Motes of plastic less than a micrometer across could outnumber larger fragments and particles floating through the oceans to a shocking extent, a new study has discovered.

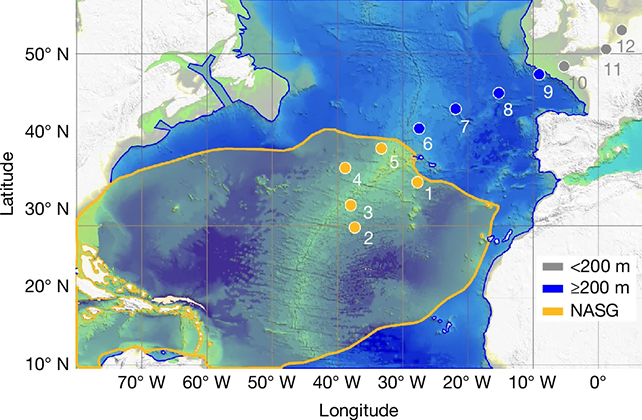

Led by a team from Utrecht University in the Netherlands, the study is based on samples taken at varying depths from 12 sites across the North Atlantic. High-resolution imaging scans and chemical filtering were used to find nanoplastics in the samples, which can be tricky to spot due to their very small size (just a fraction of the thickness of a human hair).

The analysis was clear: the ocean is swimming with nanoplastics, perhaps some 27 million tonnes when extrapolated across the whole of the North Atlantic Ocean. That's almost a tenth of the entire volume of trash thrown away in the US each year.

"This estimate shows that there is more plastic in the form of nanoparticles floating in this part of the ocean than there is in larger micro or macroplastics floating in the Atlantic or even all the world's oceans," says biogeochemist Helge Niemann, from Utrecht University.

Related: 7,000 Microplastics Studies Show We Have One Really Big Problem

The findings illustrate the sheer scale of the ecological problem posed by waste plastics.

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polystyrene (PS), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastics were all found, commonly used in plastic bottles, cups, and films.

Some plastics were largely missing though: polyethylene and polypropylene, which are ubiquitous in the environment. The researchers think this might be because organic particles are masking their presence, or the analysis techniques in use aren't currently sensitive enough to pick these types of plastic up.

Nanoplastics were found at all of the surveyed depths, but were particularly concentrated around the coasts (from rivers and runoff) and in the subtropical gyre, a place of swirling circular currents that's well known for trapping plastics which proceed to break up into ever-finer pieces.

What's not clear is the precise extent to which plastics harm marine ecosystems, and in turn species that rely upon them. Including our own. Super-small nanoplastics can interact with water, sediment, and other organisms in ways larger microplastics can't.

"Nanoplastic and nanoparticles are so small that the physical laws governing larger particles often no longer apply," says chemist Dušan Materić, from the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research in Germany.

Next, the researchers want to see more ocean areas sampled, with surveys scanned for more types of plastic – something that should be possible by adapting the techniques used in this study. It's also important to look for nanoplastics at different stages of degradation, based on how long they've been in the water.

Plastic pollution at this scale is going to be very difficult to eliminate, which is why the researchers are calling for more to be done to stop plastics from entering the environment in the first place.

"Only a couple of years ago, there was still debate over whether nanoplastic even exists," says Materić. "Many scholars continue to believe that nanoplastics are thermodynamically unlikely to persist in nature, as their formation requires high energy."

"Our findings show that, by mass, the amount of nanoplastic is comparable to what was previously found for macro and microplastic – at least in this ocean system."

The research has been published in Nature.