stumbled upon a completely new way to look at respiration. We consider this as a brain readout."

We can take breathing somewhat for granted, but it's governed by a complex and extensive brain network that largely automates the process, permitting for conscious control by the individual when circumstances require – such as holding one's breath when jumping into water, for instance.

Soroka, Sobel, and their colleagues at the Weizmann Olfaction Research Group have been investigating the way the brain processes scent during inhalation. During this research, they made the very small leap towards studying the concept of a breath-print.

"The idea of using an individual's breathing pattern as a unique signature has been discussed for decades within the respiratory science community. You can easily see each person's uniqueness when you measure different people," Soroka told ScienceAlert.

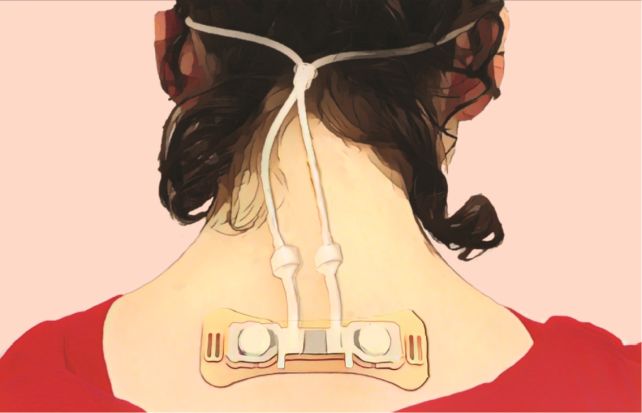

"However, there was no convenient way to measure it until now. The development of a tiny wearable device capable of recording over extended periods allowed us to measure 100 participants over 24 hours. This, in turn, enabled us to present the concept in a much more compelling way."

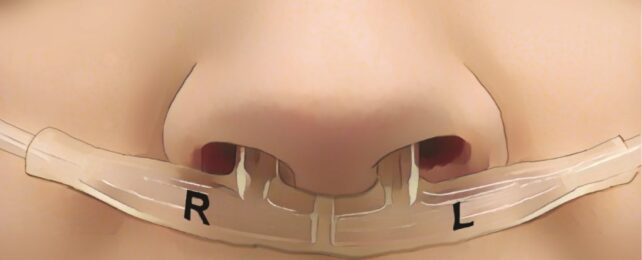

The researchers developed a device that precisely monitors and logs the airflow through each nostril of the wearer. Then, they tasked 97 study participants with wearing the device for up to 24 hours. From just one hour of recording, the researchers achieved an accurate identification rate of 43 percent, Soroka said. This accuracy skyrocketed at 24 hours.

The resulting breath log was then analyzed using a protocol known as BreathMetrics, which examines 24 parameters of the individual's nasal respiration.

Since respiration is usually only measured for short periods of time – around 20 minutes or so – the resulting dataset was far more comprehensive than usually seen, giving a much more comprehensive view of each individual's respiration, from rest to exertion.

"We expected to be able to identify individuals," Soroka said, "but not that it would be so strong."

The researchers did not just find that an individual can be confidently identified based on their breathing pattern; the results also revealed what those breathing patterns can indicate about a person.

There's the usual gamut of activities. A person at rest will have a distinct breathing pattern as opposed to someone out on a constitutional jog, for instance. The researchers also found that a person's breathing correlates with their BMI.

The study participants were tasked with filling out questionnaires about their mental health. Those participants with self-reported anxiety issues generally had shorter inhales and more variability in the pauses between their breaths while sleeping.

While not the purpose of the study, this indicates an avenue for further investigation. People undergoing significant stress or panic are given breathing exercises to help mitigate their symptoms. Perhaps working on conscious breathing could be more helpful than we thought.

The next step, however, will be how this research might be applied to diagnostics, Soroka said.

"We can learn how specific breathing patterns may predict various diseases," she explained. "But of course, in the future we will examine whether we can also treat disease by modifying respiratory patterns."

The research has been published in Current Biology.