Octopuses are mostly made up of sucker-studded arms, each one packed with muscles and nerves that enable them to engage with their environment in ways no other invertebrate has mastered.

But how octopuses negotiate their sprawling mass of semi-autonomous limbs remains a mystery. A new study by biologists at Florida Atlantic University and the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole in the US reveals there is some method to the madness.

While each arm has a mind of its own, it turns out they do tend to use specific arms for specific tasks.

Related: Octopuses Fall For The Classic Fake Arm Trick – Just Like We Do

This kind of arm favoring is well-known in primates, rodents, and fish, but there's been very little research as to whether it's the case for octopuses.

To get a better grip on this phenomenon, a team led by Chelsea Bennice, a marine biologist and octopus specialist from Florida Atlantic University, pointed underwater cameras at 25 wild octopuses (either Octopus vulgaris, O. insularis, or O. americanus).

They inhabited a range of environments in the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, all in depths less than 10 meters (33 feet), where light can easily bounce from their colorful chromatophores into the camera lens.

During filming, which took place between 2007 and 2015, some of the octopuses strode across shell rubble; some lurked in seagrass beds; some shimmied through live coral reefs; and some traversed multiple terrains. From this broad sample of wild octopuses doing their thing in nature emerged a clear picture of what their arms are capable of.

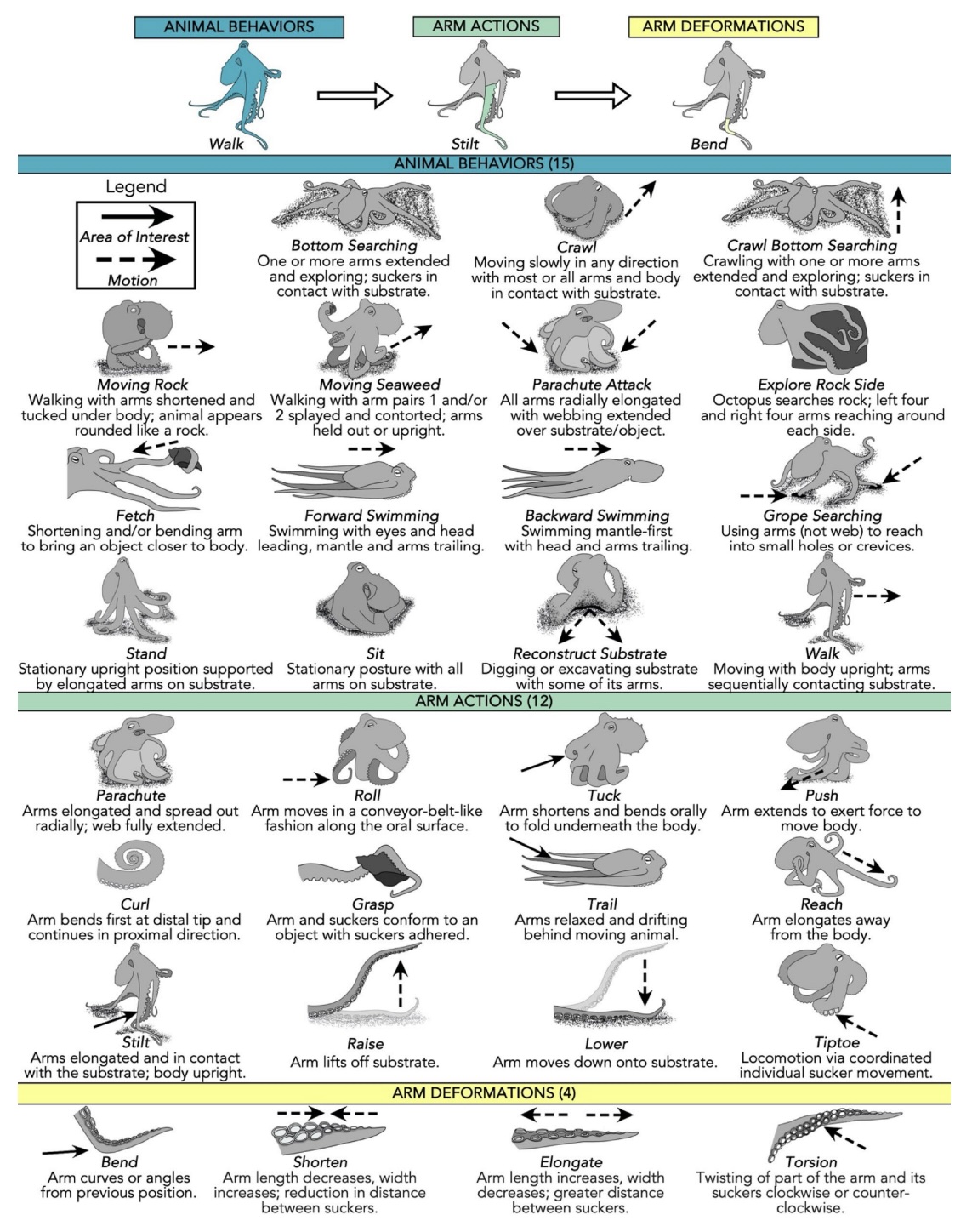

A total of 3,907 different instances of arm action revealed that octopuses are well and truly dexterous in every direction: any octopus arm is up for any task.

And, as you can see, the researcher's catalogue of these tasks was rather extensive:

That said, the octopuses did tend to use their front four arms (those extending forward from their body) more frequently, accounting for 64 percent of actions, than the four rear-facing arms, which were called on only 36 percent of the time.

Octopuses, it turns out, are more likely to use their front arms to explore their environment, reaching into the future and grabbing at what lies therein.

Meanwhile, their rear arms are more often involved in locomotion, by either rolling the octopus across the seafloor in a conveyor belt-like action, or by lifting the body on 'stilts' by extending the arms straight down to the seafloor.

It's a bit like how we tend to use our hands, rather than our feet, to manipulate the world around us – the difference is that for octopuses, limbs do not appear to be physically specialized for these different tasks. If an octopus could learn to write its name, it could probably do so just as easily with any arm, although it's perhaps more likely to use one of the front four.

And, unlike humans, octopuses don't have a preference for using their left or right limb, it appears. They're basically ambidextrous. But when a task called for a pair of limbs, the octopuses tended to coordinate the corresponding arm on the left and right side to form the pair, betraying their bilateral symmetry.

"All eight arms seem capable of nearly all actions and deformations, indicating adaptability and redundancy among the arms," Bennice and her team write.

"The combination of deformations and arm actions implemented to achieve complex behaviors illustrates extreme arm flexibility and coordination during a wide range of arm functions."

This research was published in Scientific Reports.